7 Surprising Ways the Original Oldboy Manga Differs From the Korean Film

|

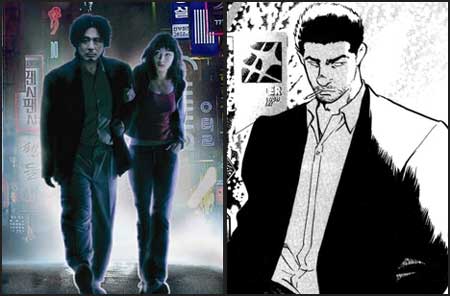

Here we are on the cusp of Spike Lee’s all-new version of Oldboy, which promises to be an intriguing new spin on Park Chan-wook’s internationally renowned revenge thriller [watch for the review coming later today – ed]. Instead of Choi Min-sik grasping a hammer and looking dangerous, we’ve got Josh Brolin to look forward to, while Sharlto Copley steps into shadowy antagonist Yoo Ji-tae’s shoes. But the trajectory of this new film version has some interesting curves to it; before Lee and Brolin got the project off the ground, the principals were director Steven Spielberg and actor Will Smith. This earlier take, Smith said, would be an adaptation of the original manga, and not the Park film.

But really, you’re wondering, how different could they be? In broad strokes, film adaptations of comic books are often pretty faithful to the source material. They kind of have to be, or it places the appeal of the original, a major hook for getting people into the film, at risk. But what Park Chan-wook accomplished with his 2004 Oldboy, when compared to Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi’s manga, is a startling piece of work: a film that faithfully reproduces the style and circumstances of the original, but with a more bluntly menacing tone and some very different story elements. Let’s have a look at nine ways Park’s Oldboy is a very different animal from the original manga, and how that might reflect on Lee’s film. Obviously, this thing is going to be full of tantalizing spoilers; if you want to experience these twists without your mind expectantly searching for them, go to Dark Horse Comics and grab the manga from them.

9) The protagonist is jailed for fifteen years instead of ten

|

In Tsuchiya and Minegishi’s Oldboy, we meet Shinichi Goto, a 35-year-old man who’s abruptly released from a shadowy private jail after a decade of unexplained imprisonment in a tiny room, with only a TV to keep him company. His counterpart Oh Dae-su comes out worse for wear – he seems a bit older when he’s pulled off the streets and jailed, and is locked up with the tiny TV for fifteen years to boot. Each man is in excellent physical condition on release, but Oh is noticeably older and more worn. While Goto is able to re-orient himself and grabs some temp work at a construction site to get some stability back, Oh wanders the streets, in isolation for so long he’s barely able to talk to people. It isn’t until a homeless person hands him a phone and a wad of cash that he’s able to seriously start hunting for the reasons why he was locked up. By the time Goto encounters a similarly-equipped hobo, he’s already pulled himself together.

8) The hero’s wife is murdered instead of his fianc?e being left at altar

|

The circumstances of Goto and Oh’s life before the kidnapping and imprisonment are also pretty different. Goto leaves behind a seemingly successful life and a pretty fianc?e at the altar. Oh is married and celebrating his daughter’s birthday the night he’s kidnapped, but he discovers, soon after his imprisonment, that his wife has been killed and he’s suspect #1. This changes the circumstances of their release – Goto is able to return to something vaguely approaching normalcy, as his fianc?e has long since given up on him and married someone else. Oh, on the other hand, has two big problems: he’s curious about what happened to his daughter, but he has to keep a low profile or he might be pulled by the cops for some uncomfortable interrogation room chit-chat about a long-unsolved murder.

7) The protagonists’ motivations don’t match up

|

Oh is released to life as a fugitive, with no connection to his long-lost daughter; he’s furious about what his captors did to him, and bent on finding not just answers but revenge. Goto also bursts out of jail spoiling for a fight, but the sudden intrusion of the real world sobers him up quickly. He accepts his circumstances, and starts casting about for a way to get back into society. He still seeks answers, not out of a need for revenge, but thanks to burning curiosity – curiosity that’s fed by his tormentor, who slowly reveals himself to Goto over the course of the manga.

6) The Korean film is way, way more violent and lurid

|

Here, let me lay this on you: in the original Oldboy, nobody dies. At least, not until right at the end, there. Contrast with the death of Oh’s buddy at the Internet caf?. The fights are less brutal, and the antagonist’s reasons for tormenting our lone hero are almost entirely psychological, and not based on a twisted little story of incest. Despite, that, the two works still have a strangely similar feel; Park’s shots of narrow streets, dive bars, and smoky neon lights are incredibly evocative of Shinjuku Golden Town, the real-life neighborhood where the Oldboy manga takes place.

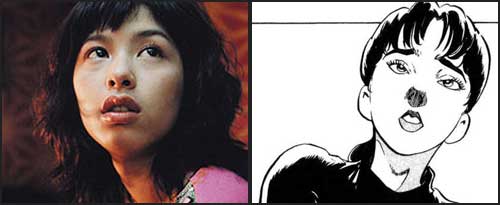

5) The hero falls in love with a young girl – but it’s not the same young girl.

|

…and that also contributes to the manga seeming much less oppressively brutal than Park’s film. In the film, we watch as Oh takes up with the young sushi chef Mido, and ends up starting a romantic relationship with her – which is made all the more shocking when Oh’s nemesis, Mr. Lee, reveals that she’s really his long-lost daughter, cementing his vendetta against Oh. In the manga, Goto is similarly taken in by a pretty young bar hostess named Eri, but there’s no prior relationship. We gradually discover that Eri is another pawn set up by Goto’s nemesis, a man who calls himself Dojima.

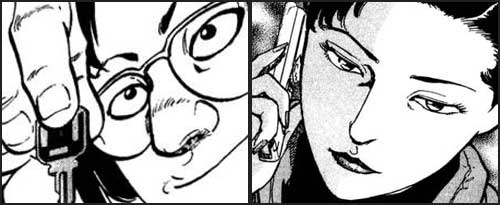

4) Some other important characters are very different.

|

Not long after getting out of the private jail, Goto seeks out his old friend Tsumakoto, who’s now running a charmingly cramped little one-man bar called MOON DOG. Tsukamoto keeps his old pal’s feet on the ground; he arranges a meeting with Goto’s estranged fianc?e, so the pair can have some closure, and since Goto doesn’t have a permanent address, Tsukamoto is happy to let him crash at the bar, in exchange for some occasional bartending and cleaning up. Tsukamoto is a tiny bit similar to Oh’s friend who runs the internet caf?, but while that character met with a swift and bloody end, Tsukamoto doesn’t. I’m very glad for this, actually; one of the strengths of Tsuchiya and Minegishi’s manga is that it makes goofy working stiffs like Tsukamoto and Eri really interesting and likeable. As the story progresses, you’ll find yourself worrying about their fates as much or more than Goto’s.

Then there’s Mr. Han, assistant to the shadowy and malevolent Mr. Lee. Our analogue to Mr. Han, on the right, is never actually named in the manga. We only learn that he was once a cleaner for the highest levels of the Japanese government, now under the private employ of Dojima. We never see Mr. Han getting into lengthy conversations, but his unnamed counterpart spends enough time stalking and shadowing Goto that they get to know each other pretty well. Eventually, when Dojima’s obsessions seem openly dangerous, his unnamed assistant starts quietly looking for a way to end things, with or without the bad guy’s consent.

3) Other important characters don’t make it into the movie at all.

|

Goto eventually confronts Dojima, the man who locked him away from the world, but doesn’t recognize the guy. Dojima, relishing the awkwardness and tenseness of it all, starts feeding Goto hints. As Goto searches more extensively for the story behind his tormentor, Dojima imposes a rule – if Goto discovers his identity and why he hated Goto so much he locked him up within a certain time frame, he’ll kill himself. But if Goto can’t make the deduction in time, his life will be Dojima’s to do with as he pleases. To enforce this fiat, Dojima dispatches a referee, an ingratiatingly nerdy man who shows up at the bar, feeds Goto clues, and tries to draw out the contest as long as possible. He’s an amusing little side character, kind of an otaku type, and there’s no analogue for him in Park’s film.

Shortly thereafter, Goto determines that Dojima is an old classmate of his, and the ref suggests he contact their old schoolteacher, Yayoi Kusama. She was young when she taught them as grade schoolers; in the intervening years, she left teaching under harsh circumstances and became a mildly successful mystery writer. She agrees to meet Goto, and while she can’t immediately recall his secretly antagonistic classmate, she’s roped right into the story. This is all by Dojima’s design; he’s pulling some strings to keep her busy, and knows that her nature will compel her to not just aid Goto, but to start documenting the entire mess. Again, Park can’t find a spot for her in the film. It doesn’t diminish the film, but it adds to the flavor of the manga.

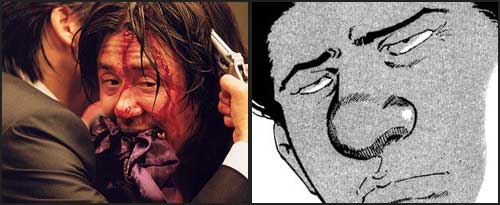

2) The protagonist is left as damaged goods, but in very different ways

|

Oh Dae-su cuts out his tongue in an act of penance to Mr. Park, whose life he’d ruined by inadvertently gossiping about Park’s unseemly familial activities. He spares Mido the torment of knowing she’d hooked up with her dad, and hires a hypnotist to try and help himself forget. He’s permanently disfigured, and tormented. Shinichi Goto doesn’t go to these extremes, but late in the game he discovers that both he and Eri have undergone a deep, pervasive program of hypnosis to ensure that they’d play along with Dojima’s game. He and Eri leave Dojima and his cruel game behind, but he finds himself plagued by nightmares and doubts; what if Dojima left one final savage twist for him, hidden in Eri’s impressionable young mind?

1) There’s no hammer fight.

|

Yep. Read that again: there’s no hammer fight. No incredibly, almost hilariously epic hammer fight. The signature moment of Park’s film, the breathtaking long-take action scene that almost surely cemented it as an international sensation, the best part of the movie, the bit that you can clearly see Josh Brolin aping in the American Oldboy trailer – is entirely missing from the original manga. I told you guys, it’s just not as violent. In fact, Goto’s entire discovery of the private jail building is a lot less savage. He meets and incapacitates the jailer, but there’s no tooth-pulling, no stabbing, and no one-against-ten brawl. And more than anything else, that sums up the differences between Park’s film and Tsuchiya and Minegishi’s manga. One is a tale of bloody revenge, while the other is a longer game, a potboiler of a story about mystery, suspense, and an unanswered grudge.

So in the end, while Park Chan-wook created a superb re-imagining that successfully captures the style and part of the story of the original, its tone is markedly, wickedly different. This is actually pretty great, because it means that both the Oldboy film and the Oldboy manga are essential stuff, hugely compelling and suspenseful, but for entirely different reasons. This leaves us with the question: which is more essential? The answer to that is obvious: it’s stupid to add a modifying adverb to superlatives.

Okay, what’s my real answer to that tough, tough question? It’s gotta be Park’s film. The manga’s very important, since it led to the film, but the film is a stark, beautiful piece of work that snaps its many pieces together perfectly and leaves us one big question: is Oh Dae-su gonna survive the consequences of his terrible, awful revenge? The manga, much more subdued, is content to let more threads dangle. As we gird ourselves for the new Oldboy film, I only hope that it gives us yet another angle to contemplate how far a man will go to get his revenge – or what lengths he’ll go to in order to satisfy his simple, inescapable curiosity.

One final note: if you have read all of the Oldboy manga, you might protest that I’m not using all the correct names, or that I didn’t mention this or that. Yeah, you’re right. I didn’t spill all the beans, and that’s because I want the newbies who couldn’t stop themselves from reading this whole article to still find lots of great stuff to read in the manga. The entire 8-volume series is available from Dark Horse, and I urge you to read it without delay – for comparison’s sake, it’s like a slightly more realistic version of the kind of story Naoki Urasawa (the 20th Century Boys and Pluto guy) would cook up. Check it out!

Previously by Mike Toole:

Ten Crazy Korean Cartoon RIpoffs

Nine Celebrities Who You Probably Didn’t Know Voiced Anime Before Princess Mononoke

Ten Crazy Things from the Original ’70s Gatchaman Cartoon We Hope to See in the New Movie