EXCLUSIVE: A Chaotic Conversation With Terry Gilliam

|

Terry Gilliam is a man often surrounded by chaos, from the zaniness of the other Monty Pythons he made a name for himself with, to the battle for control of Brazil and the string of bad luck that derailed his The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. So it shouldn’t have come as a surprise when my interview with him ended up containing some odd mishaps, as my phone call crossed with another call and his publicist lost track of which interviewer was on the line.

In a normal interview, I’d tend to edit such glitches out of the final transcript, but this was no normal interview – Gilliam embraced the chaos of the moment, acknowledging the confusion and riffing on it to a point where our conversation would probably read very strangely without it. Ostensibly, we’re talking about his latest film The Zero Theorem, with Christoph Waltz playing an ex-office drone working out of his home trying to make the universe’s ultimate equation even out. Speaking as one who also works at home and rarely steps outside except for errands, I can report that in a metaphorical sense, the director absolutely nails the weirdness of fully interacting with the world while staying shut away from it at the same time.

We begin right after another interviewer has hung up from a conference line…

Publicist: This one’s going to be 15 minutes as well.

Terry Gilliam: Oh, good.

Luke Y. Thompson: I’m on the line. Hey, Terry! How are you doing today?

TG: He’s late! He’s here. I was just going to say, that’s it. If he’s not here on time, we’re off. But no, he’s here. [chuckling]

LYT: Absolutely. It’s a real pleasure. When I was younger, I had the published screenplay for Time Bandits, and in the pre-VCR world, me and my dad would always act out all of the parts.

TG: [laughing]Did you squat while you did the Time Bandits from the film?

LYT: No, we would do it sitting down. But we should have. We should have gone more Method.

TG: On your knees.

LYT: I look back and I think of how many screenwriting in-jokes were in that that I didn’t know at the time. I mean, I knew “PULL BACK TO REVEAL NO TROUSERS” was obviously one. It struck me that you probably have trouble doing that now, putting out something with these in-jokes that at the time weren’t just commonly known. You’d have people saying you have to dumb it down so that everybody could understand it.

TG: Well, I’m luckily not having to do that. I just do what I do. [chuckling]And get the smaller budgets to do it with.

LYT: Speaking as someone who works at home, I think this movie really nails what it’s like in a spiritual sense.

TG: Good, good. I think there’s a lot of people that do work at home, and know and understand that. Those that work in corporations don’t get the movie at all.

LYT: Is there part of your work that’s analogous to it? You think of a director as working with a lot of people, but does this represent what it feels like in the post-production process, for example?

TG: No, it’s more about – I suppose it’s – because I’ve got a big 32-inch, hi-def computer screen, and I just find myself completely hooked on it. I’m a victim of both the actual physical technology, and the web, because there’s all this stuff there to focus on, rather than go outside and romp in the grass. So I become – I can find myself for days just sort of disappearing, and I’m still sitting in front of my screen. So I can identify with [Waltz’s character] Qohen that way.

And also, Qohen, I identify with because I was really pushing the idea of try to be alone to find out who you are. That’s my goal in life, to encourage one and all to understand solitude.

|

LYT: There’s something of a vampire to him, as well. I was just watching the Herzog Nosferatu, and there’s something of the lonely eternal about him, as well as the scene where Qohen kisses her finger, which is sort of the classic Dracula moment, where Dracula sucks on Harker’s blood for the first time.

TG: [chuckling]You know, you’re right. Nosferatu, Herzog’s version, [Klaus] Kinski is just wonderful. He nails the loneliness of the guy who can’t die. And that’s the part of vampirism that I find interesting. I’m actually bored of vampires, because I can’t get away. Vampires and zombies and Marvel’s superheroes are crushing me at the moment. There’s no escape from them, unless you sit at home alone and cut yourself off.

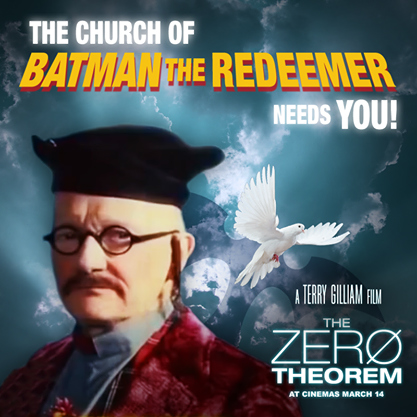

LYT: Well, speaking of superheroes, it’s interesting that you have the reference to the Church of Batman in there. Was that something that had to be cleared with DC, or is that just sort of stuck in there?

TG: No, no. I just – I mean, no, we didn’t do the Batman symbol. That’s the point of that, just so we didn’t have to get in trouble. But they don’t own the word ‘batman,’ because the batman used to be a 19th-century England military assistant. So fuck ’em! [laughs]

|

Publicist: Now that’s a perfect way to wrap up! So thank you, Matthew.

LYT: Wait, I’ve only had five minutes.

TG: No, we’re on to Luke, actually.

Publicist: Oh, I’m so sorry.

TG: That was a very short one. I think we ought to give it another few minutes. That’s too short.

P: Of course, I think I did the…

TG: Thank you for coming in and trying to save me, but I think we should run a little bit longer.

P: [laughing]I’ll come back in about six minutes.

TG: Whatever, yeah, OK.

LYT: So originally Billy Bob Thornton was going to be in this role, and I can only imagine this would have been very different. Not only because of the accent, but because his rhythm of acting is so different.

TG: Yeah, that was about six or seven years ago, when the project first came up, but Billy Bob had problems traveling then, and it never came together, so when it resurrected itself this time around, Christoph just seemed to be the guy to do it. I had met him previously at some awards ceremony, and we were both keen to work together. I just thought he’s got the chops to do it. I think Billy Bob is great, no question about it – he’s brilliant. But Christoph, in the world of movie making, was more bankable.

LYT: Interesting. Did you have to retool it very much for Christoph, or was it in the embryonic stage?

TG: No, not, not at all. We didn’t do anything differently. It was the same script. And they both – Billy, in the Coen brother’s film, The Man Who Wasn’t There, I just thought he was so brilliant, his character floating through it. But Christoph has his own bag of skills, and he really understood the character. Plus, I think it’s the best thing he’s done, because he’s never off-screen, with no place to hide. It’s a very hard part to pull off.

LYT: There are – I’m sure everyone brings this up – the most obvious parallel is to Brazil of all your other movies. It’s sort of like the you had the blatant dystopia of soul crushing work at the time, but now you have thatwith a happy face, like Google, “Don’t be evil.”

TG: Exactly! Everything is nice now. The world is colorful, and fun, and we work in a playground, basically. I think it’s my first utopian film. There’s only one guy who’s a misery guy who just can’t seem to get on the rhythm of the rest of the world, so we have to sit and watch him for two hours.

LYT: Is it more fun in a movie like this where you’re building a world from the ground up? You haven’t really done that in a while. A lot of your more recent ones have been set in the real world. When you get to play and create a whole reality from nothing, is that harder because it’s more production design, or is it more fun, because it’s freeing?

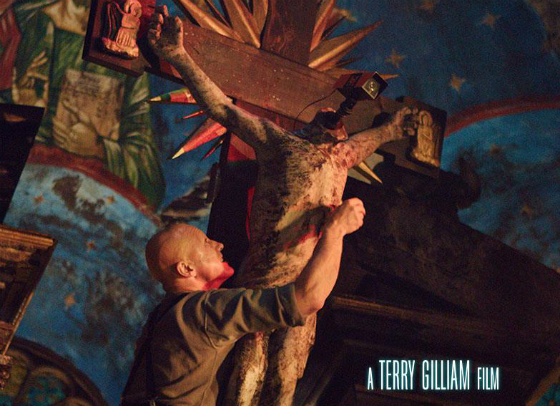

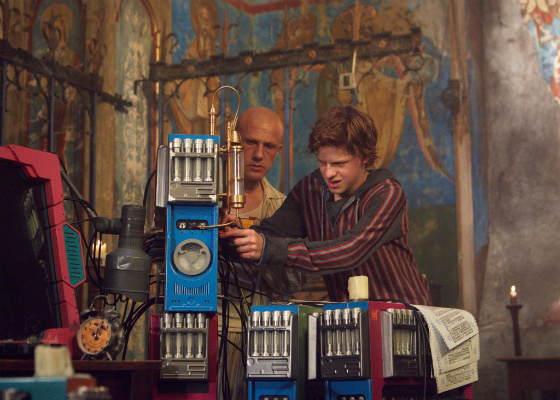

TG: No, it’s easier for me, because the contemporary film is really hard, because you’ve got to be accurate, and I can’t decide. “A t-shirt like that, or not?” When you do this, it’s like me being basically a political cartoonist, almost, because the world is a satire of our world at the moment. So you build all of that. I love it. I can add this thing – at each point, you’re adding things to it, and you’ve got the opportunity of ladling a lot of symbolism inside that church.

A call behind the altar is John the Baptist, baptizing Jesus, and there is the Holy Spirit in the form of a white dove descending, and that’s the call. And then you have a few of them living in the church as well, some real doves. And you just play with that all through it, and I love being able to create my own world, which is just an abstraction of the world that I think we’re living in right now.

|

LYT: You’ve been satirizing marketing and commercialism ever since the Python days, and through movies like Time Bandits. Does marketing and commercialism ever get so absurd that you think “I can’t possibly satirize this,” because it’s gotten so ridiculous?

TG: I guess not! [laughs]I don’t think so. It’s just endless. I just love taking, like, Occupy Wall Street, and turning it into Occupy Mall Street. Shoppers of the World Unite! You take political slogans that have some substance to them and you turn them into dross, to sell whatever they’re selling.

I find it’s playful, and sometimes it’s almost prescient, because I had him saying “The future has come and gone. Where were you?” And in the course of making the film, I thought I was creating a slightly not-too-far-in-the-future world, and it was already historical by the time we finished the film. The world we’re living in is just moving so fast. I don’t think anybody is in control. Nobody really knows. Everybody is just doing their own separate thing. It’s going to lead to what – I don’t know yet, but I can’t wait to find out.

LYT: It’s interesting that so many of your movies are about people escaping from the real world into their own imagination, and this one actually brings it full circle with we actual have virtual reality now, and people do that. Do you feel like you predicted that, and is that still sort of the best escape from the numbing cultural effect?

TG: I don’t know. I still think imagination is still absolutely necessary. I think the sad thing about Qohen, he doesn’t really have much of an imagination. Of all of the characters that I’ve had as the main one, he’s not an imaginative person. He doesn’t think. He doesn’t even consider what the Zero Theorem means. It’s just a job he’s good at. He works. He’s a drone, in that sense.

[SPOILERS in the next paragraph]

In the end, the world he ends up in is a virtual world, but at least he seems to have found a kind of calmness, a dignity within that world. And that’s very sad, that’s my problem. To me, it’s the saddest movie film I’ve done, because I think too many people are like that. They find comfort in the virtual world. The real world and real relationships are too complex, too messy. So we’re offered these worlds. You can sit there on the web, and not have to deal with real people. So it’s mainly a movie for all of them – those people.

[End spoilers]

LYT: Do you feel like religion sort of offers that kind of virtual world as well? It seems like the whole waiting for the phone call sort of sums that up, either as an addiction or as an escape.

TG: Well, that’s exactly right, and that’s what addiction can be. Maybe religion has more, in some cases, profundity, than a virtual world. But who knows? I don’t know. People use religion as a refuge. That’s what it’s there for. It’s also a way of not having to think anymore, not having to deal with things. Or if things go wrong, you now have an explanation for them. It’s simplifying things, I suppose. I just keep trying to encourage people to not accept somebody else’s version of what the world is.

|

LYT: There’s a great line where Bob says, “Old people do the same thing day after day.” How have you managed to avoid doing that?

TG: [laughs]I haven’t! That’s the problem. That’s the important line. I work hard at not getting good at doing what I do. As long as I keep failing enough, life will have to keep being interesting to survive. Now, I feel that I do end up doing the same thing every day, again and again, as I get older. It’s quite frightening. I’ll go to make the coffee in the same way, almost at the same time. How I have the same breakfast, how I sit on my computer and do the same bullshit stuff, day after day, and it’s reaching the point that I’m getting bored with it as well, just like Bob.

LYT: Do you feel like the whole theme of trying to defy chaos, is that equivalent to mounting a production sometimes?

TG: Yeah! [laughs]Yeah. I mean, for a brief moment, you take chaos, and you bring some order to it. And out of it comes something – a film. And then it’s back to chaos again. It always feels that way. But the idea of order winning is probably much more boring than chaos winning.

LYT: As an old-school animator, what’s it like for you working with CG in this one?

TG: It’s the same, except I’m not doing it myself. I’ve got to talk to other people and discuss and describe and say “I think it should look this way, it should be like that.” But then at the same time, it’s like the rest of the film making process. It’s collaborative, and so people are coming up with different versions of the thing, and some of them are much better than my version, and those are the ones that will stay. There are times where it’s frustrating that I don’t have at my fingertips the skills needed to do it exactly the way I want it, but that’s just the way that film making is. And I’m not ready yet to go back to doing cut-out animation in my life.

LYT: I’ve heard also that you’ve been talking to Laika about doing an animated film. Is that still in the pipeline?

TG: I keep hearing about this as well. We keep meaning to have a phone call discussion, and we never quite get it together.

LYT: That would seem like a dream project – the whole hand-made nature of what they do seems sort of tailor made.

TG: Oh, they’re very good. It’s such a long process. I don’t know whether I can be as useful, because I wouldn’t be there all the time. I’d just be floating in every so often to suggest or criticize or change. And that’s not quite as satisfying as when I’m making a film. Every day I’m there in the heart of the whole thing, making the choices and decisions, and arguing with everybody. It’s that kind of complete focus of the work that I’m best at, and I’m not sure how to be as gifted as Tim Burton is on most of his animated films – let’s put it that way.

LYT: One of the great things about your old cut-out animation was that there was – it didn’t look slick and perfect, there was an awkwardness to it that was part of its charm. With CG, everything looks so polished. Is it harder to get that personal style on something like that?

TG: Yeah, I think that really is a problem. CG always ends up being so tiny when I use it in my films. I do my best to try to fuck it up whenever I can. The old cut-out animation – it was the crudeness of it that made a lot of it work very nicely, and how do you do that with computers? It’s in things like South Park – now South Park is all done on computers, but the computer is putting the shadows around what is supposed to be cut-out animation.

LYT: Exactly.

TG: It’s not quite the same as what you do in your film. It’s mannered, I would say. So I never got into it too deeply. And the Laika phone call is still waiting to happen.

LYT: What was it like revisiting the old animated stuff for the Monty Python reunion? Was it still cut-outs or did you enhance it?

TG: No, I didn’t have to do anything. We just cleaned it up – refreshed a few bits and pieces. I was very pleased with the reaction, when I read reviews of the show – they all were really surprised with how alive and vibrant and refreshing the animation is. That’s great to hear, because it is what it is, and it’s nice that it feels fresh to people. I don’t know – my mind doesn’t quite think that way anymore. I have to really convert to a different Terry Gilliam to think the way I did when I was doing that animation.

LYT: On that note, the most pseudo-profound question I can muster: Between this movie about the meaning of life, and the previous movie called The Meaning of Life, has your impression of what the meaning of life is changed?

TG: No. [chuckles]There is no meaning to life. Life just replicates itself and goes on and on and on. Everybody’s got to do the work, they’ve got to create the meaning, and I still haven’t worked it out, personally. I can’t speak for others.

Publicist: Thank you, Matthew. That was a good one.

LYT: This is Luke, not Matthew.

P: Oh, this is Luke. Good news.

TG: We just need Mark and John!

P: Oh, then you have a few more minutes to go, then.

LYT: I feel like saying “My name is Qohen!”

TG: Now here’s something. This is the biblical names came floating up. I only discovered last week, it was actually on a blog site from Canada, why he is called Qohen Leth. I always asked Pat Rushin why he was called Qohen – with no ‘u’ – Leth. A strange last name. The answer is Ecclesiastes. The book of Ecclesiastes, the Teacher is called, in Hebrew, Qohen Leth. Ba-boom. So Zero Theorem is very much the book of Ecclesiastes for the 21st century.

LYT: Fantastic. That’s awesome.

TG: You thought the other answer was a good one! And I didn’t know that, but that’s what I’ve made – this is reality, how it works.

LYT: That’s God speaking through you somehow.

TG: Well there you go! And the strange thing is I am also doing an autobiography, and I was going to do a little intro in it, and it was going to begin with “Vanity of vanities, all is vanities,” which is Ecclesiastes. These are the weird moments in film making.

LYT: And the fantastic ones. Thank you so much, Terry. It’s been an honor, and I can’t wait to see what you do next.

TG: Thank you. Me too!

—

The Zero Theorem is currently available on demand, and opens in theaters Friday.