TR Review: The Director of Alien Resurrection Has a New Movie out and Nobody Was Told

|

Look, I know Alien Resurrection is pretty much undisputed as Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s worst film, but if I put “Jean-Pierre Jeunet” in the headline instead, guess what? Most of you would be saying, “Wait, where do I know that name from?” instead of “Why don’t you just call him the director of Amelie and City of Lost Children, jerk?”

Search engine optimization, folks. It makes for weird credit prioritizing sometimes. Point is, that movie aside, Jeunet is renowned as a highly imaginative, visually stylish director who even brings touches of fantasy to realistic settings like the trenches of World War I in A Very Long Engagement. Even when he fails to reach the heights of his masterpiece Amelie, his movies are worth watching just to see what he’ll do. Yet his latest one, The Young and Prodigious T.S. Spivet, has been quietly dumped into out of the way theaters in New York and L.A., without reviewers even being notified. This is presumed to be not because of its quality, but due to an argument between Jeunet and distributor Harvey Weinstein.

I’ve seen it. And if you have time and the ability to actually make it to a theater where it’s playing, you should too.

It is indeed a shame that what ought to have been a solid comeback film for Jeunet is getting dumped like this in U.S. theaters, not just because it’s hard to find but also because the movie was made for 3D, and the venues you’ll find it at will probably not be projecting it as such. This isn’t just some action movie jacking up the price with a gimmick, either – when you’re watching the film, it is very clear how certain things were specifically conceived with the added depth and pop-out factor in mind, and highly frustrating that they cannot be viewed as the auteur intended.

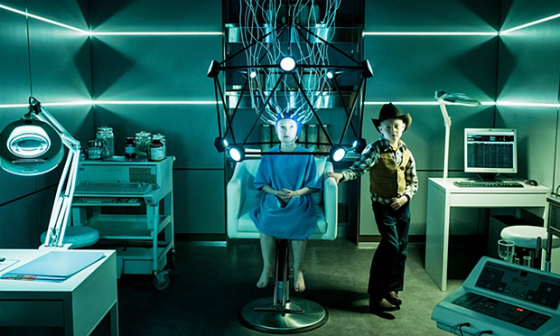

And before you yell, “Get to the point!” I will. T.S. Spivet, based on a novel by Reif Larsen, is set in an America similar to the fantasy Paris of Amelie – it’s the U.S. as imagined by a Frenchman raised on cowboy movies, ’60s sitcoms, production code-era movies and picture postcards. The T.S. of the title, played by Poltergeist‘s Kyle Catlett, is the genius child of a taciturn cowboy (Callum Keith Rennie) and an obsessive entomologist (Helena Bonham Carter). Inspired by a college lecture he sneaks into, T.S. invents a perpetual motion machine and sends his blueprints to the Smithsonian; when they call to tell him he’s won a major award, he lies and tells them that he’s T.S.’s son, then plans to travel cross-country to Washington DC to accept. By himself.

Along the way, he looks at beautiful scenery, stows away in a Winnebago that’s aboard a freight train, talks to his dead brother, hangs out with a hobo (Jeunet regular Dominique Pinon) and a trucker (Julian Richings). Once he finally makes it to the Smithsonian, he must decide whether to continue lying about himself or risk the truth coming out – including some truths he’s been hiding from us, the audience.

|

This is where my criticism may get weird – the notion that I would complain that a movie starring a kid needs to be more sentimental is practically an alien concept, like saying Carl’s Jr. puts too many things on their burgers. Yet a morsel of pathos would have helped the film’s midsection, which feels dramatically inert. T.S. tells us that he feels unloved by his father, and we know he has a brother who died young, but he says these things so matter-of-factly, and so seemingly unburdened by them, that they lack heft. If it felt like Jeunet were deliberately suppressing displays of these emotions while hinting that they’re below the surface, it’d be one thing, but it feels more like he just forgot to show us anything of the sort. In the movie’s last act, the heart emerges, and helps us to feel like something has been earned – but rather than a suckerpunch that blindsides, it feels like one tasty drop of juice wrung out of an orange that has been squeezed for hours to no prior avail.

|

Which isn’t to dismiss the movie itself – just the degree to which it may or may not move you. Jeunet’s more interested in the way T.S. looks at the world around him, all vivid colors and designs that seem like they came out of a carnival funhouse version of the United States. Sometimes as he looks at things, he imagines designs – the book included doodles in the margins, which Jeunet represents as floating notebook pages with animated diagrams on them, hovering above the objects that are inspiring them in what was probably a great 3D effect as originally filmed. And speaking as a half-European who takes a lot of crap for my other half from relatives, I say it’s nice to see a European look at this country which doesn’t make us into reflexively anti-science dumb cowboys, but rather extolls cowboys who give birth to budding scientists. Like Wim Wenders, Jeunet reminds us what’s great about where we live, even as he knows that we know he knows it isn’t all real.

But it doesn’t have to be. Movies are better than reality precisely because they don’t have to be bound by rules and facts and actual history, and few filmmakers paint the world they’d rather see on top of what exists better than Jeunet (one of Alien Resurrection‘s failures was in hiring such an optimist to make an essentially pessimistic film). In the character of T.S. Spivet, the director has found a representation of that philosophy, with one addition – this boy whose mind literally superimposes ideas over reality has the power to make the fantasy version real if he works hard enough at it, and by implication, so can we.

It should have been Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Hugo, a 3-D art film to impress critics and families during holiday/awards season. Instead, it may be his Idiocracy – a studio-buried cult classic few saw in its first run release, yet that everyone talks about today.