TR Review: Nosferatu (1979 German-Language Version)

|

1922’s original Nosferatu holds an iconic place in vampire lore. It was the first filmed version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, albeit illegally – the Count in it was named Orlok, though he’s been retconned to “Dracula” in the subtitles of some video versions. And it was the first instance of vampires in mainstream fiction bursting into flames upon contact with the dawn’s light – Stoker’s Dracula gets around fine in the day; he just has minimal supernatural abilities, and prefers to sleep. On the other hand, subsequent versions leaned toward a sexier count – director F. W. Murnau’s version, as played by Max Schreck, resembles a shaved rodent, and has only been duplicated subsequently by projects explicitly paying tribute. The TV Salem’s Lot, for one (against Stephen King’s wishes), and Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake.

Had everyone been on the Internet in 1979, no doubt fans would have railed against the notion of remaking such a classic, but as his more recent take on Bad Lieutenant can attest, Herzog (a) doesn’t give a shit and (b) wants to do something totally different with the concept anyway. By the time it’s done, his Nosferatu is at least as much a tribute to surrealist pioneer Luis Bunuel as it is to Murnau.

It’s also fair to say the original has dated badly in some areas – the fast-motion it used to make the Count seem superhuman now makes him come off as a Keystone Cop.

|

Herzog almost blows his load, horrorwise, extremely prematurely. The first sequence in the movie is a slow pan across what appear to be real, dried-out corpses…fully naked, and just to prove it, he lingers on dessicated labial lips long enough to rub it in. Sex and death combined in the most horrific way, making the point…and then swiftly being tossed aside as merely a nightmare being had by Lucy Harker (Isabelle Adjani). Yes, like many other Dracula movies, this one condenses and simplifies the core characters down to Jonathan Harker, Lucy, Van Helsing, Renfield and Dracula; Mina is here but as a minor character, a friend to Lucy who exists just to die. That’s fine: Herzog isn’t really that interest in the mechanics of Stoker’s plot, which often feel obligatory and cumbersome.

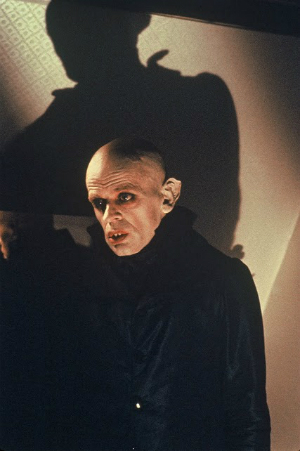

What appears to be at work here is more a systemic critique of European aristocracy and privilege, with Dracula (Klaus Kinski, born to play this role) as its true face: a hideous, loveless immortal from old money who wishes to die but cannot, even as he brings the plague across Europe, and the rich who prepare to die from it have lavish banquets in the streets among hordes of rats. Before Harker (Bruno Ganz, whom you know best nowadays as Internet-meme Hitler) leaves his hometown, the score constantly recycles annoyingly happy tunes played just slightly off-key. Said score turns ominous into Transylvania, and then is mostly replaced by an on-camera gypsy boy badly playing the violin once Harker realizes what Dracula is up to.

|

Herzog also reverses the sexual dynamic of so many vampire films, with a genuinely feminist Lucy who makes Bella Swan look like the idiot she is. [SPOILERS for a 1979 remake of a 1922 film in the rest of this paragraph] Rather than being seduced by the ugly bloodsucker, she tempts him, and he is so besotted with the brief illusion of love that he ignores the rising of the sun. Hers is the only victory; Van Helsing, played as a fool for most of the movie, stakes the Count and is accused of murder, but with most of the town dead or evacuated, there is nobody to take him to jail, nor a jail to take him to, so is ushered off without a destination or a guard. Harker, meanwhile, begins to show the full effects of Dracula’s bite and becomes his successor, implying that even with the heart of the rotting aristocracy finally gone, a successor is immediate and inevitable.

|

There’s a tangible reality to the film that few vampire movies have: without matte paintings or CGI, it feels free of fakery. Castle Dracula consists of actual ruins, and Harker’s house is fairly normal; the peasant lodgings along the way feel actually lived-in rather than any gothic creation. The only caricature here is the vampire himself, but Kinski inhabits him as a Gollum-like addict/pervert who is as tragic as he is nonetheless evil.

Like the 1930s Universal Dracula, which shot a Spanish-language version simultaneously on the same sets, Herzog’s was filmed in both English and German. The German version, less-seen in this country, is the one that is currently traveling with a new 35 mm print, and available online at Fandor.com (which also has the English language version. As I watched this via an online screener, I’d be hard-pressed to discuss the film quality, except to say that it did not appear to be lacking relative to others I’ve seen on my computer monitor.

If it comes to your town, check it out, and don’t fear the subtitles – the dialogue isn’t that elaborate to begin with, and you probably already know the broad strokes of the story anyway.