Ten Amazingly Strange Celebrity Hotlines of the 1980s

|

Before we had the Internet, we had celebrity hotlines.

I don’t like making phone calls, and I never have. But back in the 1980s, we were constantly being exhorted to pick up our telephones and call, call, call! It was often a celebrity telling us to do it – and really, who can you trust if not a famous person, even if we have to pay? Here are ten particularly noteworthy (and occasionally tragic) uses of premium-rate telephony during the Reagan years.

1. The Empire Hotline (early 1980)

800-5-21-1980

Charges: Free!

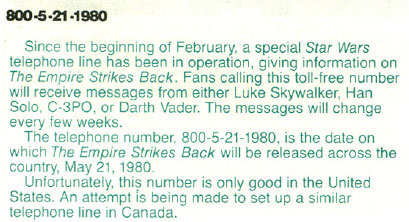

In the Winter 1980 issue of Bantha Tracks, the Official Star Wars Fan Club newsletter, the following appeared:

|

Premium-rate calling was in its relative infancy at the time, and the number was intended to be a promotional tool for The Empire Strikes Back rather than a source of profit, so it made sense for it to be a toll-free call. (Lucasfilm was extraordinarily nervous that the public would lose interest in Star Wars before Empire came out, the most extreme example of that anxiety being The Star Wars Holiday Special.) As Lucasfilm’s then-Director of Fan Relations explained to StarWars.com some thirty years later, the needed “521” prefix was only available in Illinois, and the influx of calls to the not-yet-computerized system basically broke AT&T for several hours.

The messages themselves are what we would now consider to be very spoiler-y. Harrison Ford sounds like he’d rather be anywhere else doing anything else, and Carrie Fisher slurs the word “scourge” so much, it sounds like she’s about to slide out of the recording booth. And all of them demonstrate why it’s a bad idea to try to shoehorn the words “the empire strikes back” (or anything else written by George Lucas) into a sentence spoken aloud by human beings.

2. Saturday Night Live: Kill Larry / Dump Andy (1982, 1983)

Save Larry: 900-720-1808

Kill Larry: 900-720-1909

Keep Andy: 900-720-4101

Dump Andy: 900-720-4202

Charges: $.50 per call, because that’s just the way the phone company works.

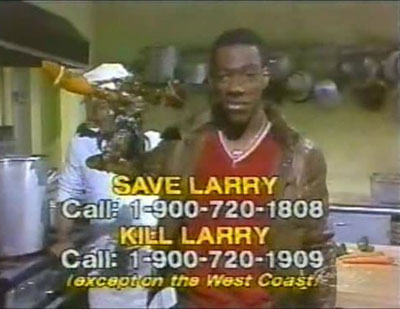

|

On the April 10, 1982 episode of Saturday Night Live, Eddie Murphy put the fate of a lobster named Larry to a vote. Viewers on the East Coast could either call one number to save Larry the Lobster, or call the other number to kill him. (Then as now, viewers on the West Coast could go straight to hell.) Much like with the Empire Hotline two years prior, AT&T was unprepared for the onslaught, though the system managed to keep afloat in spite of the hundreds of thousands of calls. By the end of the show, the tally was in: 239,096 to save him from being boiled alive that night, 227,452 to let him fulfill his delicious, bib-splattering destiny.

The stunt was not without controversy. The following week, Murphy read an angry letter from a University of Oklahoma student who managed to be humorless, self-righteous, and racist at the same time. Murphy then proceeded to eat Larry (or a Larry lookalike, as the case may be).

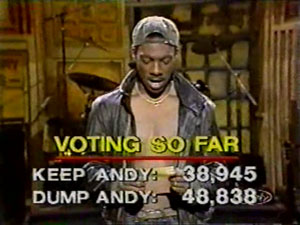

On November 20, 1983, a similar call-in vote was held to determine whether or not Andy Kaufman would ever appear on Saturday Night Live again. His confrontational, life-as-performance-art shenanigans had begun to wear thin with much of the public, especially his recent wrestling matches with women and attendant misogynistic rants. (Whether they were an act or not, very few people found it funny, which was of course the point.) According to Bill Zehme’s Lost in the Funhouse: The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman, the poll had been Andy’s idea, and he was confident that he would win.

Except that when Eddie Murphy appeared a little later with the results so far, things were not looking well for Andy, at 38,945 to Keep and 48,838 to Dump.

|

Mary Gross handled the next update: 105,316 to Keep Andy, and 134,691 to Dump him. “Uh-oh, time to boil the water.”

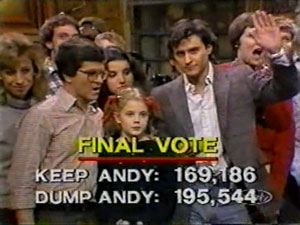

By the end of the show, the results were in: 169,186 to Keep Andy, and 195,544 to Dump. (And, yes, that’s a young Julia Louis-Dreyfus standing behind an even younger Drew Barrymore.)

|

It’s worth noting that while 466,548 people called in with an opinion about a lobster, only 364,730 called in regarding Andy Kaufman, and the majority of them were calling for the express purpose of kicking his career in the teeth. Oh, democracy! When it works, it sometimes tells us unpleasant things about ourselves – a lesson which DC Comics would learn the hard way some years later.

3. He-Man (mid 1980s)

900-909-2233

Charges: $2.35 for a two-minute message. $2 for the first minute, $.35 for each additional minute.

Though the Golden Age wouldn’t kick in for a few more years, this is in many ways the archetypal 900 commercial. It’s poorly dubbed to mostly unrelated footage, and vague about what one might actually hear were they gullible enough to call. Among the things promised are a) journeying to distant worlds, b) exploring the universe, and c) potential Skeletor battles, the latter mostly to sate Orko’s apparent bloodlust. He-Man also promises that “we’ll also tell you how to get an action figure” (on-screen disclaimer: “Action figures may vary from figures shown”), because if there was anything the He-Man series was lacking, it was advertising for the action figures.

And just to show that they weren’t entirely money-grubbing weasels, a subtitle makes the unverifiable claim assures us that “A portion of each call goes to the Calif. Museum Foundation & Local Science Museums,” though She-Ra clarifies aloud that only part of that first two minutes goes to local science museums. How much is a part and/or a portion? A dime? A penny? A mill? And if you stick around after the initial “message,” that $.35 a minute goes straight to the weasels.

4. Captain Lou Albano Wrestling Hotline (1987)

900-960-4LOU

Charges: $1.50 for the first minute, $.35 for each additional minute.

In addition to being shockingly inexpensive for the time, this is a peculiar example in other ways. The celebrity is actually on camera, and while he makes a vague promise of “talking about the world of pro-wrestling,” if you called at certain days and times prior to August 31, 1987, you could be “randomly selected to be eligible to have a live conversation with Captain Lou.” The thing is, I knew kids who would have been thrilled at the prospect of being randomly selected to be eligible to have Captain Lou yell at them over the phone. Also, whoever wrote the copy has a good sense of humor: “Call the Captain Lou Albano Wrestling Hotline! Available until further notice…or a hearing.” By the standards of celebrity hotline voiceovers, that’s pretty clever.

5. The KISS Hotline (1988)

900-909-KISS

Charges: $2 the first minute, $.45 each additional minute.

KISS has never shied away from television; at their peak in the 1970s, they did more commercials than most bands for both their albums and their merchandise. So it made perfect sense that around Christmas of 1988, while in the dregs of their post-makeup, heavy-metal career doldrums, they did a 900 number to promote their compilation album Smashes, Thrashes & Hits. Gene Simmons sounds like he cares exactly as much as he ever did about anything, but Paul Stanley is more game, describing calling the hotline as “Your front-row ticket to KISS – it’s like being at the show!” Yikes – no wonder they had such trouble selling tickets.

6. The Rap Hotline (ca. 1988-90)

900-909-JEFF

Charges: $2 the first minute, $.35 each additional minute.

Career-wise, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince were having a much better go of it in 1988 than KISS, but that was no reason for them not to have a 900 number as well. It wasn’t promoting any album in particular, but rather just offering up “the inside scoop on the hip-hop scene,” back in the days when Jaden and Willow’s future papa might actually know what was going on in said scene. The footage is taken from the “Parents Just Don’t Understand” video, but you have to give Will ‘n Jeff credit for going to the trouble to actual performing a jingle, even if it’s thirty seconds long and probably took twice as long to write. But what did you expect – a rewrite of their best song, “A Nightmare on My Street?” And speaking of such things…

7. Freddy Krueger Hotline (ca. 1988)

900-909-FRED

Charges: $2 the first minute, $.45 each additional minute.

I have vague memories of seeing this commercial running during the Freddy’s Nightmare anthology series. As usual, what you might actually hear should you call is left vague: “I’ve got some tales to tell! Freddy’s favorite bedtime stories … [self-satisfied laugh] … deadtime stories.” Yeah, we see what you did there, Freddy.

8. Dial M for Monsters (1989)

900-89-MAURICE

Charges: $.95 per minute. The cost of the call should be $.95 to $4.75.

Speaking of both horror and hip-hop, this doozy combines the worst of both, in that the very bad Beetlejuice ripoff Little Monsters is being promoted with a very bad fake rap song, specifically a Beastie Boys clone. (The Beastie Boys are by no means fake rap, but this song very much is. Hey, did you know that Jake Fogelnest has traced fake rap back to that one Fruity Pebbles commercial?) Well, it wasn’t promoting the movie, exactly, since this actually appeared at the beginning of the VHS release, and to the best of my knowledge, it wasn’t actually shown on television – and thank goodness, because it drags on for the longest two minutes of your life.

It’s essentially a sweepstakes, cross-promoted with the video store displays as well as the venerable teen rags Super Teen, Teen Machine, and Loudmouth (say what now?). The Grand Prize was a trip to Hawaii, which is okay, but not nearly as cool as the First Prize: a Black Knight 2000 pinball machine. Granted, to the target audience of Little Monsters in 1989, a pinball machine probably seemed impossibly old-fashioned, but it looks pretty great now.

9. Mojo Nixon & Skid Roper, “(619) 239-KING” (1989)

619-239-KING

Charges: Free! (Standard long-distance rates apply.)

My personal favorite, since I actually called it. For want of a better description, Mojo Nixon is a pscyhobilly comedy-rocker who’s best known for the song “Elvis is Everywhere.” But his Elvis fixation didn’t end there, and 619-239-KING was a real phone number which he implored Elvis to call, and/or for fans who’ve seen Elvis to call Mojo and tell him all about it.

Mojo didn’t actually believe that Elvis was still alive, of course. In this TV news segment from the time, Mojo explains how he’s doing it for what we would now call the lulz. He also plays some of the goofier calls he’s received (not my call, phew!), including some very bad Elvis impressions:

Lest you doubt my connection this great moment in pop culture, history, here’s my “(619) 239-KING” cassingle in front this very website.

|

Congratulations. You are now jealous of me.

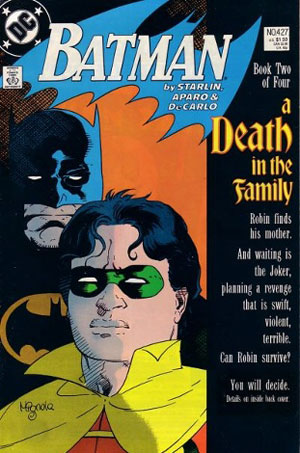

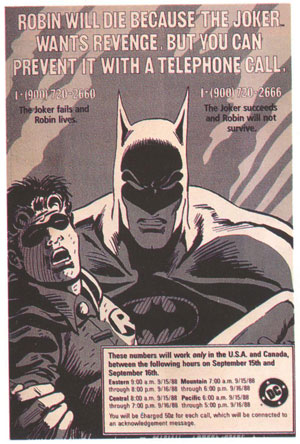

10. Batman: “A Death in the Family” (1988)

The Joker fails and Robin lives: 900-720-2660

The Joker fails and Robin will not survive: 900-720-2666

Charges: $.50 for each call, which will be connected to an acknowledgment message.

|

If the Saturday Night Live polls taught us anything, it’s that crowdsourcing is a lousy way to decide who lives and who dies. (The rabble has been getting it wrong since Barabbas, all things considered.) It’s a lesson that was roundly ignored by the DC Comics editor Denny O’Neill in 1989, who suggested using the so-very-popular 900 numbers as a means of dealing with Jason Todd, the increasingly unpopular Robin.

DC could, like, change the character, let him grow and evolve as a person, or they could have the Joker blow him up and let the public decide his fate. They went with the latter option, and in Les Daniels’ book DC Comics: A Celebration of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes, O’Neill makes no bones about what a bad idea it was, a revelation that didn’t hit until after the voting began: “I suddenly realized that I had set myself for an enormously difficult editorial task if the kid didn’t survive.” Y’think? (Naming the series “A Death in the Family” probably wasn’t a wise move, either, especially if there was a chance that he wouldn’t die.)

|

The final vote was 5,343 in favor of killing Robin and 5,271 in favor of saving him. A fairly close race, to be sure, but sheesh. That’s still a majority of votes for death.

A media firestorm ensued, focusing a little less on the ghoulishness of the entire process and more on the fact that the people who didn’t currently read superhero comics yet had grown up with the characters (or the 1960s television show) didn’t realize that the Robin that was killed wasn’t Dick Grayson. An oft-syndicated New York Times article from November 10 of that year did make the distinction between Grayson and Todd, so they get points for that, but they also hilariously referred to Frank Miller’s recent series as The Black Knight rather than The Dark Knight. Maybe they were fans of the pinball machine.

BONUS! Evangeline Lilly for Live Links (2005)

800-210-1010

Charge: The first hit’s free.

Celebrity hotlines had largely ceased to be a thing by the 2000s – chalk one up for the internet! – and the ever-present singles lines now ruled the landscape. This commercial that was probably filmed right before Evangeline Lilly scored the Lost gig. Can’t blame her for paying the rent during the lean times.