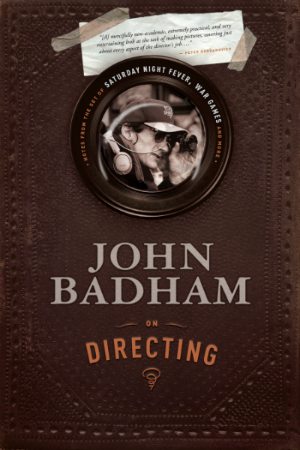

TR Interview: WarGames and Short Circuit Director John Badham Talks Tech

|

| B/W photo by Joe Lederer |

He has directed many, many movies you’ve heard of, from Saturday Night Fever to Stakeout to the Frank Langella Dracula. What you may not have known is that he literally wrote the book on directing, or rather, On Directing. Now available at Amazon and wherever else they sell books these days, it’s a collection of Badham’s best tips for those who would aspire to follow in his footsteps, or merely wish to read about specific examples of when he had to put his own pointers into action with the likes of Goldie Hawn and Mel Gibson.

In addition to his book, though, I couldn’t resist getting in a few questions about his big two sci-fi classics of the ’80s – including what he REALLY thinks about Wall-E’s resemblance to Johnny 5!

Luke Y. Thompson: When I first got this press release on the book from you, I was sort of expecting an autobiography, and it’s more of a “how-to” to direct. How did you come up with that as the goal for the book?

|

John Badham: I really didn’t have any interest in writing an autobiography, because it all sounded really boring to me. I thought, “Who cares about reading this?” On the other hand, I know from my teaching and so on over many years that people like specific, very specific kinds of stories, and they learn best from those very kind of specific things, and so my first book was really designed to deal with how to work with actors. Having found that students desperately wanted to know what you do when an actor won’t do what you tell him to do, and that’s something that perks them right up.

I think because of my background in theater and coming from Yale drama school, theater directors put a lot more focus on working with actors than do film or television directors, who have a tendency, and I say tendency, not as an over-all [statement], to be focused on the visual, the equipment, the hardware, the photographic aspects of it, and not so much on the human being part of it. So both of these books really delve more into the human being part of it, and how best for directors to try to start to confront this and handle it.

LYT: Do you have in mind as the audience for these books primarily the academic, sort of classroom setting, or do you think there’s a much wider interest just from the casual reader, who may never want to direct a film, for example?

JB: Well, I think there’s a wide – the people that I know that read it that are not film makers but are just reading it for a lark, they find it very entertaining because the stories in there are related to people that they know and that they have ideas about, a different perspective. Some verge on the gossipy, and people always love a little bit of gossip. I think, in my first book, I would have two reactions if somebody that I interviewed in the book passed away. I’d go, “Oh my god, that’s terrible! I’m going to miss them.” Then I’d go, “Oh, thank god! They can’t sue me!”

|

| Nick of Time |

LYT: Is there a process by which you have to vet every story and run it by their reps, or do you just kind of say there were enough witnesses on the set that I can just go ahead and say this?

JB: No. I mean, if it had happened to me directly, which is mostly the case, then I would go for it, though in a couple of cases I would call the person and say “I’m writing the book, and I’m going to say this. How does this sound to you?” I’ve got some stories in the first book about Frank Langella, and I called Frank and we exchanged copies of the draft back and forth, and I adjusted it to make him content that it was okay and fair, and I had gotten a couple of little facts wrong, and perspective wrong, so I was happy to do that. One Clint Eastwood story, I know I went and tracked down the production manager who was on the set when one particular event started, and made sure that it was not just an urban legend.

LYT: Do you think that there are larger lessons to be learned, in terms of how to deal with people, to be derived from how a director works with actors and so forth?

JB: Oh, yeah! I think a lot of my theories and principles on it are derived from reading that I’ve done on child psychology and dealing with your children and how to raise your children. Not that I put actors in the same category as children, but a lot of the same principles about taking people seriously about their concerns works with human being. Books like The One-Minute Manager – I’m a big proponent of that, because it really does deal with how to get the best from your people.

LYT: I wanted to ask you a question about technology in general, since you’ve made two sort of iconic movies: Short Circuit and WarGames, that both ultimately come to the conclusion that technology that we create to destroy will ultimately become benevolent. Was that a coincidental theme that you just happened to like the stories and that was the theme there, or was that something you really think about a lot?

JB: Yeah, I would actually add into that and make a little trilogy, adding in Blue Thunder, because Blue Thunder deals with a lot of stuff that we’re looking at right now very hard – government’s intrusion into our lives and how much intrusion is okay. Blue Thunder was released before the year 1984; that was an iconic year because of George Orwell’s novel all about government intrusion, looking into the future. All three of these films deal with the dangers of technology and how it can go off-track, sometimes in a very funny way, as in Short Circuit, or in scary ways, as in the other films. We’ve always been worried about how computers can go wrong, but what we’re seeing mostly is either computers going wrong mechanically, or because of elaborate hacking designed for pretty malevolent criminal purposes.

LYT: When I was a kid, I was a huge fan of the Blue Thunder TV series, which I think lasted an entire season.

JB: Right, right; just one season.

LYT: I don’t think any of those themes really made it into the show, did they? How did you feel about the show, in general?

JB: I was not a fan of the show. I had a lot of troubles with it. I think they just were looking to make an entertainment, and it was kind of, not a clone, but a copy of The A-Team. It became that pretty quickly. As I told them when they talked to me first about it, I said “I know you’re not going to be able to fly that helicopter very much – it’s bloody expensive! And on a TV show budget, I don’t think that’s really in the cards.” Sure enough, after 3 or 4 or 5 episodes, they put people down on the ground in a big van, running around that way, doing something more affordable, and forgetting about any themes of invasion of privacy, or anything like that. It just became another cop show.

LYT: Back to the technology theme – in terms of film making, how does that affect the process for you these days? In terms of everybody democratizing the process a bit, but also the big movies kind of get lost in technology and seem to treat the actors more and more like objects.

JB: Oh, yeah! Oh, they just love the idea of, “Look here! We can just do motion capture – we don’t really need to have the actors around very much.” We can do all of this and the actors are just like puppets being moved around. So it’s interesting to me that a film that deals with human beings very nicely, like Blue Jasmine, recently, is attracting a pretty good-sized audience of people that are interested in the human being side of it.

I just came back from Toronto yesterday, and it took me two days to get into that movie, because in the big theaters that they were running it in, they were sold out in every single show. I went in at 7 o’clock at night and came out at 10 o’clock at night, and there were 600 elderly people – it seemed to be mostly an older audience – lined up to see that 10 o’clock show. I think there is always a good audience out there for it, and if they don’t find it in the theater, they find whatever’s the best on cable – things that they can relate to, in a way other than teenage boys kind of movies that we get in the summer.

LYT: So ultimately, are you pretty hopeful that technology will, like Joshua in WarGames, learn to improve, rather than be a danger? Or like Johnny 5, develop a benevolent kind of personality? You obviously think a lot about the cautions and the dangers, but there’s sort of this ultimate message that it’s for good in the end. Do you feel that way?

|

JB: Well, I think it wanted to be for the good, and we’ve found a lot of good out of it, and we find as computer technology gets smarter and smarter, it can be extremely helpful to us, and we’re using it. All those devices we’re carrying around; iPads, iPhones, SIRI – all of these things that are really, really quite helpful to us, on so many levels. It’s still in kind of a swing stage, where it’s going in both directions at the same time. We see it messing up our power grids, we see computer mistakes causing giant problems, not actively, malevolently coming after us, but the malevolence seems to come more from human beings who are using it more to suit their own purposes.

LYT: A lot of people, when Wall-E came out, said he seemed to be based on Johnny 5 in design. Do you see that? Do you see similarities there?

JB: Oh, God yes! Yes I did! (laughs) I think David Foster, my producer on that film, was redder than red had ever been in the face. He was just purple, he was so mad! The similarities – we were all very closely involved in the design of Number 5, so we saw all the similarities. I had the attitude that the flattery is the greatest kind of compliment, and it’s very nice. I’m sure that we didn’t get all of our elements quite from scratch, so that’s good that way, and I’m glad it worked. But David was not so benevolent as I!

—

On Directing , by John Badham, is available now.