The 7 Best Ways to Clear up Comics Continuity Errors

|

| Warner Brothers |

| Infinite Batmen from Brave and the Bold |

When you put them together, Marvel and DC have been publishing two continuous, multi-titled universes for more than 125 years. Trying to keep the rich histories of these books straight has been an uphill fight for the editors and the publishers, and it’s a common problem in genre fiction. The instant an author has to account for more than two people in more than one book, she runs the risk of losing track of one of them for long enough to trigger a flood of enraged fan mail.

Writers and editors have created a handful of tools to try and deal with the array of logistical problems that pop up in these situations. Comic companies, writers and artists (and editors and writers in countless other genres) have used these tools as shorthand to provide in-story explanations for screw-ups, as creative fuel for interesting stories, or as ways to try and channel that fanboy letter writing verve into more constructive arguments, like “can Wonder Woman fight in heels because her calves are superstrong, or because she’s constantly flying a half an inch off the ground so it only looks like she’s walking?” Here are 7 of the most commonly used tropes for streamlining continuity problems:

7. Infinite Worlds

|

| Art by Carmine Infantino |

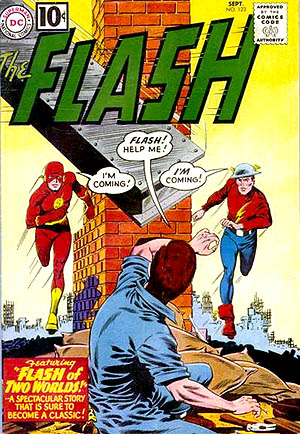

The first real attempt at unifying diverse comic universes was “The Flash of Two Worlds,” a 1961 story from DC that had the first meeting of the Golden Age Flash, Jay Garrick (from WW2-era comics), and his Silver Age descendant, Barry Allen. Earlier DC stories had casually mentioned that the Golden Age stories existed as comic books to the new-ish iterations, but the two had never met before. “The Flash of Two Worlds” set up DC’s parallel worlds structure, where the Golden Age heroes of the Justice Society were located on Earth-2, while the characters from the ongoing DCU were located on Earth-1. And thus was born the fictional shanghaiing of the Many Worlds theory.

This trope is used throughout fiction: sometimes to tell single stories (It’s a Wonderful Life), sometimes for character exploration (everyone on Star Trek with a goatee except Sisko is visiting from their Earth-3. Sisko with a goatee is just being more awesome) and sometimes to add a sense of epic scale to stories that might not otherwise have it, likeFringe.

In the DC universe, it became shorthand for explaining away continuity errors and integrating characters purchased from other companies – the Charlton characters (Blue Beetle, the Question, Peacemaker, etc.) existed on one Earth, while the Fawcett characters (the Marvel family) existed on another. Elseworlds, DC’s “What If” stories, also take place in discrete dimensions.

Marvel has distinct numbered dimensions going as high as Earth 989192, with many of them showing up through What If stories and a large number of them popping up through series designed to skip through the Marvel multiverse. Marvel also has the odd tendency of blocking off its lines – the X-books regularly interact with each other, but rarely with the rest of the MU; the same for Avengers or Spider-Man or the space comics. This makes the line feel like it’s happening on multiple worlds. Sure, Wolverine is in almost every comic, but he shows up on a story by story basis, and for anyone other than Jason Aaron, trying to write out the beats in his daily schedule is usually futile.

Marvel also has the Nexus of All Realities, a hillbilly Dark Tower. In Stephen King’s written universe, all fiction exists as separate levels of the tower, explaining why the Tower characters go through The Stand‘s Kansas and meet up with Pere Callahan from Salem’s Lot to fight bad guys dressed like Dr. Doom wielding lightsabers and snitches from Harry Potter. In the Marvel U, the Nexus of All Realities is a gateway to each of their almost-a-million dimensions, as porous as a shitty gas mask and guarded by a handful of Florida swamp people and Machine Man.

6. Infinite’s a Lot. What About “Several Worlds?”

|

| DC Comics |

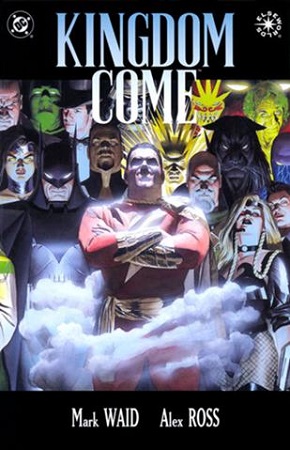

Because there’s apparently a cap to the amount of space available in the quantum multiverse, DC’s current continuity status is a “let’s not get too crazy” version of the infinite worlds trope, where the number of alternate universes is capped at 52. Someone at DC is obviously obsessed with playing cards.

DC has been sweating the symbolism of the number 52 since they couldn’t come up with a name for their weekly series after Infinite Crisis. While deciding that there will be a finite amount of alternate worlds seems random, it isn’t entirely unheard of. Planetary, Warren Ellis, John Cassaday and Laura Martin’s book about superhero archaeologists in the Wildstorm Universe, said that the multiverse was a snowflake that existed in 196,883 dimensions and that theory was based on (possibly junk) popular math at the time.

It’s also really hard to complain when a finite multiverse leads to stuff like this. Multiversity is one of the most compelling arguments for the existence of shared universes out there because of the absolute insanity that it encourages. Limits to the universe allow for symmetry in storytelling and for more structured symbolism, and in this case is pretty much soft toss for Grant Morrison.

5. Goddamn Time Travel

|

| Marvel |

The Crisis on Infinite Earths collapsed DC’s whole multiverse down to one Earth, and distilled 50 years of contradictory comics into one timeline. Shockingly, the condensation of a half century of stories into one set of stories led to some…issues…and the absence of a multiverse handcuffed the storytellers trying to figure it out. Reconciling the numerous different visions of characters that had been continuously published over the company’s history after closing the door on past continuity was complicated – zany ’50s Batman and hairy-chested ’70s sex god Batman were almost diametric opposites. Although, now that I think about it, ’50s Batman did wear a lot of animal prints…

In a lot of instances, DC approach to new continuity was “Screw it, we’ll figure it out later, you guys do what you want.” This lack of direction for their characters led to problems with characterization and plot details. So, to try and clear up any confusion leftover from the Crisis, DC had another giant crossover less than 10 years after the last one, using a freshly-insane Hal Jordan to rewrite the history of the universe from the beginning of time. That’s right: time travel.

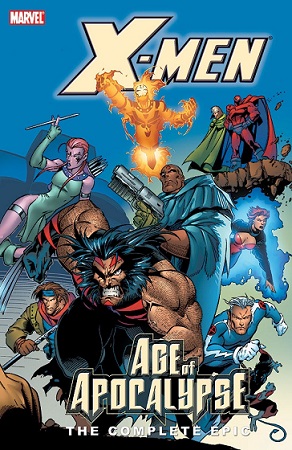

Time travel has worked in genre fiction exactly three times: Looper; the last episode of TNG; and the Age of Apocalypse. Looper because it was about a paradox, “All Good Things” because it had weepy Picard in a paradox, and the Age of Apocalypse because it was about a dark as hell paradox. Please note: all of these stories succeeded because they were about problems that arose from the act of time travel. None of these stories were trying to use Hal Jordan squeezing the baby universe to clear up why Donna Troy had a kid with Disco Stu.

4. Hypertime

|

| DC Comics |

No, not the clock that changes color when you blow on it. Rather this was how DC tried to keep fixing the continuity problems left (“Ha ha ‘left.'” – Hawkman) after Salt and Pepper Lantern gave 60 years of DC continuity a hug. In an effort to get around that, Hypertime was introduced. Basically, it was a many worlds theory that used time travel to work around the “only one Earth” rule – everything happened, but divergences created an alternate timeline instead of an alternate Earth, and some things happened concurrently and were merged together by big events.

Hypertime was Schrodinger’s Continuity. Schrodinger’s Cat, a thought experiment from quantum mechanics, says imagine a cat in a box that is attached to a button that has a 50/50 chance of flooding the box with poison gas if pushed. After you push it, you don’t know whether the cat is alive or dead until you open the box and look. Quantum theory says that the cat exists in both states – alive and dead – until the box is opened. Hypertime says that at the moment you push the button, two distinct timelines emerge: one (call it the You-Dodged-Abuse-Charges timeline) where the cat is alive, and one (Earth You’re-A-Pet-Murdering-Monster) where the cat is dead. The latter also happens to be the Earth that Man of Steel was set on.

The language runs together because they’re more or less the same thing with different names. Outside of comics, this is one of the most commonly used tropes – it’s been in everything from Star Trek to the Zelda games to story mode from Mortal Kombat 9. Even in the DCU, it’s still sort of used – the Beyond comics are considered the canonical future of the DCU, but there’s all sorts of mucking with time going on in “Future’s End” right now. As a tool, though, it was not broadly successful, and has been passionately disavowed by current DC bosses more than once.

3. Retcons

|

| Marvel |

The laziest and usually most hilarious tool for solving continuity problems is the retcon. You see half-assery like this everywhere from Sherlock Holmes’ “I wasn’t dead! I tricked you!” to Professor X’s telepathic macks on Jean Grey to Kyle Rayner’s CIA agent dad to what should be a mandatory postscript for every Nick Fury story, “LOLJKLMD.”

Retcons are new stories that retroactively change something about a character’s history. Sometimes they work: somehow, against all odds, Hal Jordan’s return from the dead not only makes sense, but is a perfectly reasonable and satisfying comic story. The same goes for Bucky/the Winter Soldier: that was one of the best Captain America stories ever. But for every story where you find out about the twin Professor X strangled in the womb that’s now back and controlling the Shi’ar Empire and trying to kill him, you get “oh hey turns out Darth Vader built C-3PO.” FYI, the X-Men one was the good one in that comparison.

Every revelation that Animal Man is the animal equivalent of Swamp Thing in the hierarchy of life on Earth…sees two like Xorn’s brother Xorn pretending to be Magneto posing as Xorn, or finding out that Gwen Stacy had a weak spot for old guys with finger waves, or turning the JLA Watchtower into an episode of SVU, or Superboy punching the walls of reality so hard that Jason Todd came back to life. The bad reeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeally outweighs the good here, in the same sense that Jupiter outweighs Mercury.

2. Marvel Time

|

| Marvel |

Marvel Time is technically a “retcon,” but it’s not precisely that. Marvel Time says that Fantastic Four #1 was published between 10 and 15 years ago today, no matter what day “today” is. It’s a hard rule with ambiguous enforcement. It leaves enough wiggle room to allow some continuity quibbles to sneak by, if you also operate with a sort of “try not to think too hard about it, it’s fine” mantra.

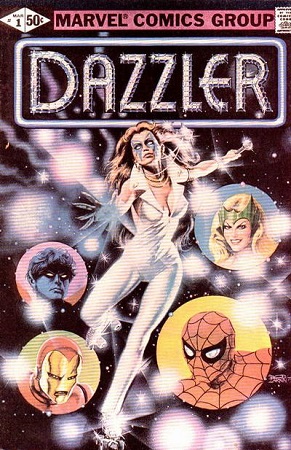

The only real problems it faces are characters who are tied existentially to specific events – Captain America and Magneto and their respective related characters are tied definitionally to World War 2. The Punisher served in Vietnam. Warpath loves mediocre grunge. So unless Dazzler was magically part of the big underground disco scene in the early aughts, making her a contemporary of mid-stage Daft Punk and Jamiroquai and you know what? Nevermind, Marvel Time is perfect.

1. To Hell With It, EVERYTHING COUNTS!

|

| IDW Publishing |

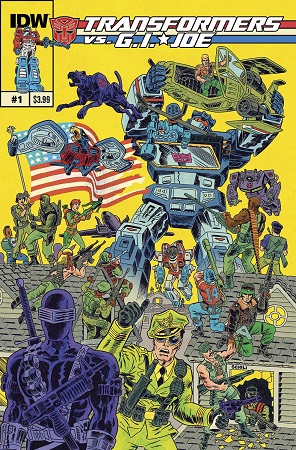

IDW is the 34th company to hold the license to publish Transformers and GI Joe comics. Their approach to continuity seems to be “it all happened, and here are books that follow up on your favorite stories!” For obsessive compulsives trying to hammer everything into a unified timeline, this is muy bad. For people who love the old Marvel G1 comics and want more from the same people, this is great. For people who like Axe-Copish crossovers of the two, this is excellent.

This is also the approach that Rob Liefeld is taking in farming out his Extreme books. There’s no doubt that the person who takes over Youngblood next isn’t going to spend years writing the creation of the Earth Empire to line up with Brandon Graham’s (AMAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAZING) Prophet story. He’s letting his writers write, letting them tell the stories they want to tell first and worrying where it all lines up later. Marvel and DC have occasionally made nods towards this, but there’s always been some editorial necessity that precludes them from going all the way with it, and while the shared universe has certainly led to some amazing stories, the best comics, company or creator-owned, are the ones that only have to care about their internal continuity.