10 Non-Fantasy Films That You Should Turn Into D&D Adventures in Your Campaign.

|

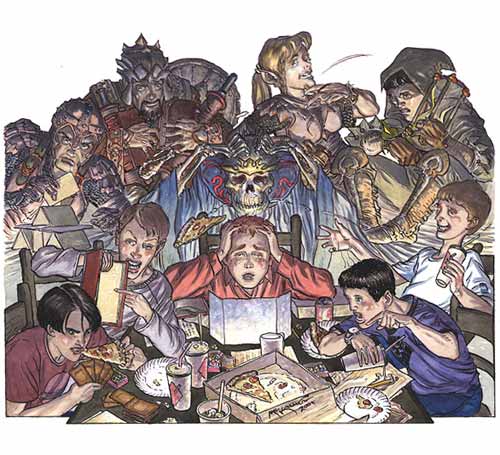

| MW Kaluta |

Every Dungeon Master has experienced that dread moment when the players are about to arrive, but you haven’t had sufficient prep time to put together the adventure they’ll be playing. Sometimes this is due to writer’s block. Most gaming groups have the same person DM the majority of adventures, and coming up with stories week after week can be difficult. This is often where professionally published adventures come in very handy, but most groups have a “completist” player who has purchased and read every adventure. What is a Dungeon Master to do?

In these desperate cases, I often implement James Dunnigan’s Second Rule of Game Design.

“Plagiarize.”

Dunnigan doesn’t mean to actually plagiarize by taking something and copying it verbatim. What he means is that you don’t need to reinvent the wheel when designing a new game. You can build on what has been done before. We Dungeon Masters can do something similar when we design the adventures run for our players. Role playing is a narrative storytelling experience, but not every DM can be Walter Gibson and crank out tens of thousands of words a week. That doesn’t mean that we DMs can’t be creative, however; we have a plethora of sources available to us where we can apply the Second Rule of Game Design.

I’m particularly fond of using television and film. I’m also famous for giving my campaigns series names like “CSI Sharn” or “Invasion of the Brain Moles.” As I mentioned above, when applying the Second Rule of Game Design you shouldn’t copy something verbatim. Instead, use your source as inspiration for something new. The movie or TV show you’re thinking of didn’t have audience interaction, but your game will. Let your imagination, and the imagination of your players, take over.

Today I am offering you 10 non-Fantasy films that you should turn into D&D adventures…that is if you don’t count Science Fiction as Fantasy.

And before you read onward…This Way Be Spoilers.

10) You’re Next

|

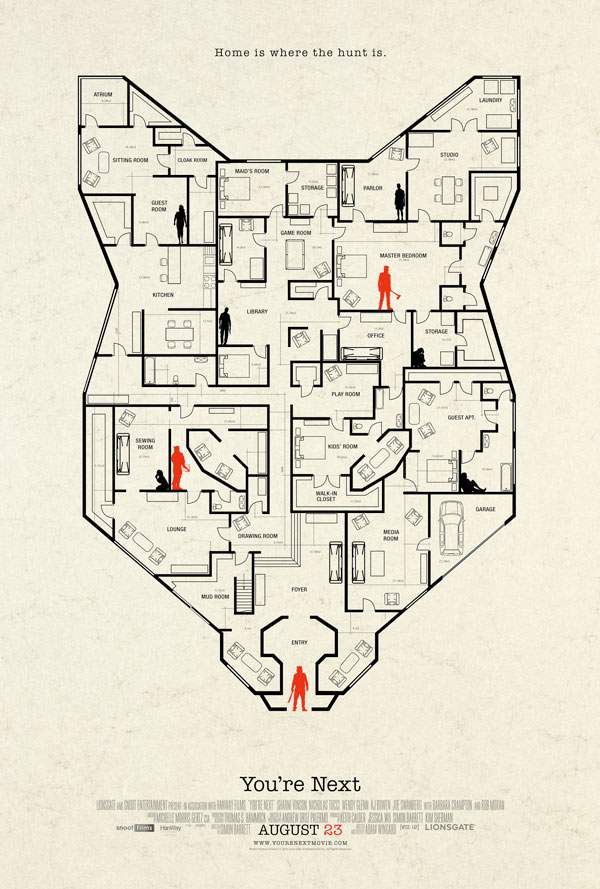

| Lionsgate |

Topless Robot editor Luke Y Thompson wrote a thorough review of You’re Next in which he mentioned that it was the kind of horror film in which the victims have an opportunity to turn the tables on the bad guys. In some ways he understates the case [just tryin’ not to spoil the big twist too badly – LYT] , because the character of Erin (Sharni Vinson) clearly has character levels in a world filled with commoners. She’s not just a character in a film; she’s a player character (PC) with loads of experience who is more than happy to take bad guys to task.

You’re Next is a tale of a wedding anniversary that becomes a bloodbath when three masked home intruders make a violent visit. Family members drop one by one as they desperately attempt to survive the night. That may not sound like a good basis for a D&D adventure, but I think it is perfect in ways that are too often overlooked when we create sessions for our home campaigns. Have your PCs made any NPC (non-player character) friends in their adventures? Are any of them engaged? Do your adventures take place in an urban setting where the players have developed connections in high (or low) places? If the answer to any one of those questions is yes, then you have your starting point.

And before I give a brief synopsis of one way this film can be adapted, did I mention that one of the movie posters provides a bitchin’ map? Because it does, and you should use it.

|

One possible adaptation of You’re Next is the following. The PCs have been invited to a celebration by an up and coming politician in Sharn who has been performing charitable acts deep in the Cogs. It has recently been announced that he has been selected for a position on the City Council and he wanted to share his joy with his friends, the PCs, who have worked with him at some point in the past. As the evening progresses, the PCs notice that there are some conflicts between some of the guests because several rival factions are present. Just as a major argument between a representative from House Cannith and House Ghallanda rises to a crescendo, one of the participants is shot with a crossbow from outside the event. The celebrants are politicians and not combatants and react accordingly. Some members of House Deneith (the bodyguard house) begin securing some of the participants.

Things escalate from here as the players soon discover that some of the bodyguards are in on the slaughterfest and have been hired by one of the evening’s participants. The players manage to get their friend to a secure location…only to find out that he was the one responsible for the slaughter as he owed many of the attendees money and favors he was unwilling to pay. Where does this leave the PCs? What happens next?

9) Escape Plan

Escape Plan may not be the best break out of prison film ever made – I’m pretty sure that’s either Escape from Alcatraz or The Shawshank Redemption. It may not even be the best break out of prison movie starring Sylvester Stallone: my money’s on Lock Up for that one because ’80s. What Escape Plan has going for it is that it is quite simply the “most D&D” of all break out of prison films. The hook for the film is that the Player Characters are experts hired by prisons to help them become more secure. They get hired by the CIA to test how secure a secret prison is only to discover it’s all a lure to take the “escape master” out of action forever. So far that’s not exceptionally D&D, but when you add to it the fact that a pro-democracy hacker head of a secret organization that robs from the rich to give to the poor is in the prison too you’ve got some room for a great D&D adventure. It is especially good for a first adventure that can be used to launch a campaign.

Have the players make characters as normal, but make sure that at least one of the characters has some link to the main campaign city’s slums. The player characters are all employees of one of the Dragonmarked Houses of Eberron – or have some equivalent patron depending on the campaign – and have been hired by House Deneith to investigate if any prisoners in the Dreadhold have found a means to escape. The players are merely supposed to go to the prison, hang out long enough to get to know some of the players, and find out if certain NPCs have found a way out. When they get the answer, they are supposed to give one of the guards a special code and that’s it. Or is it?

It turns out that the PCs’ current patron has partnered with a rogue faction of House Deneith and is running illegal gladiatorial games in the Cogs – because prison movie – and fears that the PCs’ connection to those slums might lead them to discovering the connection. The patron needs the PCs out of action quick and is using his Deneith allies to get the PCs out of action. The Dreadhold is impossible to break out of and no one has a means of escape. Or do they?

Turns out that a key political figure had been sequestered to the Dreadhold and has some means of getting out of the impregnable prison. The only problem is that this political figure cannot trust anyone currently imprisoned. It is a prison filled with the worst of the worst, after all. Using contacts outside of the prison, this figure discovered that the PCs had a connection to the Cogs and were new hires working for one of the villains responsible for the political figure’s imprisonment. The politician is the person responsible for leaking the PCs connection to the slums and thus responsible for their imprisonment. Do they help the politician? Do they attempt to escape on their own? Either way, they’ve got an antagonist or two on their hands and you have a great D&D adventure. If you are a Mystara fan – and I am – you can use the Veiled Society as your villains as well.

8) Assault on Precinct 13 (Rio Bravo)

The situation in these films is similar in some respects to that of You’re Next in that they involve an encounter with individuals attempting to invade a building and murder the inhabitants. There are some key differences, though, that provide rich fodder for adaptation. Each of these stories features a small, rag-tag group of protagonists who must defend a person or location against a much larger force. In Assault it is a small group of police officers holding off a large gang on a killing spree. In Rio Bravo, the protagonists are holding off a gang who seeks to break out a prisoner. One could easily add Straw Dogs, The Alamo, or 300 to this mix of films for inspiration. The most difficult choice to make in adapting this into an adventure is picking between the motivation of keeping a prisoner secure for transportation/protecting someone as opposed to just staying alive. While I might typically choose the keeping the prisoner secure motivation, not in small part because I am a huge Leigh Brackett fan, in this case I’ll choose the just surviving motivation.

The adventure begins with the player characters entering the town of Waybridge. The characters quickly discover that people are fleeing the town because a horde of orcs has been cutting a murderous swath across the countryside and the townsfolk want to get to a safer location. What the PCs know, that the townsfolk do not, is that Holdfast Keep recently had a wall collapse during an earthquake and will be unable to protect the growing influx of desperate commoners.

Holdfast is two days travel from Waybridge and is home to 2,000 citizens. The players have to choose between attempting to stop the horde at Waybridge, or at least delaying it, and reporting the horde to Holdfast. Given the size of Holdfast’s population, even if the players deliver the news in town for Holdfast to evacuate it won’t matter. Marching the 2,000 citizens, plus a thousand or so more from surrounding villages, the ten days to the next large city would likely result in a great deal of death. So the players are stuck in Waybridge and must find a way to stop the horde. Thankfully orcs tend to disperse if their leader is killed. Can the player characters turn Waybridge into a murder gauntlet that would make the 13 Assassins nod in awe?

7) Quantum of Solace

The second Daniel Craig entry in the long lasting 007 series has received no small amount of criticism, and I think a lot of the criticism is misguided because it doesn’t understand what the actual narrative of the film is. This isn’t a movie about a secret agent who has seen the woman he loves drown and who seeks revenge on the killers. That’s what the agency he works for thinks its about. This film is about a secret agent who sees how vulnerable the head of the agency he works for – a parental figure – is and decides to perform exploratory surgery throughout the global espionage community to find who infiltrated that agency and how. This is a film of investigating clues on a timeline of “needs to be known yesterday before M was attacked.” It is this narrative that makes for the perfect D&D adventure.

The PCs are celebrating a successful adventure and receiving acknowledgement from a noble or patron they have a close relationship with, either that or with a family member. During the celebration, their patron is attacked by his or her own bodyguards, characters the players know and trust. Maybe even characters the players have adventured with in the past. The players stop the attack with minimal damage, but as the attacker dies it is made clear that there are more murderers waiting in the shadows. The killers could be anyone and the patron won’t be safe until the source of money and training is eliminated.

The PCs have only one small piece of information, a name, and must unravel the rest from there. In designing the adventure, pick four or five key locations you’d like to use, but don’t hesitate to riff off of the players’ ideas. Since anyone can be the enemy, let the players help you determine who it is. You can use Kenneth Hite’s ingenious Conspyramid as your framework filling it out as the narrative unfolds.

6) The Seven Samurai (The Magnificent Seven)

If you haven’t adapted The Seven Samurai into an adventure, you need to do so right now. Kurosawa’s classic was pretty much designed to be a campaign starting adventure. It does share some elements with the Assault on Precinct 13 story, but there are some significant differences that make it a great first adventure. This is especially true if you add elements from The Magnificent Seven. The basic premise of the story is that a group of bandits has been attacking a small village and will be doing so again at the next harvest when the village has merch worth looting.

In other words, a group of WoW players have found a good spot to farm that respawns every couple of months. The villagers are sick of being murdered over their paltry supplies and have decided to hire skilled swordsmen to aid them in their time of need. The swordsmen are recruited one by one in a way that can easily be mimicked in your local game.

It’s not the film’s narrative that I’d use when borrowing from The Seven Samurai, though you can feel free to do so. It’s the means of introducing the characters. The Seven Samurai spends a large portion of the film putting the team together. We get to see the characters in their lives before the adventure and get a sense of who those characters are through the use of well-directed subplots. This is what you should do when creating a campaign starting adventure based on The Seven Samurai. Instead of having all of the player characters happen to all be hanging out at the local village inn, or having them see want ads posted on trees, or summoned by the baron, you can begin the evening with one character’s back story and move from that character to the next building up background narrative as you move along. Sure, you can use the village being attacked by bandits to bring in your own Kambei, but let each player’s character have their moment of pure roleplaying introduction. It beats the hell out of looking at each player and saying, “okay…now introduce yourself.”

5) Alien

As a source of inspiration for a D&D adventure, Alien is a perfect choice. It is a classic tale of man exploring the unknown and engaging in a monster hunt, with a touch of mistrust added in for good measure. One of the stories that inspired the film Alien, A.E. van Vogt’s Black Destroyer (the Black Gate magazine website has a nice overview of a collection that contains the story), has been an almost endless source of inspiration throughout science fiction and fantasy. The displacer beast, a classic D&D monster, is based on the coeurl described in Black Destroyer. The classic Star Trek episode The Man Trap takes the coeurl and transforms it into a lonely shape-changing creature. Surprisingly, it’s not the monster hunt aspect that made me select Alien as a perfect film for adaptation. After all, most D&D adventures are monster hunts of a sort. Instead, it’s the vulnerability of the crew of the Nostromo that makes it ideal.

I’ve run too many D&D adventures where the player characters are over-prepared for almost any obstacle. Between all the bags of holding, portable holes, pints of oil, 10′ poles, and vials of holy water, the player characters might as well be a wandering general store. It sometimes seems that there is no threat I can throw at the players that they haven’t already prepared for in some way. The question a Dungeon Master who is adapting Alien has to ask is “how do I separate my players’ characters from their stuff in a way they know is temporary, but which allows me to run a session that uses character vulnerability to create a sense of horror?” It’s a good question, but unlike in Alien this isn’t going to happen while on a foray into the unknown. That’s when PCs are most prepared. PCs are least prepared when they feel safe and when they can be lulled into temporarily forfeiting their equipment. So here’s how I’d adapt Alien:

The player characters are entering a relatively large village or city where the local constabulary requires that the characters leave their weapons and weapon-like equipment with the constabulary. All the weapons are stored at the town’s armory and this town has a reputation for being safe and lawful. It’s just standard operating procedure in the town, just like it was for Wyatt Earp when people entered Tombstone. It’s not that you’re not allowed to have weapons, just not in the protected areas of the city.

Here’s where one of the key components of the film Alien comes into play. In the film, the android Ash works against the interests of the crew and to the benefit of the monster. In the Star Trek episode, the monster can shape change. In the original story, the traditional means of restraining the monster are useless and interdepartmental rivalries prevent sufficient cooperation to handle the problem early. What we need is a traitor and a monster. Since I am a fan of The Man Trap and the original short story, let’s make the monster a vampire and let’s make it so that the constabulary is particularly resistant to the PCs getting their weapons back. This can be either because the constabulary doesn’t believe the PCs, or because they think they can handle the situation. How do the player characters battle a vampire without the use of their Sunswords and scads of vampire-hunting wares? What if the majority of their magical components were also confiscated? This is a great time for players to learn what the actual material components of their spells are, and the locating and acquiring of non-purchased versions of those components can be a nice subplot of its own.

4) Taken

Like Liam Neeson’s character in Taken, the player characters of any role-playing group are in possession of a very particular set of skills. In Taken, the protagonist’s daughter is kidnapped by human traffickers and he uses his particular set of skills to run roughshod over their organization and kill half of the Parisian underworld. It is unlikely that any of your player characters have children, but it is likely that they have patrons or allies who do. This provides a perfect opportunity to run an adventure based on Taken, but it is also one that might seem a bit staid. The damsel in distress tale has been done over and over again. Sometimes the stakes are plausible and the story works, and other times it’s more than a little exploitative. So we might not want that to be the inciting incident. How would I do it?

The key narrative point here is the stakes set by the abduction. In Taken, as in Man on Fire, the abducted person is one of the few things keeping the protagonist from either suicide or psychopathy. That’s not a good stake for an adventure, but the abduction of a person key to a negotiation is a good stake. This was the stake used in Escape from New York and it’s one that fits nicely into a D&D urban/political adventure. Perhaps an ally of the player characters has a key piece of information that will prevent war, or maybe the PCs’ ally is the only person who can perform a certain task. Whatever the case may be, the person’s abduction means that people will die. You can set the level of death at an appropriate scale for your campaign. Perhaps the abductee is the only person who knows how to shut off one of the billows in the Cogs that’s about to blow and thus is needed to stop a massive loss of life.

Alternatively, the scales could be much smaller and the stake be only the loss of one life. The stake must be life or death, though, for the PCs, while the stakes for the abductors must be very low. In Taken, it is low-level criminals out to make a quick buck who take the daughter and pass her up the conspyramid (and there must be a conspyramid). In an adventure adapting Taken, the PCs should not stop until they have ensured the victim is safe. They can stop at that point, but that just leaves room for more adventure.

3) The Art of the Steal

The Art of the Steal is not a great movie. It’s a heist movie that lifts a lot of imagery from Guy Ritchie’s film Snatch, but what sets it apart is its use of a prior failed heist to establish the background for the current adventure, and that’s what makes it a perfect film to adapt to D&D. Many movies or stories are either the first time something has happened, or they reveal the background piecemeal throughout the film’s narrative arc. The Art of the Steal gives us all the background we need in the first ten minutes. Interestingly enough, when I first watched the film I treated this background as mere fluff and it wasn’t until halfway through the film that I realized it had established the motivation for almost all of the action of the film. While The Art of the Steal isn’t a sequel, it provides a good structure for a DM to use as a means of creating adventures that are sequels to past gaming sessions.

Does your D&D campaign have recurring NPCs? I don’t mean recurring big bad villains. I mean NPCs who are a regular part of the PCs lives, and who are sometimes a bigger pain in the ass than they are a benefit? That’s what we need here. In my adaptation of The Art of the Steal, I’d have the adventure be a followup to the Escape Plan adventure I discussed earlier. What if the PCs escape, but they don’t let their betrayer know that they know they were betrayed? What if they treat their escape from the Dreadhold as if it went exactly as it was supposed to with only a minor blip regarding the lower level guards not having known about the password? What if the player characters decided to convince their former patron that they were still “on board” and that they wanted a piece of the action of the underground fighting league that House Deneith was running? Greed can go a long way to convince someone you’re being truthful. Obviously, this isn’t an adventure that is custom made for a Paladin, but it is good for almost any other group. Have the PCs team up with legitimate law enforcement to bring down the fighting league, while simultaneously ensuring that their former patron is imprisoned and impoverished.

2) The Siege

Edward Zwick’s film The Siege is a pre-9/11 look at how the United States would react to terrorism. It is off-target in a few respects, but in others it is remarkably close to predictive. In the film, terrorist attacks in New York City lead to the detention of American citizens and the use of the military on American soil. The protagonist of the film is trying to find out who is responsible for the attacks, while also trying to advocate for the rule of law. It’s an interesting conflict that the film kind of awkwardly stumbles around, which leaves a lot of room for adaptation into a D&D adventure.

Were I to adapt this adventure, I’d likely place it in the World of Greyhawk and have the Scarlet Brotherhood implement a series of murders while making it appear to be the work of dissatisfied Rhennee. The Lord Mayor might react reasonably at first, but if the attacks target a specific nation’s embassy, this might lead that nation to request additional authority in the Free City. Let’s say that the Lord Mayor allows Keoland some additional latitude to protect its delegation and hires the player characters to investigate the attacks. The player characters would have to simultaneously negotiate with the Ambassador of Keoland who seeks to bring in a cohort of knights, the Lord Mayor who is happy to give Keoland some rights of self defense but not as much as they are taking, and the Scarlet Brotherhood. Can the player characters discover that the Brotherhood is behind the attacks in time to prevent a new outbreak of war across the Flanaess?

1) The Most Dangerous Game

The Most Dangerous Game is one of my favorite adventure stories. The basic premise is that an insane big game hunter arranges for people to become shipwrecked on his private island so that he can hunt them. One thing I have to say about us Dungeon Masters is we just don’t have villains actively hunt down player characters for sport near as often as we should. As I mentioned in the discussion of Alien, player characters rarely adventure unprepared. They’ve got magic items, spells, and all the equipment they need in order to go off on a quest. It seems like every time they meet an NPC, it’s because the NPC wants to hire them, beg them to save some one, or send them on some kind of adventure. What if you use that assumption against your players? Have them think they are being hired by a wealthy NPC to recover a lost magic item like Blackrazor, only to discover when they wake up from their slumber that they are in the middle of a hunting ground and without their beloved swag?

If you want great example of how to adapt this story well, and keep the team vibe, watch Disney Pixar’s The Incredibles. In that story Mr. Incredible is hired to help a “brilliant yet reclusive” scientist recover his robot gone wild, but that’s not what is really going on. What’s really going on is that Mr. Incredible is being hunted by Syndrome who wants to see him dead. This is what you should do with your player characters. Have them enter into a situation with either someone they trust from past experience, or who they hear about from another source. Have the NPC offer to hire the heroes to recover Blackrazor, which will make the players think they are playing in an updated version of White Plume Mountain as good cover for your nefarious plan, and then run from there.

The key here is to have the players try to survive without their gear and using their wits. There should be opportunities for them to acquire equipment, but they should start without any. Let this be a test of the player’s creativity. Give them opportunities like the one Kirk has in the original series episode Arena to get what they need to win, but let them role play the desperation of not having their usual arsenal.

Those are only a few movies that can be adapted into D&D adventures. Any film is great source material. I’ve never designed an adventure based upon a Jane Austen novel, but I think one could work pretty easily.

What films do you think are ripe for ripping off?

Previously by Christian Lindke:

10 Geek Holidays and How to Celebrate Them

7 Reasons I, Frankenstein Is Like the Greatest RPG Campaign Ever GM’d

The 10 Best Superhero Role-Playing Games

From The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle to Dallas: 10 Strange Licensed RPGs

Ten Ways to Make a Dungeons & Dragons Movie Not Suck

Related Posts

-

The Transformers Hall of Fame Inducts Michael Bay, Immediately Explodes

Warning: This may be more horrible than today's FFF. Michael Bay

by Rob Bricken -

Geek Apparel of the Week: My Other Ride Is a Light Cycle

?This majestic hoodie -- also available in t-shirt form -- has

by Rob Bricken

About The Author

Christian Lindke

In between studying for a Ph.D. in Political Science at the University of California, Riverside and being a non-profit Program Director, Christian Lindke spends his time experiencing as much of pop culture as possible and playing role playing games. He hosts the Advanced Dungeons and Parenting Blog and holds an M.B.A. in Marketing.