Ten Movie and TV Characters Named Insultingly After Real-Life People

|

The vendetta is one of the privileges of creating fiction. When you’re the Supreme Being in the world you’ve created, you’re free to visit misery upon those you resent, and you can make the villainy you see in them unmistakably visible to others.

Of course, plenty of authors, screenwriters and directors have spent their whole careers expressing their misogyny, misanthropy, nationalism and other bigotries through their work, sometimes not quite consciously. But there’s a coarser, more specific, more childishly fun exercise of this power: Naming a character that’s either reprehensible or doomed (or both) after somebody you hate. Critics, as we shall see, are favorite targets of this.

Then there are times when such a naming doesn’t seem to have been intended with conscious malice, but is potentially insulting anyway, as in our first example…

10. Michael Myers from Halloween (1978)

Along with the chalky deflated-Shatner mask and overalls, the slasher genre’s generic boogeyman in John Carpenter’s signature chiller bears a similarly prosaic name: Michael Myers. He got it from a British film mogul who had helped handle the European distribution of Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976). It doesn’t appear to have been intended as a reflection on the man’s character, but the original Mr. Myers might still have been taken aback by the peculiar honor. Then again, Carpenter is also said to have named his terrified, traumatized heroine, Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), after his first girlfriend.

And then there’s the matter of “Ben Tramer,” the much-discussed boy that Laurie’s interested in. He was named in honor of Carpenter’s old crony Bennett Tramer, later a producer and writer on Saved By the Bell. He remains offscreen in the first film, but in Halloween II (1981) he becomes perhaps the most indirect and incidental victim of Michael’s killing spree. So being the namesake of a Carpenter character may feel like being on the receiving end of passive-aggression.

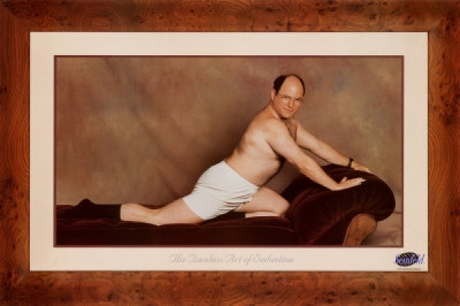

9. George Costanza from Seinfeld

|

The neurotic, self-sabotaging best friend of the title character in the legendary “show about nothing” (NBC, 1989-98), brilliantly played by Jason Alexander, was based on series co-creator Larry David. But his name came from a guy Seinfeld knew in college, Mike Costanza. In 1998 the real-life Costanza sued, on the grounds that nobody had asked his permission, and that the character made him look bad.

A cynic might speculate that the real motivation for the suit was the idea that the enormously lucrative show might throw some nuisance settlement bucks his way, but it didn’t work out that way. Here again, nothing suggests that Seinfeld disliked the guy, but after the lawsuit he probably liked him less.

8. Liane the Horse from Cannibal! The Musical (1993)

In this rollicking indie musical based on the case of frontier man-eater Alferd Packer, Liane is the name of Packer’s horse, whose disappearance leaves him bereft and unable to function. Reportedly Liane’s namesake was actress and dancer Liane Adamo, who was writer-director-star Trey Parker’s fianc?e until it was learned she was having an affair. This gives another level to some of Parker’s lyrics, as when Packer, lamenting his mount’s absence in the wistful number “When I Was On Top Of You,” sings:

I’d pull her hair

And she’d know to stop

And when she’d look behind her

I’d always be there…

Liane is also said to have supplied the first name of Cartman’s mother on South Park.

7. Mikey and Nicky from Mikey and Nicky (1976)

7-A and 7-B are the two title characters in this excellent, too-little-remembered gangster picture from writer-director Elaine May, and it’s hard to believe that they weren’t jointly named in honor of May’s old improv partner Mike Nichols. Nicky, played by John Cassavetes, is a wound-up gangster trying to elude a hit man (Ned Beatty), while Mikey, played by Peter Falk, is the staid childhood friend to whom Nicky has turned for help; the movie is essentially another of those extended improvisational Cassavetes-Falk duets (all that’s missing is Ben Gazzara). Their riffing didn’t always amount to as much as they seemed to think it did, but here it’s tense and funny and troubling.

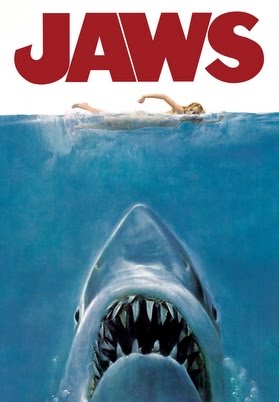

6. Bruce the Shark from Jaws (1976)

Though not so called onscreen, during production of Steven Spielberg’s breakthrough film the big robot shark – notoriously a “difficult” performer – became known by the crew as “Bruce.” This moniker was reported in the initial press coverage on the movie – even, if memory serves, in the pages of Famous Monsters of Filmland – and the name caught on with fans. Spielberg himself is supposed to have so dubbed the fish, after bigshot entertainment lawyer Bruce Ramer. It’s doubtful that this predates the familiar joke about why sharks don’t eat lawyers (professional courtesy), but it’s probable that Ramer was delighted rather than offended. After all, everyone knows that the best advertising is always word of, well, mouth.

5. Cypher, a.k.a. “Mr. Reagan” in The Matrix (1999)

If you’ve never seen the Wachowskis’ classic – which seems like a long shot, if you’re a regular reader of this site – then fair warning, I’m about to reveal a major plot point. Cypher (Joe Pantoliano), the turncoat among the rebels who wishes to return to the comfort of the virtual-reality “Matrix,” is referred to by the sinister Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) as “Mr. Reagan.” In case there’s any doubt about the reference, a few lines later Cypher says “I want to be someone important. Like an actor.” Between this and what can be presumed about the Wachowskis’ politics from, say, V for Vendetta or from having Cornel West appear in their films, it’s easy enough to spot a political allegory here, something like: After the ’60 and ’70s counterculture revealed the fraudulence of superficial mainstream society and our unwitting enslavement to consumerist corporatism, the Rise of Teflon Man in the ’80s took us back to contented ignorance. Or tried to, anyway. The Right didn’t count on a big-budget sci-fi movie blowing the lid off the whole thing.

4. General Kael in Willow (1988)

|

It may be that one of the signs of serious clout as a critic is when aggrieved filmmakers name a villain after you. The helmeted, masked heavy (Pat Roach) in this enjoyable, slightly underrated high fantasy from producer George Lucas and director Ron Howard is, of course, named after Pauline Kael, the Grand Empress of New Yorker reviewers, she of the contrarian dislikes and the whimsical pet favorites and the jugular-severing snark and, most maddening of all, the unassailably beautiful prose style. In her generally dismissive review of the film, Kael, who regarded Star Wars as a ruinous development in ’70s cinema, referred to the General’s name as an “hommage a moi.” But hommage probably isn’t the word that Lucas had in mind.

3. General Sarris in Galaxy Quest (1999)

According to IMDB, the nasty lizard-lobster-man played by Robin Sachs in this well-liked spoof of Star Trek carries the same name as Village Voice and New York Observer critic – and famed object of Kael’s disdain – Andrew Sarris, all because the scribe slammed GQ producer Mark Johnson’s 1984 baseball hokum-fest The Natural. But if I understand the auteur theory correctly – and it’s by no means certain that I do – Galaxy Quest seems like the sort of thing that an auteurist like Sarris might have approved of: a piece of big-studio Hollywood product by a journeyman director, Dean Parisot, out of which glimmers of eccentric personality may be perceived. In any case, “Sarris” fits the character; it has a nice hissy sound.

2. Mayor Ebert in Godzilla (1998)

|

The harried Mayor of the Big Apple in Roland Emmerich’s Yank entry in the Japanese monster franchise shared a name with superstar critic Roger Ebert, and was played by Michael Lerner, who bears a resemblance to the recently lamented King of the Extended Opposable Thumb. Hizzoner even had a loyal sidekick named Gene (Lorry Goldman).

If this was intended as flattery, it didn’t work; Ebert gave the film a near-pan, calling it “a big, ugly, ungainly device to give teenagers the impression they’re seeing a movie.” But more likely, given Ebert’s reviewing record of Emmerich’s earlier work, it was intended as a pre-emptive flip of the bird.

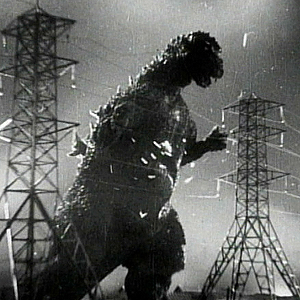

1. Gojira (1954)

|

Finally, there’s The Big G himself. The beastie’s name in the original kaiju film, before it was enriched with extra consonants for the American market, is said to be a blend of the Japanese gorira (gorilla) and kujira (whale). But according to The Official Godzilla Compendium, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka claimed – perhaps apocryphally – that it was originally the nickname of a Toho publicist of vast and lumbering girth.

Again, there’s no indication that Tanaka scorned this man personally, but still, being known as “ape-whale” can’t exactly be called complimentary, even if it makes you the namesake of one of the great pop-culture icons of all time.