TR Interview: Kurt Johnstad, Cowriter of 300: Rise of an Empire

|

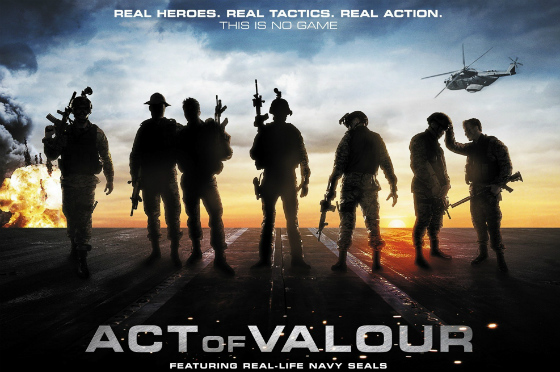

Zack Snyder may be the name you most associate with the 300 movies, but Kurt Johnstad is the guy who wrote both of them in collaboration with the director. A former assistant director and key grip, Johnstad has an unspecified but long-standing relationship with the military, and is also known for the “Navy SEALs playing themselves” movie Act of Valor.

Writers don’t generally do the same amount of press as directors and actors, but on this day, Johnstad prepared himself for interview glory.

Tip of the hat to Gallen_Dugall for some of the question suggestions.

Luke Y. Thompson: They don’t usually bring the writers to the junket. Is it awesome to be at a junket, or is it exhausting, or both?

Kurt Johnstad: No, no, it’s not exhausting. It’s always good to talk about stuff. Working with Zack, I think we have a familiar kind of – we’re familiar with the world, and yeah – it’s good to be here!

LYT: It’s taken longer than you’d expect to make a sequel to such a big hit as this. Was any part of that getting the script right? Or were you like, “Come on guys! I’ve got these ideas waiting to go! Just green light it!”?

KJ: No, it really it went down how it formatted, the flow of it, was that Frank Miller, everybody wanted to know, is there a sequel? What is it? Things like that, and Zack really kind of stepped back from it, let it kind of sit for a while, because he thought it might just be a single movie. And then Frank came to us and said, “Hey, I’ve got this idea. This is a story that I’m really interested in.” Kind of a parallel time-line. He sent us an outline, and showed us some frames that he was drawing of the graphic novel called Xerxes, and then basically, that was it. Once we had the blessing from Frank, we started moving forward, thinking about it. And then the studio said, “OK. Let’s do it.”

|

LYT: Xerxes the comic book hasn’t actually come out yet, right?

KJ: I have not seen a published copy. I’ve seen it drawn, but I haven’t seen it.

LYT: So you’ve seen it complete, in its entirety?

KJ: No, I’ve seen probably – I mean, I’ve seen a lot of drawings, but a lot of times they’re out of sequence. But yeah, I’ve seen a lot of it.

LYT: Is it quite different? Because obviously it’s called Xerxes, but in this movie Xerxes is in the beginning and the end, but he’s only a major player behind the scenes, and not so much…

KJ: Uh, I think there’s a lot of the aspects of how Xerxes came to power, being a God-King – all of that is there starting in Marathon. Those things are all Frank’s influence, definitely.

LYT: How faithful to the history did you feel the need to be? Did you do a lot of research, or is it like, because there’s a fantasy level to this, we can pretty much stick to what Frank has?

KJ: I think that we did do research. Obviously, the battles, the dating is correct. All the players, the main players – Themistocles, Artemisia, obviously Queen Gorgo – those people all existed. We didn’t play with – the battles actually happen on the exact same day or coincide with what’s going on in the north of Greece at Thermopylae, during the hot gates. So all those things are solid in history, and of course we’re creating characters, like the father and son story – just different things to flesh out the story. But it’s also a story that does not have to be – it’s based on history, but it’s not bound by history, because it’s through a storyteller’s eyes.

|

LYT: On the flip side of that, in almost any other movie, if you had a guy walk into a pool and come out a nine foot androgynous giant in a Speedo, you’d probably get notes saying, “People won’t understand this. You’ll need to explain it.” But in this movie, you totally don’t have to – everybody just gets it. Is that really liberating to play in a sandbox like that?

KJ: Yeah, it is. I think that there’s a luxury, and that’s one of the great things of using the device of the storyteller, is that you can exaggerate and make a good story out of it, and if you’re bending truth or shaping the truth, or even just recreating things that, because you’re basically talking about Xerxes, and you’re creating this mythical character for a free Greek’s eyes – because, to them, that was the enemy, so of course it was going to be a monster and a giant, and somebody that they had never seen or were afraid of, and of course people do that when they’re afraid of the unknown, things like that – they start to exaggerate.

LYT: As far as the storytelling device, the first one was very clearly sort of all a campfire tale, and kind of ended that way. This one, most of it is Gorgo telling the story on the boat, but then it goes past that point. Was there ever a worry about that, that it didn’t somehow end with her narrating it? Because then it takes out the “Oh, this was just a story,” and it was like, “This is kind of more literal.”

KJ: No, no; not at all. I think we used kind of the bookends and make it work, and then we kind of pushed past the bookends, because the hope is the movie does well, there’s always room to make the fall of these heroes and villains into their next movie.

LYT: Yeah, it seemed like there was pretty clearly a segue into a next possible one. Is that something you guys have mapped out?

KJ: That is something that certainly Zack and I have a very clear idea of what we would like to do. If asked, we will sit down and start writing.

|

LYT: One of my regular readers is a real historical buff about these ancient military campaigns, and he came up with a couple of things that he wanted me to ask. He said that traditionally, the ancient Greeks never spoke highly of their foreign adversaries, but Artemisia was a big exception. Did that inform her portrayal in the movie?

KJ: Yeah, I think that she was revered and also feared. She was, from what I know of the history, she was a Greek who then turned and was fighting for the Persians. The interesting thing about that is that this was a time where usually men took to the battlefield under their own free will and volition, from the Greek side. They weren’t under – they weren’t slaves, so they weren’t fighting for a king, necessarily, except the Spartans, and they really looked at her as a terrifying, terrifying enemy to face. Definitely they respected her – Themistocles did, for certain.

LYT: He also said, and it wasn’t quite portrayed in the movie this way – Themistocles initially exaggerated the threat in order to raise – to get the military budget raised, but then that higher military budget actually ended up building the fleet of ships that actually did win the battles.

KJ: Yeah, historically, that is true, and we weren’t able to service that. But in a character, as far as Themistocles as a character, he was known as kind of the silver – the silver snake or the silver serpent of Athens. He had this ability to kind of work both sides of the aisle. To say one thing – he was very manipulative as a politician, and then he would get what he needed and kind of force multiply that into his military campaigns.

LYT: When you’re writing this with Zack for a different director, do you say in the script: “Here it speeds up,” “here it slows down,” “here it pauses” – that kind of thing?

KJ: No. It’s funny that you say that. Initially, I wrote the script for Zack to direct. And we were in the middle – the process of writing it, when he came to me and said, “Hey, there’s an opportunity – Chris Nolan, I just had a meeting with him, and Chris just asked me if I would be interested in doing Man of Steel.” And then he went to the studio and he had a very good meeting, and then he became the director on that project.

He said, “I know we’re in the middle of this, and this is crazy,” and I was like, “Zack, this isn’t – we don’t have to have a conversation about this. You’re going to go do Superman, and we’ll just figure out what happens with this movie.” So I guess to answer your question, we were writing it for Zack to direct, we were nearly finished when he decided to go do Man of Steel, but we completed it as if Zack were to direct it. Yes, in the draft, there are things like, in all caps, “TIME SLOWS.” And then you punch in on that moment, whatever – “Sweat dripping off helmets,” or “Blood dripping off…” and then time ramps back. You will see that in the draft.

|

LYT: When you’re writing big battles like that, how much of it do you put on the page, and how much do you leave to the director? Are you, like, “Athenian #51 clashes with Persian #16”?

KJ: No. No. I try not to enact ideas consciously. I mean, I do it in all the scripts that I write, but we try not to – we would write something like, “Bronze and wicker clash; the Persians and the Spartans fight; it’s a ballet of violence and death.” You give kind of the broad brush strokes, but if you give too much detail, you start to paint yourself into a corner, in the sense of when the fight choreographer is there, the time of day you’re going to shoot it. You can give some specifics, but if you get too narrowly specific in the architecture of action, it usually, in a film like this – we would have boats colliding, or things like that, or horses running across the decks, but you don’t want to go, “He turns. He lifts. He picks it up.” It eats up too much page to describe that kind of action, so you just keep it general.

LYT: I’ve got to ask specifically then – the lightning bolt in the horse’s eyes – the hoof then comes down, crushes the head – tell me you wrote that!

KJ: I did not write that.

LYT: You did not write that beat?

KJ: No. Actually that originally – that’s all in the interpretation of, once Noam had decided the Marathon scene – I did not write that, because Marathon, it wasn’t raining, but Noam said, “God, it would be really cool if it was raining, and it was muddy, and I’ve never really seen that, it’s more like Henry V – Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V.” I was like, “OK, that’s awesome.” And so he went with that just artistically – “It’s going to be raining, there’s going to be thunder and lightning.” And that’s really, in that moment, it’s kind of Zack and Noam are going “OK, it’s going to be this kind of movie.” Directors make decisions off what I write all the time.

LYT: When you did Act of Valor, was that because the military loved 300 so much that they sought you out?

KJ: [chuckles]Uh…you know, I came to Act of Valor in a very interesting way, and I have a very close, long-standing working relationship with the Naval Special Warfare community, and I’m friends with a lot of that community. So there was a captain who was part of the director of Special Warfare recruiting – he came to me, and he knew that I had written 300, and he introduced me to the Bandito Brothers, who ended up directing Act of Valor, and he said, “Hey, I know the guy who wrote 300. Would you like to meet him?” I met with Scott and Mouse, the directors from Bandito Brothers, and we created a movie, and then they went and filmed it. Yeah.

|

LYT: Do you feel like there’s a lot in common with modern military versus ancient? Has it changed a lot, or not so much?

KJ: I mean, except for the hardware that they use – no. I think it’s the same brotherhood, it’s the same “I’ll go shoulder to shoulder, I’ll fight that battle, go over that hill, take that mountain, I will die in your arms.” It’s the exact same ethos – warrior ethos – that is from the guys that are serving – the men and women, it doesn’t matter – that are serving now in any military, or the guys that were in World War II, or all the way back to Marathon. It’s the same kind of – you know, something happens in combat that really defines men, and women, but specifically in this sense, the warrior spirit, the esprit de corp – it’s the same. It travels across the timeline of history.

LYT: A lot of people – colleagues of mine – read a lot of political subtext into the first film. Were they reading too much into it? And if not, is there some in this new one?

KJ: No. I mean, I think everybody finds what they want to find in works of art and film and music. I mean, Zack spoke about this earlier today, where in press conferences for the last film, people would ask him, “Did George Bush really direct this film and you just put your name on it?” The idea is that people are going to look for the things that satisfy them in a film, and things that maybe they push back on. But there’s no bigger, broader, geopolitical conversation.