TR Interview: Director Dean Israelite on the Found-Footage, Time-Travel Mayhem of Project Almanac

|

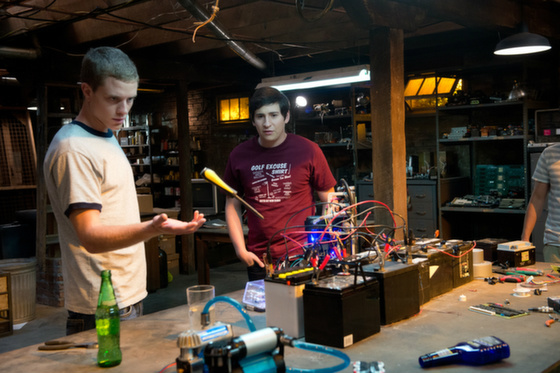

Found-footage is most frequently used as a device to scare the audience, in the hopes that showing them something through the lens of something they own makes it feel more realistic and grounded. Project Almanac takes an even bigger leap with the format than ghosts, however, by showing us footage that has traveled through time – repeatedly (yes, the last Paranormal Activity pulled out a time portal, but only briefly, and as a “surprise” ending).

Believe it or not, this low-budget movie that uses hand-held cameras and actors who look like they could actually be in high school was produced by Michael Bay and directed by Dean Israelite, cousin of the guy who brought us the Ninja Turtles reboot. I’m embargoed from opining at length on the film, but suffice it to say I’m not surprised female lead Sofia Black D’Elia is already headed for bigger things (female lead in a needless Ben Hur remake, but still) – she’s that rare oxymoron of a believable dreamgirl, in a part that would have gone to Shannyn Sossamon 15 years ago, or Teri Hatcher 25 years ago.

But we’re here to talk to the director, and thankfully, he had quite a lot to say.

|

Luke Y. Thompson: So the obvious question: It’s now the year 2015, you have a time travel movie with the word “almanac” in it – how much is Back to the Future II on your mind?

Dean Israelite: What is so interesting – maybe serendipitous, I hope, for us – the movie was meant to come out last year. So maybe it’s just a good omen, I’m hoping? But we have a lot of respect, obviously, for the Back to the Future franchise, and once I got the job on this movie, I don’t actually think I went back – I think I went back and watched the first Back to the Future once, but I didn’t – as I started to do that, I didn’t want to keep rewatching it, because we were trying to enter the genre in our own way. But you can’t have anything but respect and admiration for those movies.

LYT: I know this has gone through a couple of title changes, and I was wondering if there was ever any worry that “almanac” is not a word that the kids today would understand. But then I thought that maybe Back to the Future II is enough, that that’s how they would know it?

DI: I wonder. I wonder if teenagers today have gone back and watched those movies. I don’t know. I’d be interested – I’d be interested to know. For us, it’s a cool title. I’m of the mindset – because there was a lot of discussion about this, obviously, that the title changed at one point, because people were afraid that no one understood what an almanac was. To me, that’s OK if that’s a provocative title, which I think it is.

|

LYT: Was it always, as a script, a found footage film? Was there ever any consideration of doing it otherwise?

DI: Sure. To begin with, my intention wasn’t to make it a found footage movie. It was always going to be a type of a hybrid. So in the script, they always had their own devices and their cameras, and that became a way into some of the scenes, and it became a way to ground the movie and frame the movie in a real way. I, to begin with – my initial concept was to make it feel like something akin to End of Watch, where you’re coming into scenes through the cameras, but then you are cutting to other cameras that aesthetically feel the same, so you don’t, really, feel the cut, but you are getting perspectives that the characters cameras wouldn’t otherwise get.

As we developed the script, it became important to the studio to be able to frame the movie as a complete found footage film. So I had to go back and look at the scenes and storyboard the scenes for myself and figure out – could I achieve the feel I originally wanted with all of the limitations that came with making it a quote-unquote honest found footage movie.

And I felt like not only could I achieve the same feel, but maybe it would push me to make unconventional choices that I wouldn’t otherwise make, and perhaps there is opportunity in it. And that’s really when we all came together and said OK, we’re going to make this a found footage film.

LYT: And do you feel, having done it, that it did force you to make unconventional choices that ended up being really good?

DI: 100%. I mean, I think that there are a lot of scenes where I’ve had to frame it in a weird, wide master shot. I’m not able to move the camera around, and so I had to rely on my blocking skills, and keeping the scene alive with all of the staging of the actors. That pushed me to do things I otherwise wouldn’t have. I just would have moved the camera and put a cut in, and being able to get the close up, and now I had to work with the choreography.

I also think the way that we were able to integrate the camera into the time-travel scenes – the way the camera gets manipulated itself, becomes inventive. There are things I wouldn’t otherwise have done. For example, in the scene where they first test it on the Barbie Corvette, we wanted a wide shot, so we had to put it down on a table. We wanted a dolly shot, so we had to get the characters to move the table. We wanted a jib shot, so we came up with the idea that the camera would levitate with all of the other objects in the room – it pushes you to those places.

LYT: When you have special effects and things levitating and all that, is it harder to composite that when you have to match it to a hand-held camera?

DI: Yes. Definitely. Much harder to do the visual effects – you’re constantly trying to make sure that on set you are being responsible to the scene that you are telling, and creating the energy you want to create through the photography, and at the same time being responsible to the VFX supervisor who’s breathing down your neck, trying to get you to calm things down so that ultimately you can get it done well. It’s always a trade-off.

LYT: Was there ever a moment when, in post-production, you looked at a scene and said “OK, we have to go back and do a re-shoot to get this particular effect, but we improv’d the cinematography at the time, so how are we going to match it up?” Anything like that?

DI: Not really, because almost all of the film is shot-listed. In fact, all of the film is shot-listed. Maybe we didn’t ultimately shoot those shots, because on a day we would have changed stuff, but every shot was conceived of ahead of time, especially the scenes with the visual effects. Those were all story boarded, and so on set we are all on the same page, and we’ve done enough prep work to hopefully not surprise each other. Ultimately, that helps in post-production. Of course things don’t work exactly how you planned in post-production. Then it becomes less about – for us, at least, we’re on a limited budget – it becomes less about re-shooting it, and more about trying to re-conceive the effect in post.

|

LYT: There are things I want to ask that I feel are too spoilery, so I’m going to try to ask them in very broad strokes.

DI: OK.

LYT: What’s the running time of the tape that they find in the camera?

DI: Oh, man. [laughs]I mean, it’s filmed, in my mind – I don’t know if anybody has – I’m sure the writers would have a different answer to all of this. In my mind, it’s filmed over – oh, I understand why that’s a spoiler! [thinks]Well, the camera times out, you know. In my mind, the story really takes place over the span of a couple of weeks, besides for what would then, ultimately, be a spoiler.

LYT: I was sort of wondering – every time you see a found footage movie, you kind of think “Who found this? Who put it together?” Is it in your mind that someone edited this film, or are the edits all the camera timing out?

DI: To me – and again, we obviously bend and break the rules, and I think we’re unapologetic about it, because again the story and the emotion is more important than the feel at the end of the day – they need to work in tandem with each other. To me, it’s conceived as if, I suppose, the tape is “found” – no one has edited this. That’s why there are a bunch of jump cuts, that’s why there are a bunch of glitches in the film.

|

LYT: And your rules of time travel, initially when watching it, it’s as if everything that will happen has already happened, because he sees himself at the birthday party, which is no spoiler, because that’s in the trailer. But then about mid-way through it becomes apparent that that’s not necessarily written in stone, because they can change things. Did you ever sort of write down all the rules and figure out how those two things work together?

DI: Yeah. In our minds, it’s a loop. But it’s a loop that’s happening for the first time. And so if you looked at a movie like Looper, I think we have a lot in common in terms of the rules that we’ve laid out. You either buy into that logic in Looper, or none of it makes sense at all, because in Looper, it wouldn’t have – he kills himself at the end so how did he exist even at the beginning when it started watching him. The only way in my mind that that makes sense is that we’re watching the first time that loop happens.

LYT: Exactly. I actually know Rian [Johnson] and he told me that.

DI: Great! Good. OK. Then we’re in synch. [chuckling]

|

LYT: How much were you thinking of time travel as sort of a drug addiction metaphor in this film? It feels like it turns into that a bit towards the end?

DI: Yeah, a lot. We used that vocabulary. I spoke to Johnny about that sort of thing, about the obsession that came with that. And we often, even in the writer’s room, were talking about this guy having to hit the crack pipe over and over again – where does that lead you?

LYT: We mentioned Back to the Future as a possible influence, but I also want to ask you about maybe Butterfly Effect, or the classic short story “Sound of Thunder,” which it sort of reminded me a lot of The Simpsons episode of “Sound of Thunder,” where Homer keeps going back to try to change things, and eventually, he’s like “Eh, close enough,” because he gets the universe almost the same way, but then they have frog tongues.

DI: Right, right. You know, I get asked this question a lot, and the truth is, I’m sure the writers would have a more interesting answer in terms of what their influences were, because they lived with this for so long before they – before I even saw the script. I came to it from their script. I loved what was in the script, and to me that was the guiding principle. It wasn’t as if I’d been inspired by a lot of time travel movies and so wanted to make a time travel movie. I just got their script and wanted to tell that story.

LYT: For the Lollapalooza sequence, there’s a lot to ask about this. First of all, was it written in the script as Lollapalooza specifically?

DI: To begin with, it wasn’t. It was written as a music festival, and we actually, through production, went down the list of where can we do this? It started as Coachella, and then we were in Atlanta, and so we were like “Maybe we can go to Bonnaroo?” We went down – there were one or two others, I think. No one would have us, except Lollapalooza. And it turned out to be a fantastic centerpiece for the movie, because you’re not just at a music festival – you’re in Chicago, and you have that skyline, so it’s so cinematic. They were kind enough to let us go do it there.

|

LYT: So when we see and hear Imagine Dragons on the stage, are they actually performing that part of the song at that point in time, or did they shoot extra coverage for you? Because I noticed they’re listed in the credits almost as if they’re actors.

DI: It’s live. We shot that as they were performing it. We didn’t get a second chance. We were really guests at their performance, and they were kind enough – we had a meeting before, and they were kind enough to let us shoot their performance, but there was no extra coverage. There was no filmmaking beyond almost documentary film making involved in that.

LYT: So then is all the dialogue ADR from the main characters?

DI: In the crowd?

LYT: Yes.

DI: During Imagine Dragons, or all of Lollapalooza?

LYT: During all of Lollapalooza. It must be hard to isolate, because you’ve have music in the background that wouldn’t be matching.

DI: Yeah, it’s a combination. Some of it is – we did have mics on them – some of it is production sound, and if you listen closely you’ll probably hear music in the background that we’re trying to kill in the silences between their lines, and some of it is the lines that you just couldn’t hear and we couldn’t dig out, we ADR’d.

|

LYT: Was that sequence the biggest technical challenge in making this, or was there something even bigger? What was the hardest thing?

DI: The hardest, technically, were the time travel sequences. Like the one I mentioned before with the Barbie Corvette, because there you have to craft a scene that feels theatrical, that is telling the beats of the story between the characters, and is advancing a love story in some ways, so it needs to feel intimate, and you have to do all of that through the framework of found footage. And everything has to work in synch – the choreography with the props, with the practical effects that are going on in the scene, with then realizing what the visual effects are going to do on top of that.

Those were the most difficult to conceive and then execute. Lollapalooza was not hard to execute from that standpoint. It was only hard because it was labor intensive. You’re running around for 14 hours at a music festival that spans miles, and trying to get scenes that you’ve written, and improvise scenes that you feel are going to be good on the fly. That’s what made that challenging.

LYT: It feels like lately there’s almost a posse of South African sci-fi directors in Hollywood, with Ender’s Game and District 9 and Ninja Turtles. Do you guys get together like a clique ever? Did you guys sort of grow up with the same media? Was sci-fi a big thing at the time you were all young?

DI: Man, I don’t know. Gavin Hood, who did Ender’s Game, obviously, is of a bit of a different generation, so I’m not sure what that is. I’m not sure what that is. A lot of it has to do with the industry itself, right? There are just a lot of high-concept movies out there in Hollywood trying to get made, so that’s a lot of what is out there, in terms of what you’re going to choose from.

LYT: So are you particularly drawn to sci-fi then, or is it just that this was available?

DI: I don’t want to be disingenuous. It’s not that – I loved this script from the start, so it’s not that something like this was just “available.” I loved the script from the start. It’s not that I saw myself as a sci-fi director before this – I was just drawn to the story, drawn to the coming-of-age story at the center of it, and then thought that the time travel element could be done in an inventive way if we found our own grounded, real way into it. And that’s really what excited me – beyond thinking about whether I am or am not a sci-fi director. It was about the story, and how I could push the boundaries of the story telling.

—

Project Almanac opens January 30th.