The Ten Best Fantasy/Sci-Fi/Horror Novels You’ve Probably Never Read

Not every book that deserves a cult gets one. Some tomes get bad reviews (or, far worse, no reviews at all), sometimes publishing houses on their last legs leave whole printings to languish in warehouses, and some books, whatever their merits, are simply hopelessly out of sync with the fashion of the times. They go unchosen even if they make it to the stores, and the membership of their authors’ cults number in the dozens. It all leads to a philosophical question: if a book rolls off the press and no one reads it, does it make a sound? In any case, if you have any of these curios on your bookshelf, you have truly impressive Nerd Cred:

1. Desdemona’s Star by Kevin Newman (1972)

|

Despite its potential for sci-fi/drama club geek crossover, this paperback original failed to catch on as a sort of Glee in space. It concerns a company of actors whose spaceship has broken down while they were performing Othello for mine workers on a distant desert planet. They manage a lift to their next gig with charter captain Mack Ward, who soon notices a ship following them – the theater ship, seemingly empty and pilotless. It turns out that their performance was witnessed not only by the miners but by an incorporeal alien capable of manipulating the desert sands in lieu of a body. This being fell in love with Bianca Healey, the actress playing Desdemona, thought her murder was real (La Healey having disappeared into seclusion with a migraine after the show), damaged the spaceship to prevent Iago’s escape, and then animated it to pursue and exact revenge on the poor guy playing Iago, and upon the Captain seemingly abetting his flight. Said Captain has, meanwhile, fallen in love with La Healey. Action, suspense and improvisation ensue.

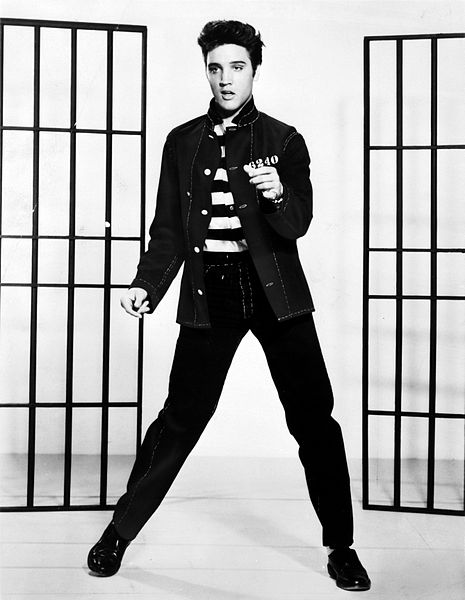

2. Corpus Elvis by Warbeck Perkins (1988)

|

Sometime in the mid-21st century, according to this bit of late-’80s snark, fans of the King of Rock and Roll began to regard their idol as another incarnation of God. This led, a century or so later, to strife in the now theocratic south, as war flared up between the Presleyan Republic of Tennessippi and the Holy Evangelical Confederacy of Georgiabama. The “Left-handers” – a shock troop of Evangelicals who show their faith by, in accordance with Biblical teaching, putting out their right eyes and cutting off their right hands, replacing the latter with bayonets in the shape of a Cross – march on the Holy City of Memphis, and the defeated Presleyans work frantically to evacuate the Relics of Graceland to a new planet, Corpus Elvis. Perkins – no relation to Carl – died of heart disease in 1999, but is said to have written a sequel, Tupelo, as yet unpublished (though an infamously bad low-budget movie version played a single screen in New York for about a week in 1990).

3. Little Ricky’s Mother by Suzy Berger (1981)

|

Berger was a senior at Boston’s Emerson College who had been given an assignment to write a horror story in the style of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. An animal lover and an occasional volunteer for the Alliance Against Laboratory Cruelty (AALC), she was inspired by the notorious ’50s-era animal psychology experiments at the University of Wisconsin, where rhesus monkeys were given surrogate mothers to which they bonded. In Berger’s tale, reset in Florida, Little Ricky clings to his cloth and metal “mother” Lucy even when she gives him electrical shocks, and even when spikes spring out of her. But when Little Ricky outgrows his usefulness and is slated for euthanasia, even the inanimate Lucy’s maternal instincts kick in, and she goes into ferocious protective mode, using said spikes and electrical shocks on a variety of laboratory sadists before taking her “baby,” with the help of a kindly young lab assistant, to a new life with a feral Rhesus troop in the Everglades. Berger’s story ultimately ran to novel length, and the AALC published it in paperback and handed it out for free at the organization’s rallies and events.

4. From Ancient Grudge by Deborah Capelatti-Montecchi (1981)

|

Rare and expensive on eBay is even a beat-up copy of this, surely the most obscure of the early Bantam Star Trek paperback originals. Little more than a novella, it’s a sequel to the Original Series third-season episode “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” about the ongoing hatred between the two-tone denizens of the planet Cheron: Lokai, who’s white on the right side and black on the left, and Bele, who’s black on the right side and white on the left. As you’ll recall, the show ended with Bele chasing Lokai through the transporter of the Enterprise down to the surface of their planet, which had seemingly been completely depopulated by racial strife. In this sequel, we learn that upon reaching the surface, they discovered that while they were away chasing each other around the galaxy, Lokai’s son and Bele’s daughter had fallen in love and produced a child – the coloration of which remains a mystery until the book’s final pages – and fled the planet in a spacecraft to look for a safe haven elsewhere. Bele and Lokai are instantly turned into grim, infanticide-minded allies by this knowledge; they take off together and leave a trail of mayhem across the Federation in search of their grandchild. McCoy and Uhura are drawn into the story, but they’re secondary characters in this combination of The Searchers and The Sneetches.

5. Lamprey Man by Drew McTigue (1989)

|

Also published under the titles Invasive Species and (in the UK) Misery Bay, this is one of several lurid paperback shockers cranked out in the ’80s for Cassowary Books by the prolific McTigue, along with Great Legs (giant centipedes), Pray for Brookville (praying mantises the size of horses) and Midnight Vermin (cockroaches the size of baguettes). In this one, two dimwits are hired to dispose of industrial waste and do so by dumping it into a lagoon on the Lake Erie shore. They spot an investigative journalist photographing them, kill him and dump his body into the water in the same spot. Later that night the journalist emerges from the lake with the head of a lamprey on his shoulders. He leads an army of the parasitical critters, now adapted to crawl onto Terra Firma. They take revenge on the dimwits, the industrialist, and the lover of his ex-girlfriend, sucking all the fluids out of their bodies. Eventually, he and his lamprey followers amalgamate into a titanic uber-lamprey which rampages in the streets of Erie.

6. Gilamanster by Barry Stephenson (1991)

|

Also published under the title The Mascot, this potboiler set in a small town in Arizona concerns a desperate-to-fit-in kid who wears the costume of his high school’s football mascot, a Gila monster. The rich kids hire him to entertain in costume at a party after the big game, but it’s a Carrie-style prank: once he’s in the suit, they stuff it with real Gila monsters, stolen from the lab of the creepy science teacher. The poor kid plunges into a nearby desert lake, but the rich kids don’t know that the science teacher was working on a project for the government. The mascot re-emerges from the water soon after, fully equipped with the lethal venom and strength of a real Gila monster, and breaks up the rich kid party. Some readers have observed a similarity, both of content and of style, between McTigue and Stephenson.

7. Pearworld by Ian Bricker (1994)

|

How many fantasy novels have an art critic for a hero? This one, written, as it happens, by a veteran art critic, features a critic who’s invited to the home of a famous painter whose work he regularly trashed in print, and who has recently died. The great man’s sexy widow gives the critic a real pear which, she claims, has been taken out of one of the painter’s still lifes by a mysterious process. Unable to resist, the critic eats the pear, and soon finds himself in a parallel (pear-allel?) universe where abstract color patterns walk down the street and strike up conversations with you at diner counters, and where a shopping cart stack in a store parking lot becomes a menacing dragon.

8. Malcontents of Mars by Mitchell Tiemeyer (1937)

|

First serialized in Likely Stories, this yarn featured square-jawed hero Bolt Willard, who was sent by his Uncle, the President of AriesCorp, to investigate the possibility of union organization in the company’s Martian uranium mines. Sure enough, with inside information from his faithful sidekicks Tom and Chin, Bolt learns that agitating is going on, but that the miners are being duped by the sinister power-monger Abraham Tong, who hopes to become King of the Red Planet. At the end, Mars is returned to the benign governance of AriesCorp. In addition to his pulp adventures, Bolt Willard was a modestly popular radio hero and was featured in a 13-chapter Republic serial, but it’s been hard to find since Tiemeyer fell out of favor shortly after Pearl Harbor.

9. The Stone Thief by Arthur Addison Goff (1926)

|

“Even the monks of the Cattail Abbey, the youngest of which was over three hundred years old, could not say when The War had begun. If you asked the eldest of them, Brother Bernard, if he remembered the beginning of The War, he would say yes, but since Brother Bernard said yes to every question he was asked except whether he would like some more mole pudding, and never said anything else, his testimony was regarded as neither reliable nor helpful.”

The payoff to this opening of Goff’s only published novel is that we never get another word about the monks of Cattail Abbey. The War started a long time ago; that’s the point. Touches like this are found throughout the tale, creating an immersive sense of a wholly imagined world. Though claimed as a minor influence on Tolkien, this high-fantasy epic was an abject failure upon initial publication, and has never really undergone a major critical reassessment.

The War is a centuries-long siege, with the forces of King Corambis permanently encamped around the walled city of Lowgrippe, ruled by King Lannius. The title character is One-Hip, a street urchin chosen, because he’s so skinny, to slip through a newly-discovered catacomb into Lowgrippe and steal the magic stone that will allow Corambis to take the city. Once inside, One-Hip is captured and imprisoned. Falling in with fellow prisoners Stekli, a Dionysian priest who has his own agenda for the stone, as well as Stekli’s beautiful young apprentice, ZuZu, One-Hip is soon tempted to change his plans…

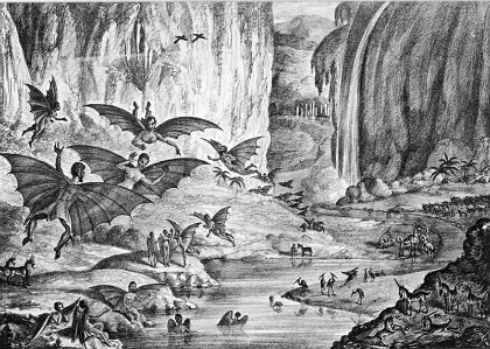

10. The Rise and Fall of Scabbopolis by Lucian Conavaloff (1921)

|

It’s said that the unrealized project dearest to legendary Battleship Potemkin director Sergei Eisenstein’s heart was a film adaptation of this early Soviet satire of capitalism. The capitalists are here depicted allegorically as a clan of skin mites building their empire, Scabbopolis, on the forearm of a dutiful worker in a factory. The itch they cause him eventually leads to their destruction, by way of a Soviet-developed ointment. The book wasn’t translated into English for many years, in part because, in emulation of Conavaloff’s beloved Eugene Onegin, the story was told entirely as a series of “Pushkin Sonnets” (ababccddeffegg). A translation was finally attempted in the ’50s by the Russian-lit scholar William Helwig Nicholson, resulting in such renderings as this (when the initial mites meet)…

One inch per hour I perambulate

In search, like every searcher is, of love,

Across my epidermal grand estate,

Past mighty tree trunks, fading gray above.

Beneath this countryside, the thudding beat

Of that great salty river drums my feet,

And tints the leather prairie pink, and heats

The burrows into which my love retreats.

And there she is! From me she cannot hide!

No wrinkle in this continent, no pit

That hair-tree hath eschewed, no split

Half-patched by scab detains me from her side.

Close nestled in this crevice, we embrace,

And found a colony for all our race.

Later, when destruction of Scabbopolis is imminent, the Mite Queen gives her husband this proud, wistful farewell…

Good patriarch to all my broods, my spouse

And ardent love, I sense the Ointment’s day

Descending fast upon our noble House,

Demanding we to Disappointment pay

The dues of grief that all who seek to loom

A weave of generations must assume.

Our kind hides not within the scarlet deep

Of this great fleshy planet. No, we creep

Exposed across the open, daylit plain,

And there raise up our cities to the sky,

And risk the notice of that jealous Eye

Who sends us death in tides of oily stain.

Does he suppose the Skin on which he lives

And freely scars, unendingly forgives?

Unable to find an academic publisher for this work, Nicholson finally got his translation released in America by Belfry Books, on the basis of some risque passages. As for Conavaloff, like many other promising writers of his time he fell out of favor with Stalin – his mites were too sympathetic, maybe – and died in obscurity, with the result that his book is even less known in Russia than it is in the U.S.