The 8 Best Side Effects of the Power Rangers

|

By Todd Ciolek

For some reason, the Power Rangers franchise has yet to find

its way into the upper echelons of cherished childhood memories. Perhaps the

generation that grew up on Megazords and Rita Repulsa is still too young to get

nostalgic and buy the show in convenient DVD box sets. Perhaps the constantly changing

Power Rangers series and characters make it hard for an entire nation of kids

to attach themselves to Green Rangers as they might idolize Goliath or Dinobot or

Pikachu. Perhaps Power Rangers is, in all of its forms, a really terrible thing

and every kid realizes that upon turning eleven.

Let’s set aside the question or whether Power Rangers is

under-appreciated or worse than Stunt Dawgs. Even if Power Rangers were

terrible, the popularity of the show still brought about many beneficial

effects back in the 1990s. And now, as the Power Rangers juggernaut possibly takes its final lumber through toy aisles and Disney-owned syndication deals everywhere, let’s

take a look at just what it did for pop culture.

8) It Promoted Even More Ridiculous Japanese Live-Action Stuff

As young fans of Mighty

Morphin’ Power Rangers learned sooner or later, the 1990s series is a

Japanese show re-dubbed and spliced with new footage to make it palatable to

American sugar-cereal-feeders. Those who dug deeper found that Power Rangers is part of a long

tradition of “super sentai” shows, which in turn are part of the entire

Japanese tokusatsu school. Wikipedia defines tokusatsu as “live-action Japanese

film and television dramas that generally feature superheroes and make

considerable use of special effects.” A more apt description would be “grown

men running around in spandex costumes while fighting giant puppets and people

in monster suits, all framed by effects that would’ve been low-budget by 1970s Doctor Who standards.”

Yes, tokusatsu movies and television are often marvelous

camp, and Power Rangers introduced many children to this world of rubbery

aliens and stiff robots and complete cheese. Most kids see a Godzilla movie or

two while growing up, but Power Rangers made tokusatsu into flashy, coveted

lunchbox-cover material. And even after the allure of Power Rangers faded,

those kids were more likely to notice Japan’s silly superhero and monster exports,

whether they were Godzilla: Final Wars,

the old tokusatsu version of Spider-Man, or just some sentai-hero moments that

were a little too extreme for American TV. Moments like this:

7) It Brought Back Good Ol’ Irony-Free Violence

During the 1980s, the likes of Transformers and G.I. Joe

played up action and conflict to the point where the animation industry got a

little sick of it. As the decade closed, the most popular cartoons were comedies

and lighthearted adventures, including the often limp satire of Tiny Toon Adventures and the filthy

capitalist escapades of Duck Tales.

Even the Ninja Turtles punctuated their battles with a repertoire of self-aware

quips. Kids had Batman: The Animated

Series by 1992, but Batman was familiar territory. Kids wanted something

new.

Well, they got that with every Power Rangers episode. It

looked like Saved by the Bell with

its Archie-esque drama mixed with clips of a Japanese superhero series, but it

had plenty of violence.

Bloodless and really stupid violence, but it was still

violence without any cutesy Disney cop-outs or sarcastic one-liners to break

the fourth wall. Just punching and kicking and other things that you could

easily imitate on the playground.

6) It Made Parents Accept Pok?mon and Dragonball Z

Parents, teachers, and child psychologists grew to hate the

Power Rangers. It wasn’t just the violence, either. In the flailing battles

between the Rangers and various garish-colored creatures, the older generation

saw the many hokey monster flicks of their childhoods, and they decided that

they weren’t going to let their own spawn be won over by something with even

dumber stories and more aggressive marketing. Most parents didn’t complain about

Power Rangers any more than their own parents had scoffed at Speed Racer or the latest from Sid and

Marty Krofft’s House of Abominations, but everyone was clearly relieved when

the Power Rangers hype eventually died down and gave way to another Japanese import:

Pok?mon.

Never mind that

Pokemon was Nintendo-sponsored cartoon cockfighting. Pokemon had cuddly animals and a theme song about teaching each

other some semblance of morals. Heck, even the Vatican approved of it. This

parental attitude applied to other Power Rangers successors, including the

considerably more gruesome Dragon Ball Z.

For some reason, the PTA is less likely to throw a bitchfit over pure nonsense

and rampant violence when it’s animated.

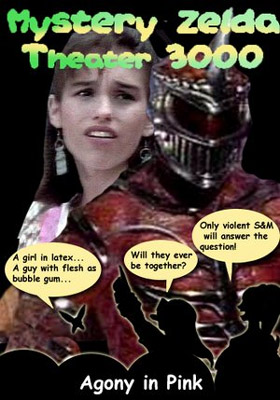

5) It Helped Show Everyone How Awful Fan?Fiction?Could Be?

|

?at Topless Robot, we strive to explore the depths to

which modern fan-fiction can sink. However, there was a time when fan-created

stories weren’t held up to widespread mockery; they were kept within the pocket

online communities that specialized in writing and giggling over stories about Goku

kissing Captain Picard. The more level-headed of us were bound to encounter

truly disturbing fan fiction sooner or later, and by chance most encountered it

through a notorious tale called “Agony in Pink.”

The story first appeared on Usenet in 1994, courtesy of

someone known as The Dark Ranger. It can summarized as follows: the Pink Ranger

is tortured and ultimately murdered by a monster named Tortura who, needless to

say, was created exclusively for the narrative. It’s a disturbing journey

through graphically described sadism, and the fact that it’s all based around

Power Rangers makes it both disquieting and laughably absurd. In the 15 years

since its publication, “Agony in Pink” has become a touchstone for all terrible

fan fiction, and it’s even the subject of artwork and amateur MST3K treatments.

It’s easy to find all sorts of uproariously bad fan fiction

nowadays, based on anything from Mr.

Belvedere to Swat Kats, so it’s

hard to remember that “Agony in Pink” once shocked or stupefied anyone. But it

did.

4) It Brought Children Together

Let’s face it: most of the respectable children’s shows of

the 1980s and 1990s didn’t really inspire followings as much as the mercenary

ones. Duck Tales never had kids

arguing over who got to be Uncle Scrooge, but He-Man and every toy-shilling series after it was packed with

characters that impressionable youths could imitate, arguing over who got to be

Man-At-Arms and who was saddled with the Orko role. This tradition faded in the

1990s as the Ninja Turtles fell in popularity, but Power Rangers brought it all

back.

Once again, grade-schoolers could bicker over their favorite

roles from a TV show, and they had at least six color-coded parts to assign. Unlike

the majority of action-oriented kids’ shows, there was more than one character

for girls to emulate in schoolyards everywhere (yes, the yellow ranger was male

in the Japanese version, which for some kids was like finding out about all the

kittens that died to make Milo and Otis).

Even if you were delegated the part of the nerdy Blue Ranger, you could still

run around and demonstrate Power Ranger techniques until someone had to visit

the school nurse. And that’s what children’s shows are really all about.

Just as Teenage Mutant

Ninja Turtles gave rise to uninventive twaddle like Pre-Teen Dirty Gene Kung-Fu Kangaroos, Power Rangers had its

also-rans. The one difference: most of the Power Rangers rip-offs were put out

by the show’s handlers at Saban Entertainment, which wasn’t about to stop at

just one amalgamation of Japanese sentai superheroes and new American footage.

So the airwaves saw VR Troopers, Masked Rider, The Mystic Knights of Tir Na Nog, and this…thing.

Of these Power Rangers clones, VR Troopers and the even more insipid Beetleborgs proved the most enduring, as Saban desperately tried to

find more inexpensive and unrelated Japanese shows to cut-and-paste into

American properties. One has to feel a little sorry for Masked Rider. It’s a late-1980s sample from the Kamen Rider franchise, which has legions

of TV series, films, and toy lines to its name in Japan. In North America, however,

it lasted only half as long as a show about Goosebumps

brats turned into metallic roaches by a spectral, blue-faced Jay Leno.

2) It Inspired Some Great Parodies

Mocking Power Rangers and the broader world of sentai shows

is a little too easy. Stick characters in colored outfits, throw them in a

robot, start the discount fireworks, and you’re a champion of satire. It’s been

roasted to death in Japan’s cartoons and live-action shows for decades, and

most of these take-offs are downright lazy. A few are amusing, though, and a

brief anime series called Shinesman stands

out among the better ones.

Shinesman is a

parody of sentai run through the Japanese salaryman aesthetic, with a young

go-getter chosen as the leader of a superhero combat team just because he likes

the color red. Armed with sharp-edged business cards, his fellow armored Power Rangers

look-a-likes include Shinesman Gray, Shinesman Salmon Pink, and Shinesman

Sepia. Yes, it’s contrived and obvious comedy, but it’s saved by a rather

liberal approach to the English dub, which isn’t afraid to play up the

silliness of it all and invent some new jokes along the way (even if any and

all South Park references stopped being funny in 1999). And, unlike many

alleged anime comedies, Shinesman‘s

over before it can wear out its welcome.

As an hour-long comedy based on a much longer manga, Shinesman would have been made even if

Power Rangers had flopped in America. In fact, Shinesman might have been released in English even without any

Power Rangers pull, since its North American publisher, Media Blasters, bought

just about any cheap, short, direct-to-video anime in the late 1990s. Yet Shinesman and its dubbed treatment

wouldn’t have carried as much appeal without a cultural fixture like Power

Rangers for a target.?

1) It Got Kids to Love Giant Robots Again

Since the days of Gigantor,

robots have risen and fallen in favor among young American generations. After

reaching an apex of popularity with the Transformers

and dozens of imitators in the 1980s, robot-centric toys and cartoons slid out

of power, dethroned by the Ninja Turtles and, shockingly, cartoons that weren’t

even built around toy properties.

Power Rangers smashed these idols of taste and artistic

value. The Rangers had giant robots that formed an even more giant robot to

combat equally giant monsters, and all of them were perfect for toys. Voltron had done the same thing for

children of the 1980s, but it was never the toy-department wonder that Power

Rangers was. Kids could get figures of the Power Rangers, the various

creatures, and, most importantly, the huge megazord mecha and its ultrazord

accoutrements. And they would break through the load-bearing walls of your

home.

These robot dinosaurs and apes helped rally other

mecha-based toy lines back to the front. In the years after Power Rangers

became huge, Transformers returned

with Beast Wars, and even Voltron came back with a CG remake. It

may be Voltron that’s remembered in

the West as the quintessential giant mecha piloted by a team of kids, but it’s

Power Rangers that reminded everyone why kids loved big robots.