9 Things I Learned About Gaming With Disabilities from the Ablegamers Foundation and My Son

|

Visiting Katsucon two years ago, I was introduced to the Ablegamers Foundation, a group dedicated to bring gaming to people with disabilities through custom controllers and interfaces. Thanks to my son Connor, I immediately felt a personal connection to their mission, and hoped that in the future, there might be something they could do to make video games more accessible to him. Later, an invite appeared in my e-mail inbox, letting me know about Ablegamer’s open house on July 5th, where they would open their doors to gamers with disabilities, help evaluate them for custom interfaces, and even go so far as to help them apply for grants to pay for what could be potentially expensive equipment. I decided this would be the perfect time to take Connor out to their headquarters near Washington D.C. and see what options were available to make his gaming experience more fun and rewarding.

As I begin this article, I’m observing my boys at their My Gym class. I’m uncharacteristically nervous; it’s Connor’s first day in the class. At eight years old, he stands almost a foot taller than the rest of the class, and it’s obvious that he’s as nervous as I am, if not more so. He hates being the center of attention in front of strangers, especially when there is physical activity involved, but his confidence is boosted a bit by his little brother being here, most likely because he doesn’t want to be outdone.

The difference, aside from age and height, between Connor and the rest of the children is that Connor was diagnosed with mild to moderate Cerebral Palsy due to a birth injury. The average person would just think that Connor is just uncoordinated or accident prone, but in truth, damage to his brain has diminished his fine motor skills significantly. Handwriting is a challenge, sports nearly impossible, and when he is tired or distracted, his legs can just randomly go out from under him. Thankfully his condition is far better than what was initially expected, as doctors were quick to tell his mother and me not to expect him to walk or talk, if he even survived the initial trauma. It’s a huge change in perspective for a father who, for the nine months of pregnancy, had only visions of success in his mind for his child.

Connor, while still having difficulty, had far exceeded the expectations initially laid out for him. He’s a straight-A student, an enormously caring big brother, and an uber-nerd in training. One aspect of nerd culture that he adores is video games, a place where, for the most part, his physical limitations are negated. His decade-older stepbrother had him “fragging newbs” online in Call of Duty online at age four, and he’s an absolute beast at all things Mario Kart. The difficulty he has in gaming lies in his fine motor skills. Put a Mario Kart steering wheel in his hands and he can dominate, but games requiring a more precise touch like Skylanders Swap Force can cause immeasurable amounts of frustration, both for Connor and for his younger brother who is likely his co-op partner. The Ablegamers open house was the perfect opportunity to see if there was something we could do to take the frustration out of something that should be fun. It was an amazing, rewarding and emotional experience for both Connor and myself. Here are nine things I learned about gaming with disabilities, the Ablegamers Foundation, and my son.

1. Accessibility Isn’t Cheap.

|

According to Chief Operating Officer Steve Spohn, money is the biggest obstacle to the organization’s mission. While corporate sponsors like Harmonix, Rockstar and others contribute, the majority of their supporters are ordinary gamers. That financial support is used for research and development, outreach programs, and awarding grants to disabled gamers in need. In the past year alone, they’ve been able to award grants to around forty-five gamers for specialized controllers that cost between $300 and $3000 dollars apiece.

While their current fundraising campaign aims to take their program on the road, there are still three hundred gamers on a list waiting for their grants to be fulfilled. With more people being added to the queue daily and the number of disabled gamers on the rise, the challenge facing Ablegamers is certainly one of ever growing expenses, but to a newly empowered player and his or her family, the benefits are certainly worth their weight in gold-pressed latinum.

2. The Industry Still Considers the Disabled a Niche.

|

According to Steve, there are thirty three million gamers in the US who have some form of disability. With the average age of gamers going up, it’s a number that will be increasing exponentially. That being said, while independent developers like Bohemia Interactive (Day Z) are including accessibility options like TrackIR (head tracking view control), major AAA developers are not addressing accessibility concerns. Steve believes that this is due to developers still considering disabled gamers a niche market, regardless of the ever growing numbers. For the foreseeable future, disabled gamers will remain a perceived niche, just like women gamers, gamers over the age of thirty-five, and people who don’t like Grand Theft Auto.

3. The QuadStick Is Astounding.

|

My introduction to disabled gaming was an article in Nintendo Power during the late ’80s. The concept of controlling Mario with just head motions and breathing through a straw was almost impossible to fathom. More than twenty years and twenty-seven thousand dollars raised on Kickstarter later, the successor, the QuadStick was born.

While able to interface with a PC, PS3 or Android, this QuadStick looks almost identical to its predecessor. The similarities end at appearance, however; instead of being able to emulate a simple NES controller, the QuadStick has all of the capabilities of a PS3 controller, and can be combined with voice recognition software for an even easier interface. Watching the video above makes the whole process look quite complicated, but as the player in the video states, he was able to complete four games in the Call of Duty series without having been able to play them before. Quite an accomplishment, and a testament to the abilities of the controller and the tenacity of the player…I for one haven’t finished a Call of Duty campaign since number two.

4. They’re Taking This Show on the Road.

At first glance, the best word to describe the Ablegamers headquarters located just outside of Washington D.C. would be modest, as in the small office is about the size of a modest apartment, tucked away in a business park. While an organization like this doesn’t need a Park Avenue penthouse, the nature of their business requires mobility. Since so many of the people they could potentially help live full-time in hospitals, facilities and veteran centers, making the trek to the West Virginia headquarters or to one of the conventions Ablegamers attends would be a daunting task. Hence their current project: “Driving Home Accessibility”.

The project would involve purchasing and retrofitting a van to become a completely mobile gaming laboratory, in which gamers with disabilities could explore the options available to them and speak with experts ready to assist them. It’s not a cheap project; it will take $200,000 to procure and outfit a van for their needs, though if the funding allows, a cross-country tour will follow, with Ablegamers visiting major cities to provide free consultations. It would be like the Blues Brothers without the blues, or the brothers for that matter, or police chases…we hope.

5. Next Gen Gaming Equals Next Gen Problems.

As the technology advanced, so do the difficulties in developing new accessible controllers. Console makers are notoriously strict with allowing hardware development from third parties. Concerns about macro-ability seems to be a key issue; manufacturers don’t want anyone using a specialized controller, including those made for disabled players, to have an unfair advantage or the ability to program cheats. According to Steve, some PC MMO developers even went so far as to ban some of the controllers used by disabled gamers for fear of tipping the in-game balance.

Sadly, it seems that accessibility is not necessarily on the minds of hardware developers. The Wii U, for example, seems like a device that, despite its easy interface, has walled itself off from gamers with the most severe of disabilities. Gamers without the use of their hands will simply not be able to use a Wii U without hardware and software modification that frankly doesn’t exist, and according to Quasimoto Interactive, makers of the Axis series of accessible controllers, will likely never exist.

Microsoft doesn’t seem to hinder development in accessibility technologies. A “gentleman’s agreement” exists that allows companies to develop these technologies for Xbox platforms without expensive license fees, so long as said companies don’t rake in profits from their developments. While not ready for prime time, Quasimoto has had success in adapting their Axis controller to work on the Xbox One. Sony, on the other hand, has become more difficult to develop hardware for in general; almost a year after launch, no third-party controller exists for the PlayStation 4. But according to Steve it’s not about gaining an advantage: “We just want to be able to die like everyone else.” I’ll presume he meant that virtually.

6. Accommodation is Not All About Hardware.

It’s hard to imagine a time where even that most basic accommodation – subtitles – wasn’t something included in a game. Sadly, though, there was a time when subtitles were an additional cost or time expenditure that was expendable. While the ability to read the spoken text is something we’ve grown to expect, very few companies are going out of the way to include software-based accessibility options like colorblind mode.

Ubisoft became the bane of E3 this year for choosing not to include a female protagonist in the upcoming Assassin’s Creed Unity, citing a simple lack of time, and sadly, that lack of time is often the response groups like Ablegamers get when they ask for software accommodations, particularly from larger studios who feel the need to rehash old ideas and come up with a sequel for their top selling titles each year.

7. Helping Those Who Don’t Know It.

|

When asked about the greatest accomplishment Ablegamers has had, Steve told me he gets the greatest satisfaction from helping those who don’t realize it. By spreading the word, reminding companies about the needs of the disabled, they’ve helped more than just those who have come to them. Their work is seen every time a company includes support for specialized controllers, build in features like colorblind mode, or simply just think of what they can do to reach the disabled audience. They are the charity that, according to Steve, “wants to be put out of business.”

8. Anyone Can Help.

|

The easiest way someone can get involved is by simply donating money, but there is so much more we can do. In the next few weeks, the Ablegamers “Driving Home Accessibility” campaign will go into full swing, with a 72-hour Minecraft “Mineathon” the last weekend of July, and a 72-hour game-a-thon September 12th through 14th, where people can form their own gaming teams to play and stream, raising money for the charity. So when my wife finishes her last shift of the weekend on September 15th, she’ll be wondering why our house is covered in Red Bull cans, empty Doritos bags, why my kids eyeballs are bleeding and when was the last time I showered, because I’m doing my part for charity! Anyone else thinking Team Topless Robot?

9. Connor.

|

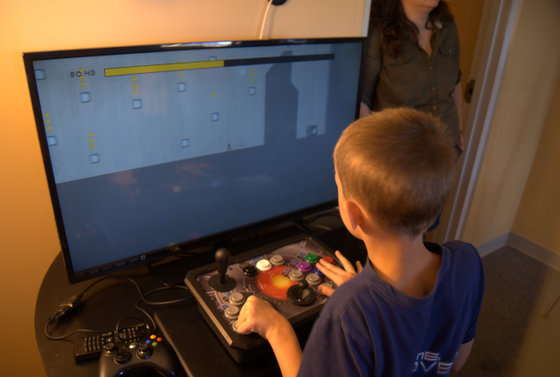

As someone who feels different and separated from able-bodied people, Connor immediately felt complete acceptance the moment he walked through the doors of the Ablegamers headquarters. Normally subdued around strangers, particularly when the center of attention, he opened up quickly. As he played a game of N+ in front of the staff, they were able to quickly see the difficulties he had with games, particularly ones that require precise control. Fifteen minutes spent on the first level were a testament to his typical frustration, and had we been in the comfort of our own home, he would have quit.

They switched games and controllers, replacing the game with Splosion Man, and the controller with Quasimoto’s Axis 2. Five minutes into playing and Connor wasn’t quite convinced. When asked if the much larger controller helped, his response was decidedly “meh”. He continued playing and before long it seemed he was becoming more comfortable with the controller. Levels were getting completed, and as the difficulty ramped up, so did his skill with the controller.

Feeling a bit accomplished, Connor decided to switch back to N+, a game that I’ve decided would make a good punishment in my household (in lieu of timeouts, I’ll make them complete ten levels of N+). Within two minutes of play, Steve and I heard him exclaim “I did it!” triumphantly. Five minutes later he had advanced two more levels; ten minutes later he had vanquished another five boards. By the time it was time to go, the kid who spent fifteen minutes on the first level had advanced to the twelfth, and had received a sharp boost to his confidence. Of course, having a group of understanding gamers surrounding him supportively helped as much if not more than the controller did.

The event had a profound effect on Connor, to be certain. He came home proud of his accomplishments and excited to be able to play video games, even though it will be some time before he gets his custom controller. More importantly, he came home with a desire to volunteer for Ablegamers; he wants to show young gamers with similar disabilities how to use specialized controllers.

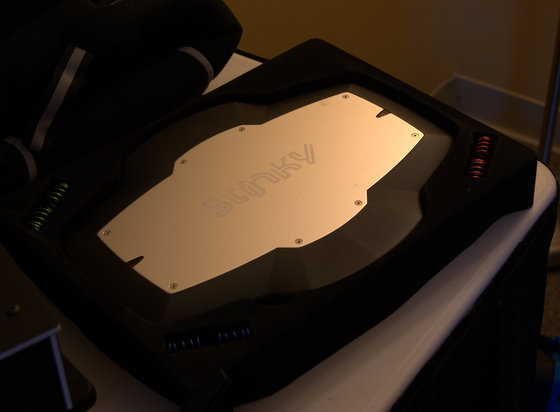

We decided on the Quasimoto Axis 2 controller, which at first glance looks like it would be at home on any arcade machine. Rather than basic on and off switches under large plastic buttons, the Axis 2 is completely analog, with every single button pressure sensitive similar to what you would find on a typical Xbox or Playstation controller. A pair of analog sticks are just out of the bottom, with the L and R series of buttons flanking the stick for easy use in First Person Shooters. It’s a controller that, with continued support in the way of adapters, could very well be the controller he uses for the rest of his life.

Steve also suggested a foot-based controller called a Stinkyboard (which is the best video game related name since 1…2…3…Kick It…Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby), which can be programmed with sixteen different commands and can simulate a mouse as well. While Connor wasn’t initially receptive to the idea of playing with his feet in addition to his hands, as he gets older and plays more complex games, it might be something that would benefit him. Between the Axis 2 and the Stinkyboard, Connor’s new control scheme will cost around $450. It’s certainly not cheap, but with his birthday coming up and after seeing the pride he had in his accomplishments in that short period of time, it’s a small price to pay.

Twenty-four hours after it started, the “Driving Home Accessibilty” campaign had earned $1,265 towards its long term goal of $200,000. It’s clear they have a long road ahead, but these dedicated volunteers seem undaunted, and I expect to see an Ablegamers mobile lab at a gaming convention next year.

A very special thanks to Mark Barlet, Steve Spohn, Craig Kaufman and the rest of the Ablegamers team for having us out and for taking the time to work with my son. You truly are a fantastic group of people doing fantastic work.

Previously By Jason Helton

The 10 Biggest Revelations in America’s Zombie Defense Plan (and Their Real-World Implications)

Ten Amazing American Arcades (That You Can Still Visit)

Daylight Scared the Piss Out of Me: Four Reasons Why It Was Worth It, Five Why It Wasn’t