10 Secrets From the Cast & Crew of the ’80s Rambo Cartoon

|

“His name was Rambo, and he was just some nothing kid for all anybody knew…“

So begins David Morrell’s harrowing novel First Blood, which I read in one white-knuckle sitting more than three decades ago. Back then, a film adaptation was still a ways off, but the cinematic quality of the writing made a movie version inevitable. The idea that such a brutal book could inspire a children’s cartoon, however, was completely absurd. Which makes the 1986 animated series Rambo: The Force of Freedom one of the most unlikely kids shows ever broadcast. Since this month marks the 30th anniversary of the blockbuster movie Rambo: First Blood Part II, I spoke with the cartoon’s cast and crew, including Rambo voice actor Neil Ross, head writer/story editor Mike Chain and writer/assistant story editor Jack Bornoff, about the challenges and rewards of bringing Morrell’s iconic character to the small screen.

Neil Ross is an acclaimed voice artist whose work can be heard in classic TV shows like G.I. Joe, Transformers and Voltron. He talked with me about portraying Rambo, and reminisced about working with his fellow cast members on the animated series.

1. “That doesn’t sound anything like Stallone.”

|

| Neil Ross |

Topless Robot: I’m curious what your first exposure to the character of Rambo was. Had you read the novel or seen any of the films before working on the series?

Neil Ross: I never read the novel, but I saw the initial film. I’m not sure if I saw the others, to be honest with you. I may have caught bits and pieces of them on TV, but the only one I saw from start to finish was the original.

TP: You’d already been working in animation for quite a while before the Rambo series came along. How did you get the job?

NR: It was an audition. I don’t know how many other people read for it. It was sort of a funny thing, though. I went in and they said “Now, we don’t want a Sylvester Stallone sound-alike.” So I said, “Got it, no Stallone.” Then I started reading the copy in a Sylvester Stallone voice, just to make them laugh. And they jumped on the button and said “That’s it! We love that!” So I said “But I thought you didn’t want a Sylvester Stallone voice?” And they said “That doesn’t sound anything like Stallone.” So I quickly backpedaled and said “You’re right! It doesn’t!” Then a week went by and my agent said they cast someone else in the part. So I thought, well there you go. There’s no accounting for taste! :laughs: But then they called me back and said the actor they hired, for whatever reason, didn’t want to do the show, so you’re the guy!

TR: When you’re working on a voice to use in an audition, do you go in with a few different versions, or stick with the one that you think sounds best?

NR: Well, usually what I do is go in with my best shot, or what I think is my best shot. But you always try to have three or four different approaches in your hip pocket, in case they say “What else have you got?” So in a lot of cases, I may come in with as many as five different approaches, which are now all lost in the mists of time. :laughs: I seem to have had a lot of success with what I call ‘failed impressions.’ I mean, the voice I did for Rambo was probably an attempt I made to do a Stallone impression at a party just to crack a few people up.

TR: I hear echoes of Stallone’s voice at times in your portrayal. There’s a Brooklyn twang that sounds a bit like his role in The Lords of Flatbush.

NR: It’s an impression that would get me thrown out of a comedy club! But I guess there were enough echoes of him to where they liked it. Plus, they probably thought there’s no way he’ll ever sue the studio because it’s just so bad! :laughs:

2. Barefoot in the Studio

|

TR: When recording Rambo, did you work in an ensemble with the other actors present, or were the voices recorded separately?

NR: We worked ensemble. Back then, they wanted the entire cast together. The rule was, everyone must be there, no exceptions. That all changed somewhere in the ’90s when they started using celebrities, because those people just aren’t available that much. So they got into a mindset where you had to record everyone separately. In fact, I recall one time when I arrived for a show and the other actor was there, and they started to pull us in separately. I said “Why don’t we just go in together?” Well, they looked at me like I said “Why don’t we jump on a duck and fly to the moon!”

TR: I imagine it must be helpful to have your fellow actors present to play the scene.

NR: Well, that’s the thing from an acting standpoint, of course! I love to hear the feed line. If we’re both working separately in a vacuum, I don’t know how they’re playing the scene. It’s like a tennis match. Two good actors working together make each other better. It’s like a great volley, where after a while you don’t care who wins the point, it’s just so breathtaking.

TR: You worked with actor James Avery on Rambo. He played the character named Turbo. Most people probably remember him as Uncle Phil on the sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

NR: I enjoyed working with James a great deal. He was a wonderful actor, with a tremendous background in Shakespeare. I remember he used to do this funny thing when we worked together. Because he was black, white people would occasionally try to talk jive with him! :laughs: It was ridiculous. They’d come up to him and say “Hey baby, wass’ happnin!” So James would rise up to his full height and look down at them and growl “Excuse me! I don’t know that kind of talk! I’m from New Jersey.” :laughs: It was the perfect comeback. Another thing I remember was that he always worked barefoot.

TR: You’re kidding.

NR: No! He’d come to the studio and immediately take his shoes off. And I thought, if it helps, more power to him! He didn’t need the height, that’s for sure. He was already tall. Even with his shoes off, he towered over everybody.

TR: One of my favorite actors in the Rambo cast was Michael Ansara. He was a Syrian-born film and television actor who was often cast as a Native American. What was it like working with him?

NR: He played General Warhawk on our show. And yes, he was often cast in Westerns. In fact, the first time I saw him, and this is going way back, was on a show called Broken Arrow, where he played Cochise.

TR: The only characters on the show that also appear in the book and the movies were Rambo and Colonel Trautman. He was voiced on the series by Alan Oppenheimer in a performance sounds fairly similar to Richard Crenna’s from the film. Was that on purpose?

NR: Yeah, they kind of had the same crisp delivery, but I don’t know if he was making a conscious effort to imitate what Richard Crenna did. You’d have to ask Alan about that. I’ve worked with Alan on many different shows. He’s wonderful. You go to these autograph conventions and, of course, the thing that most of the fans remember about Alan is when he played Skeletor on He-Man! His table is always surrounded by tons of people when he does an autograph session.

3. Thumbs Down for Siskel and Ebert

|

| LA Weekly |

TR: Rambo was fairly controversial, because it was the first cartoon adaptation of an R-rated film. Were you aware of that when the series was airing?

NR: I seem to recall that there was a certain rumble in the press about it. But if you look at the actual shows, they were almost laughably non-violent. Rambo bends over backwards to avoid violence. The only thing I remember is tuning in one night to watch Siskel and Ebert, and they suddenly went into this rant about how there was going to be a cartoon Rambo and they were just outraged about it! They said “Hasn’t Sylvester Stallone made enough money off of this character yet?” And I thought, don’t these two nitwits know that he doesn’t own Rambo? He’s just an actor for hire! He had, to my knowledge, zero involvement in the animated series. Don’t these guys do their homework? I never watched their show with the same feeling after that.

TR: For a show like Rambo, do you typically get the scripts in advance to prepare, or do you just show up at the studio and read it cold?

NR: In those days, I don’t recall ever getting scripts in advance. That started happening much later. There was a big sea-change in the ’90s and suddenly you’d get booked for a show and the doorbell would ring and there’d be a messenger there delivering a script to your house! But back then they’d pass them out as you walked into the studio. Usually you’d get a rehearsal, and that would give you time to figure it all out.

TR: Rambo spawned a popular line of toys. Was that your first experience having an action figure made of a character you were playing?

NR: Well, around that time I was doing Voltron and G.I. Joe, so it wasn’t a unique experience. And we never had any contact with the merchandise at all. I mean, if I wanted to see my action figure I’d have to go down to K-Mart and buy one! They didn’t bring them to the recording sessions, or even show us pictures. The only time you’d hear them mentioned was if the show got cancelled. They’d say “The toys aren’t selling.” I could never figure out if they were joking about that or if they were serious.

4. An Astonishing Actress

|

| eBay |

TR: You worked on 65 episodes of Rambo. Do any of them stand out as particularly memorable, or is it all just a blur at this point?

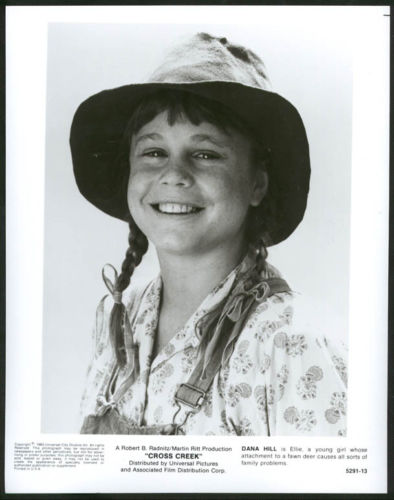

NR: It’s a blur, with one important exception. I worked with a young actress named Dana Hill. She passed away quite a while ago. She was someone whose work I’d admired in the past, and she came in to do a guest spot on the show. She and I had a long scene together, and the way the microphones were set up, I couldn’t see her, because she was standing behind me. But I really started listening to her, and I just remember that scene going so beautifully, largely because of Dana. I just listened to her line readings and responded to them. And it just worked like a charm. I remember that scene very well. She was such a talented woman, and it’s so sad that she passed away so young. The two movies that I first noticed her in were Cross Creek and a lovely picture with Albert Finney called Shoot the Moon. And I just remember being struck in both movies by how good she was! I thought, “How do you get to be that natural in front of a camera at that young age?” She really was astonishing. It was a treat to work with her, and I remember the scene going so beautifully. That’s my strongest memory from Rambo.

—

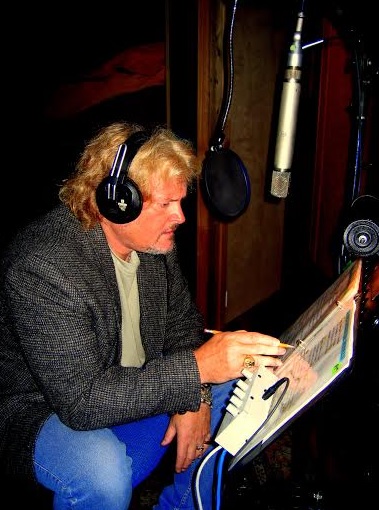

Mike Chain is an actor, writer and musician who has worked on shows like Transformers, She-Ra: Princess of Power and Police Academy: The Series. He spoke with me about developing Rambo: The Force of Freedom for Ruby-Spears and Carolco Television.

5. A Background in Combat

|

| Mike Chain |

Topless Robot: How did you get the job as Head Writer and Story Editor on Rambo?

Mike Chain: Well, I was working at Ruby-Spears, and I was their all-purpose guy. I wrote fantasy, science-fiction and comedy, and since my background was in weapons and martial arts, it made me a shoe-in for Rambo. To begin with, they asked me to write a trailer for the show. We were working with Carolco at the time. They were the film company that produced the Rambo movies.

TR: You mentioned weapons and martial arts. Could you describe that background?

MC: I used to shoot in competition. Combat style. I’m a small-arms expert, and I taught martial arts for years.

TR: That makes a lot of sense, since the Rambo series is surprisingly authentic when it comes to weaponry.

MC: Yes, the weapons were always accurate. I always used the actual weapons, unless we were introducing a specific toy that the toy company was selling. But all of the aircraft, vehicles, tactics and weapons were totally accurate. It’s part of my military background.

6. Rambo Versus Peggy Charren

|

TR: Rambo was somewhat of a risk for Ruby-Spears, correct?

MC: They were basically in trouble when they came to me with this. I was the story editor on another show that we were going to pilot on. And they said “Let’s just make a trailer for Rambo and see if we can sell it.” So they asked me to write a two-minute trailer for the cartoon show, and I did, and we filmed the thing and then just kind of put it aside. And much to my surprise, about three months later they said “We’re starting on the show right now.”

TR: That sounds awfully quick.

MC: It had never been done before. Usually you’d have like a year or so to work up to that. We had three months! So I had one week to put together a five-part miniseries, which was basically the pilot for the show. It ran five days a week.

TR: And what was the reception like?

MC: The episodes pulled the highest ratings that had ever been pulled for a cartoon like that. They were pulling prime time numbers for an animated show. Unfortunately, it ended up killing us because it attracted the attention of Peggy Charren and Action for Children’s Television. That got us involved in all the politics. ABC was scared of getting death threats and people talking about violence in children’s television and all that stuff. And it was just horse-pucky! Because in all 65 episodes of Rambo, no one ever gets hurt, let alone killed, with the exception of Rambo himself who breaks an arm falling out of an airplane in one episode.

TR: I see what you mean. When I revisited the series recently, I found that it really does emphasize action over violence.

MC: That was intentional. My very first gig in television was writing a children’s show that won a Peabody Award. So I was versed in working with kids, and I didn’t want Rambo to have an adverse effect on the psyche of children. I wanted to create positive role models and teach morals on the show. Every episode had a moral to it.

TR: I read online that there were child psychology advisors working on the show to give some guidance. Was that true?

MC: That’s more horse-pucky. They were in so much trouble on the show, because instead of having a year to get ready, they had to do it in a few weeks. We just wrote the show, and the scripts were approved immediately. There were no rewrites on my stuff. I hired all the writers. Everything was rewritten to fit the format, and we put it on the air. There were no child psychologists involved. We had no edicts from above. I mean, obviously we weren’t going to be doing a cartoon where we were killing a bunch of people. But the show could have been a lot more violent, like G.I. Joe.

TR: So what caused all the controversy?

MC: The title of the show, and the ratings. That caused Peggy Charren and all the nutcases and anti-violence people to go after Rambo. They practically ignored G.I. Joe, which was actually violent, and we weren’t! And that scared ABC. So in spite of the ratings, which were through the roof, they pulled the show and started airing it at 4 in the morning, to fulfill their contract. That’s what basically happened to Rambo.

7. Thinking Cinematically

|

TR: The pacing of the Rambo cartoon is very intense. And when you add that classic Jerry Goldsmith score behind it, each episode feels like a mini-movie.

MC: That’s exactly what it was. The thing that made Rambo so unique is that it was an entire movie format shrunk down to 22-minutes, with none of the exposition. So it was all of the action from a movie! And the cool thing was, we could write stunts and gags that you couldn’t do in movies at that time! It would be either too expensive or too ridiculous. We could have Rambo jump out of an airplane, and float through the air and land on another plane. A lot of the stuff that we did in the pilot ended up in the third movie.

TR: I noticed that. There’s a tank scene in the cartoon that plays almost exactly like the climax of the film Rambo III.

MC: Right, and the helicopter scenes too. The thing that’s fun about animation is, when you’re the head writer, you have to be more than just a writer. You have to be a director and a cinematographer, because you have to call out all the angles and call out all the shots so that the storyboard artists can get it down correctly. So working in animation was a great learning experience for me. It taught me how to direct and how to think cinematically.

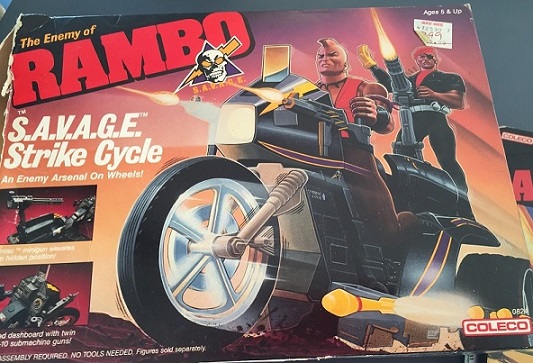

TR: The Rambo toys were a big part of the marketing behind the show. Can you talk about that?

MC: Well, I was given a set of villains, a set or heroes, and a group of toys. And the idea was to do whatever we wanted as long as the toys got shown. This was a huge toy project. There was a ton of money involved in toys and promotion. I mean, there was so much fun stuff. They created a whole line of Rambo forts, and Rambo trucks and weapons and figures. When you’re making toys, it’s all about what has good play value for the kids. So I basically had cart blanche to do anything I wanted. And since I hired a team of fabulous writers for the show, we were able to do some amazing stuff.

TR: What do you think it is about Rambo as a character that makes him so iconic?

MC: It’s a strong morality tale. Rambo is kind of like the samurai heroes from Japanese films, or the Kung-Fu heroes in Chinese films. He’s a symbol. He’s a lone man fighting for justice. He’s a good guy, who’s also an outcast, fighting against great odds all by himself. And that’s something powerful that appeals to a lot of people. It gives you the feeling that you can actually make a difference. And that’s the thing about Rambo that made him work. He was brave, he was strong and he fought for right. And he made a difference.

—-

Jack Bornoff is an actor, writer and story editor who worked on cartoons like Centurions, MASK and Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos. Here he discusses writing his favorite episodes of Rambo: The Force of Freedom, and why the show remains such a memorable experience.

8. Tracking the Beat Sheets

|

| Jack Bornoff |

Topless Robot: Were you a fan of Rambo before you started working on the series?

Jack Bornoff: I hadn’t read the book, but I’d seen the films. At the time, I’m not sure if there was more than just First Blood out or not. I was working in Chicago on interactive videodisk arcade games for Bally-Midway, and they sent me to Los Angeles to look for studio material that already existed and could be edited into games. So as I was searching for material, I hooked up with Ruby-Spears. And while I went through their library, they asked me if I’d be interested in coming out here and working on an action adventure show they were doing. They didn’t name it at the time. It wasn’t until later that I found out it was Rambo.

TR: You wrote quite a few episodes of Rambo. Did you have to pitch each individual idea to Ruby-Spears, or were you and Mike Chain given carte blanche to come up with the plots?

JB: Well, I was the assistant story editor on the show, so I’d meet with Mike Chain and we’d discuss a story idea, and at that point we already knew how many beats we needed per act. So I’d typically go in with a beat sheet, and I’d have five beats for act one, five for act two, five for act three, and we’d discuss them together. That included the messages that we included at the end of each episode. There were these little tags as the end, like moral lessons. And then I’d go to work if I got Mike’s script approval. Initially, we sent a few scripts to Joe Ruby’s office and they’d go through them, because there was a huge concern about Peggy Charren and the Action for Children’s Television group. She’d gone to Congress and complained about violent TV shows, and it was largely based on G.I. Joe. So before we started Rambo, Joe Ruby assigned me to watch a bunch of G.I. Joe episodes and keep track of what was considered violent content so we could avoid that kind of trouble.

TR: What type of things were you looking for?

JB: Oh, things like a helicopter goes down, and smoke comes out, but you never see the pilot get out. I learned that you could hit somebody, but it wasn’t considered violent if the person was a robot! There were all these strange subcategories of behavioral ethics! :laughs: In the long run, we were able to do some pretty creative things on the show.

9. Toy Money

|

| eBay |

TR: It’s interesting that the Rambo series began by staying very faithful to the realistic tone of the films, but became almost pure science-fiction by the end of its run, with freaky characters like Doctor Hyde and X-Ray appearing as villains. What was the thinking behind that change?

JB: Coleco was continually developing new toys and testing them in the marketplace. And since they were working on the Rambo figures and vehicles, one of the things that we ended up doing was introducing characters and things that they wanted to sell. So there are some bizarre twists and turns throughout the season, and they’re really based on the toy people who were paying the money.

TR: The job of a story editor often involves rewriting other people’s work. Did you and Mike ever run into any objections from writers whose work you changed?

JB: Oh, boy. I do remember every version of that you could think of! We had a couple of studio writers who’d been writing relatively soft kids shows like Alvin and the Chipmunks, not adventure shows like Rambo. And these writers really wanted to change their creative profiles and get some action credits under their belt. And at times it was a real challenge trying to help them with the process, which included starting with their beat sheets to help them grow into an action writer. It’s such a different skill-set, you see. So that meant polishing their scripts. For the contracted writers who came from outside the studio, they were solid action writers already. We could just hand them the show’s bible and they’d come up with a ton of premises that we could choose from.

10. A Message From Japan

|

TR: One of the episodes of yours that really stands out is called Enter the Black Dragon. It incorporates a deadly ninja villain, and at times plays out like a genuine martial arts movie. Can you talk about writing that episode?

JB: I remember working on all of the martial arts episodes because I have a martial arts background! At the time I wrote that, I’d been in the arts for twenty years. So I was really focused on including martial arts into the show. It seemed very fitting because Rambo often acts like a lone Ronin. He’s almost a Japanese samurai in America. So those episodes were a lot of fun to write. I got tremendous feedback from our director, who’d been in Japan when the Black Dragon episode was being storyboarded. Apparently the Japanese artists just loved it! They really loved working on that one in particular. They sent back a message that they really appreciated the authenticity of the script. That was very nice to hear.

TR: Are there other episodes that you worked on that stand out as particularly memorable?

JB: There was one I wrote called Subterranean Holdup that I really enjoyed working on. It was particularly fun because, as I mentioned, I came from Chicago. And subsequently, it was discovered that they built service tunnels under Chicago in the 1800s that were closed off and forgotten. Then, when there was a flood, those tunnels became apparent. But up until that point they were basically a secret. So I decided to write a Rambo script about a robbery of Chicago’s Federal Reserve Bank, where General Warhawk goes through those underground tunnels to steal the money. That was a fun one for me to do!

TR: Were there certain characters that you enjoyed writing more than others?

JB: I enjoyed writing Kat, because she had such a unique voice. It’s interesting because she’s a female character in what was basically a male cartoon world. So she was fun to write for. I also enjoyed writing Rambo too, particularly when he was talking with kids. At the time I was working on the show, I had a son in first grade. So when I’d pull up to his school, all his friends would shout “Oh look! That’s David’s dad!” because they knew I was on the show. So I felt a lot of responsibility to portray Rambo’s relationship to kids in an honest way that the children who were watching would respect.

TR: Looking back now on Rambo: The Force of Freedom, what’s your overall memory of working on the show?

JB: It was totally consuming. And none of it was negative. It was probably some of the best writing and most creative time I’ve had in my life. I was surrounded by a passionate group of talented writers. Being able to share the experience with my peers, because we shared offices on the floor, was a thrill. Having the support of Joe Ruby and Ken Spears was amazing. They were incredible people to work for. I’ve had two once-in-a-lifetime jobs in my career: The interactive videodisk arcade game job. And Rambo. I hope everyone in their lifetime gets to experience something in their workplace and their professional career that is as rewarding to them as this was to me.

Previously by Matthew Chernov:

10 Revelations From the New ‘He-Man’ Soundtrack Producers

10 Things We Learned From the 1986 Transformers Movie’s Original Cast & Crew