6 Excellent Tabletop Role-Playing Games with Atypical RPG Settings

|

?Tabletop RPGs seem to have fallen by the wayside in recent years, their position usurped by the phenomenon of online gaming. Titles like World of Warcraft and Star Wars: The Old Republic to name a few, are the order of the day. I find this rather sad, frankly. I know I’m showing my age, but time was if you wanted to build your own character and participate in adventures inside a rich and detailed fictional universe, you had to get off your ass, visit some friends, and accumulate an absurd amount of oddly shaped dice.

Now, you don’t have to be a gamer, or even a nerd to know the granddaddy of the tabletop RPGs is Dungeons & Dragons, but fantasy adventure is hardly the last word in role-playing. Most geeks are at least aware of popular games like the superhero-based Champions, the cyberpunk/fantasy crossover Shadowrun, and White Wolf’s World of Darkness games like Vampire, Werewolf, and the rest. Furthermore, pretty much every nerdy franchise of note has had a tabletop RPG made for it: Star Wars, Star Trek, Doctor Who, Transformers, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and both Marvel and DC Comics have all had their own role-playing games at one time or another.

But what about other tabletop RPGs? Those games that aren’t visit the traditional RPG worlds of fantasy, cyberpunk, superheroes, or the occult? The ones that aren’t based on any pre-existing fiction? Here’s six RPGs with “non-traditional” RPG settings that are just as great as any of the big boys. Obviously, some hardcore role-players will be intimately familiar with these, but to the rest of you, I highly recommend checking them out!

6) Noir

|

?The “film noir” setting got a little bit of love in the well-known Call of Cthulu games based on the Lovecraft mythos, and has occasionally been an alternate campaign setting for other games (there’s a “Discworld Noir,” for example), but the genre itself wasn’t explored for its own merits as an RPG setting until Jack Norris, Brian S. Roe, and other associated writers developed Noir for Archon Gaming, Inc. The game runs off a simple six-sided die pool system — combat, performance of tasks, and character creation are all fairly straightforward. Character Archetypes/Classes (called “Schticks”) run the gamut from the general (Athlete, Troubleshooter), to the more genre-specific (Private Eye, Torpedo, Femme Fatale). All in all, it’s a pretty basic game with a great deal of room for GM imagination — e.g., the included campaign setting is called simply “The City.”

5) Traveller

|

?While there are plenty of sci-fi RPGs, most of them are based on established properties, and the rest tend towards the cyberpunk. Weirdly, there aren’t a lot of original hard sci-fi RPGs out there — although one of the oldest and best-known is Traveller (yes, with two Ls). Traveller has had numerous sequels and iterations since its first release in 1977 by Game Designers Workshop; indeed, game designer Marc Miller’s original concept was simply “Dungeons & Dragons in space.” The current version of Traveller was published by Mongoose Publishing in 2008, and is one of the most complicated RPGs you’re likely to run into. Character creation is especially detailed, using a unique “Lifepath” character generation system that’s almost a game in itself. The prospective player rolls 2d6 (two six-sided dice, for the “RPG-challenged”), and his or her results determine such things as what kind of childhood they had, their level of education, hobbies and interests, phobias or neuroses, work experience, possible legal problems, personal relationships, etc. Bottom line: Better set aside a session exclusively for character creation, ’cause making four characters and starting a campaign in the same night ain’t happening. The game setting itself is a relatively generic, human-centric (aliens exist, but are not covered extensively in the core book) interstellar society called “The Third Imperium” (the overall feel is similar to Firefly‘s “Union of Allied Planets”). Focus is much more on characters and how they relate with each other and NPCs (non-player characters) than on the setting and its trappings — another aspect that makes Traveller unique in an RPG genre that’s all too often rather superficial.

4) Pendragon

|

?Imagine D&D for history and mythology geeks, and you begin to get an idea of what Pendragon is. Created by Greg Stafford for Chaosium (originally), Pendragon is not a fantasy adventure game per se — magic is rare, and usually more trouble than it’s worth to PCs, and non-human foes are even rarer. Rather, it’s based on Arthurian legend, and is focused primarily on playing knights in the Age of Chivalry. Granted, this does limit one’s role-playing options a bit; 2008’s 5th Edition added the supplement The Book of Knights and Ladies, bringing a bit more diversity to the game, and there are alternate rules if one wishes to play in a more fantastical version of the setting. Character creation is more complex than D&D (though not Traveler complex) and uses a variation of the “Basic Role-Play” (BRP) system, as does gameplay. Most unique is Pendragon‘s focus on the character’s family: There are multiple tables for determining what happens to one’s spouse and children while one is out performing their knightly duties. You can even end up playing as one of your children or grandchildren after your first character is slain!

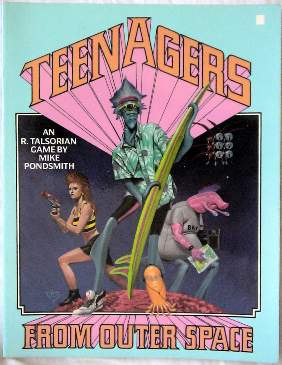

3) Teenagers from Outer Space

|

?Absurdly simple in both character generation and game play, Teenagers from Outer Space is a semi-parody of anime and manga tropes. Created by Michael A. Pondsmith for R. Talsorian Games, back in 1987 when anime and manga were still largely a cult phenomenon in the West, the latest edition (1997) was slightly retooled to play up the tropes a bit. The concept is pretty simple; aliens have made contact with Earth, get subsequently enchanted by human teen culture, and begin sending their own kids to high school here. Players can take the roles of human teens, but more likely they’d choose one of the aliens, which come in three basic flavors: Near Humans (think most common Star Trek aliens), Not Very Near Humans (think anthropomorphic animals), and Real Weirdies (anything not basically human-shaped). As mentioned, character creation and play are simplified — the most unique aspect is a mechanic called “Knacks”, which are abilities the player invents, which can essentially be anything the GM will allow. Examples given include: “Drive Like a Maniac,” “Fire Raygun,” and “Avoid Being Harassed by Authority Figures.”

This was the first non-mecha-oriented, anime-related RPG to achieve success, and aspects of it would go on to inspire games like Big Eyes, Small Mouth.

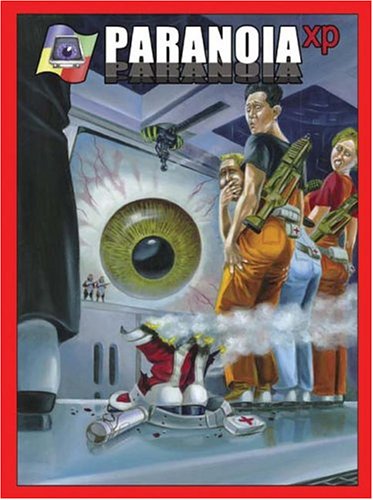

2) Paranoia

|

?I can’t say enough awesome things about this game (the only reason it’s not at the top of the list is I’ve never actually played it. I own it; I’ve just never found enough people interested in playing). Originally designed and written by Greg Costikyan, Dan Gelber, and Eric Goldberg, and first published in 1984 by West End Games, Paranoia is a wickedly satirical take on sci-fi dystopias, but more than that, it’s a scathing satire of the entire concept of tabletop RPGs in general, especially in its current iteration of Paranoia XP, first published in 2004 by Mongoose Publishing after West End went bankrupt (the “XP” was removed in 2005 at the behest of Microsoft).

Most RPGs stress cooperation between players: Paranoia encourages backstabbing and betrayal. Most games teach that the GM is the players’ friend, and there to help: Paranoia teaches that the GM is not to be trusted, and that he or she will do the best they can to undermine the players. Your average game has rules that do their darnedest to prevent character deaths: In Paranoia, a TPK (Total Player Kill) is not only possible, but commonplace. In any given game session, expect at least one character to die at least three times (players have six clones apiece… unless there’s an accident at the cloning facility…). The game mechanics and character creation are simple — a single 20-sided die is all you’ll need –and the best part is the “Dramatics” system: Essentially, actions attempted by a character that are especially absurd, entertaining, or outrageous can be given bonuses toward success.

Your goal in Paranoia is much more to entertain your fellow players and GM than to fulfill the Mission, which is assigned to you by the all-powerful, batshit insane Computer that runs the futuristic, underground civilization of Alpha Complex. This is complicated by the fact that these missions often involve finding illegal mutants or discovering illegal secret societies… as every single clone is a mutant and a member of a secret society, unknown to everyone else (and the Computer. Maybe). It’s also complicated by the fact that the Computer is more paranoid than anyone, doing almost anything in Alpha Complex is potentially fatal, and at least some of the missions are completely impossible. Again, Paranoia is much more about fun than silly things like “success” or “survival.”

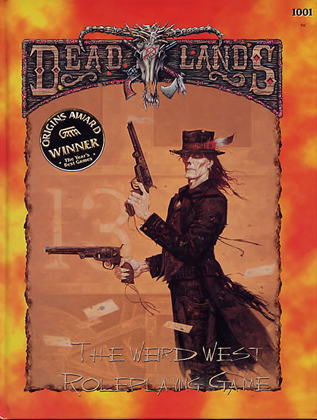

1) Deadlands

|

?Created by Shane Lacy Hensley for Pinnacle Entertainment Group, Deadlands is a wonderful mix of genres: Wild West plus alternate history with a supernatural edge and a dash of steampunk — the resulting tapestry is known in the game as “the Weird West.” It’s 1876, and history as we know it is the same up until July 3rd, 1863 — when a group of Sioux led by the shaman “Raven” opened a conduit to the spirit world in an attempt to drive out the white settlers. This act released malicious entities known as “Reckoners” — evil beings which feed on human fear and are bent on creating hell on earth. Wherever there is enough fear, the Reckoners can alter our reality — bringing about monsters and apparitions, and possessing both the living and the dead. The Civil War drags on due to the machinations of the Reckoners, while technological achievements that defy logic are possible thanks to them. Characters include Archetypes like Gunslingers and Lawmen, and wielders of arcane power like Hucksters (Magic-Users), Mad Scientists, Alchemists, and Shamans. The game has unique aspects like “fate chips” (poker chips that can be used as experience points, or for bonuses during game play) and a deck of standard playing cards for determining initiative and character creation along with the typical polyhedral dice.