12 Revelations From the Makers of Starchaser: The Legend of Orin in 3D

|

| Movie Poster Shop |

Ask most science-fiction fans to list their favorite genre movies of 1985 and they’ll name Back to the Future, Brazil, Cocoon and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Ask me and you’ll hear the same list, plus one extra title… Starchaser: The Legend of Orin. I first saw the film theatrically when it premiered on over a thousand screens in the fall of ’85, and its cutting-edge mix of traditional and computer animation blew me away. Here was an original, independently produced space opera, filled with dazzling 3D imagery and an adult storyline! What a pity, then, that Starchaser never found an audience. As its 30th anniversary approaches, I spoke with the film’s director/producer, Steven Hahn, and its screenwriter, Jeffrey Scott, about the challenges of bringing this groundbreaking 3D adventure to movie screens.

1. Escape to the Stars

|

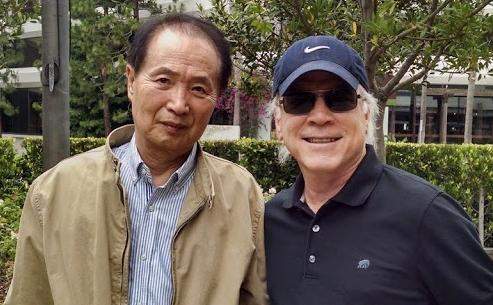

| Matthew Chernov |

Topless Robot: Steven, you’d been working in animation for quite a while before directing Starchaser, correct?

Steven Hahn: Yes, I’d been working in television animation and owned a rather huge facility in Korea. I’ll tell you why I came to direct and produce this film. It’s not something you might expect. During the off-season, I had nothing else to do! When you own and run a big studio, it’s difficult to sit around and pay everyone a salary when there’s no work. So, I had to do something, and I thought, why not make an animated film? That’s how I started. I really didn’t know what I was getting into. I’m not someone who was dreaming of doing 3D, nothing like that. It just started as a business solution to cover my off-season people.

TR: Jeffrey, how did you get involved in writing Starchaser?

Jeffrey Scott: Well, my original title was Escape to the Stars. Steven contacted me and said he wanted to make an animated feature, and I think he chose science-fiction because after Star Wars the market just exploded. Everybody was doing sci-fi, and I had always wanted to make a realistic animated film. Something that combined an adult story with animation, you know? So I came up with the concept for Escape to the Stars a.k.a. Starchaser.

2. The Danger of Proportional Space

TR: Did the screenplay go through many drafts?

JS: Not really. The biggest challenge I ran into was formatting.

TR: What do you mean?

JS: Well, this was in the early days of computer printers. If you remember, they had dot matrix models, and then the new daisy wheel machines came out. The daisy wheels spun around and would slap-slap-slap the words on the paper. Back then, I had a Xerox computer, which was basically just a word processor. It was the size of a small refrigerator! And it had what’s known as proportional spacing, which compresses everything to fit the page. We don’t even think about this stuff today. So I wrote the screenplay in proportional spacing. You probably know that each page of a screenplay equals approximately one minute on screen. Well, that goes out the window with proportional spacing!

TR:How long was your script?

JS: The draft I wrote was 135 pages, which already would have been a 2 hour and 15 minute movie. But since it was written in proportional space, it was even longer than that! None of us noticed until Steven put it into production and had it storyboarded. That’s when we realized how massive it was!

SH: Like I said, I didn’t know what I was getting into (laughs). Jeffrey brought me a script which I was very excited about. But when we broke it down, scene by scene, it was huge! So we had to cut it down.

TR: Jeffrey, did you supervise the script edit?

JS: No, that was left up to Steven and the storyboard artists. The good thing was, I’d written so much, you could lift whole scenes and not change things too drastically. It’s a very episodic film, so if you just remove some episodes it still works. For instance, there was a scene where Orin was in a bar, and he was playing three-dimensional pool, and the balls were flying all over the place! It would have been a fun scene in 3D, but it had nothing to do with the plot so they had to cut it.

TR: So Starchaser wasn’t a spec script?

JS: No, I wrote it specifically for Steven. I was a successful television animation writer and Steven had produced some of the series that I wrote for ABC, CBS and NBC. And he came to me and said “I want to do a feature, would you write it?”

SH: I’m very proud that Jeff’s screenplay has a beginning, middle and an end. It’s an epic story!

3. The Three-D Stooges

|

TR: Jeffrey, did you have any interest in 3D before you wrote Starchaser?

JS: It’s a small world that Steven came to me to write this because my father, Norman Maurer, invented 3D comic books! You know, with the red and green filters? He was a successful comic book artist, and his partner, Joe Kubert, was one of the masters. Together they worked out the details and brought the concept of the left and right eye to comics. Each issue came with a set of cardboard glasses. So I grew up with 3D. In fact, here’s another connection. My grandfather was Moe Howard from The Three Stooges.

TR: You’re kidding.

JS: No! And The Three Stooges did one of their shorts in 3D! With Shemp, in the ’50s, they did a 3D comedy. So it’s like I can’t get away from this stuff! (laughs)

TR: As a fad that came and went over the years, 3D was often associated with cheap sci-fi movies. Were you concerned at all about using the gimmick for Starchaser?

JS: 3D was a jinx for years. It finally works now, since they’ve developed CG animation. Today’s computers can handle all the difficulties. When my father did 3D comic books, the first issue was a huge success. So all the other comic companies immediately got into the 3D business. But the fad passed and many of them went broke. There’s always been difficulty with 3D. Obviously, Steven had some extremely challenging experiences on Starchaser. You know, part of the problem is that 3D often gets in the way of the story. Because if you’re looking at the technique of the film, you’re not in the story. If you’re looking at the 3D and going “Wow! This is cool!” you’re out of the plotline. You might as well be at Disneyland. But now they’ve finally got it down to where it looks really good and we’ve seen it enough that there’s no “Wow!” factor to take you out of the story. We just watch it and it’s more real to us. But it took a long time to get there.

4. Emotional Reality

|

TR: Steven, what made you decide to shoot Starchaser in 3D?

SH: I thought that science-fiction worked best when everything seemed real to the audience. That’s the best way to evoke emotion. And the cartoony style of Saturday morning animation wouldn’t have done the job. So I wanted realism as much as possible. It’s much harder to draw realistic characters, but I thought it would render a more emotional experience. And then I thought, if we can create that realistic setting in three-dimensions, it would work even better! So that’s why I decided to do it in 3D. And so, I assembled the crew, including John Sparey as a scene planner in 3D modeling.

TR: Sparey worked with Ralph Bakshi on Fritz the Cat and Fire and Ice.

SH: Yes, he worked on our graphics program for about six months. And later, Bill Kroyer joined the crew in our computer graphics area to fine tune things even further.

TR: Bill Kroyer, the CGI artist on Disney’s Tron.

SH: Correct. On Starchaser, we had the first computer graphics program that actually had a pen that could draw in 3D.

JS: A digital plotter.

SH: It was the first time in animation!

JS: The ship in Starchaser was created that way. Never been done before.

SH: Yes, all the spatial movements were accomplished with that program. There was no other way we could calculate it correctly. So we really had some very difficult tasks.

5. A Daunting Production

|

TR: You said you had an animation facility in Korea. Is that where the film was made?

SH: Pre-production and post-production were done here in the United States, and some key scenes in animation, as well. But most of it was animated in Korea.

TR: How did you coordinate that in 1985 without access to email or Skype?

SH: Believe me, it was really daunting!

JS: I think the answer is… American Airlines! (laughs)

SH: Our monthly phone bill at that time was three-thousand dollars! And we constantly shipped footage back and forth. It was very difficult, because they’d animate a shot in Korea, and then send it over to the United States, and we’d view it in our screening room in 3D. Well, sometimes it worked correctly, and sometimes it didn’t! So we’d ask them to redo it and the process would continue like that, twice for each shot!

TR: Why twice?

SH: Our 35mm film was split across the middle. Top and bottom. Over and under.

JS: Left eye, right eye.

SH: For 3D, our cameraman would shoot an image for the top half of the film. And then we’d rewind the film and do the same shot again for the bottom half.

TR: So your 35mm frame was split horizontally, and it has the same movie on both halves, just slightly different?

SH: Exactly. Sometimes we’d have an effect, like a laser or something, and we’d have to go back and forth twenty times! Because if one frame is off, the 3D just doesn’t work. In the middle of all that, I thought I was crazy. I had, probably, about five million dollars of my own money invested in the film. But the budget turned out to be closer to fourteen-million. I thought it would take six months to complete. It took three years! The execution on my part is nowhere near what I wanted to do, because of the technical difficulties and the size of the production. I had quite a number of people on staff in Korea and quite a number of people here in the United States. At one time I had almost ninety people on payroll!

TR: Why weren’t the big studios making 3D animated films back then?

SH: When I finally finished Starchaser, Roy Disney asked me to bring the film to his screening room so he could see it. And even though he knew the mechanics of animation, he said “How did you do this?!” And then I realized why Disney didn’t make 3D animation. Because it was so difficult! Only crazy people would do this! There’s an old Korean saying… “Newborn puppy doesn’t fear the tiger.”

JS: It just becomes lunch! (laughs)

6. Chapter Eleven

|

TR: Starchaser was released by an independent production company called Atlantic Releasing Corporation. What were they like to deal with?

SH: They were very excited with my project! They were very helpful, really, beyond what I asked. I think they advanced some of our production budget, because, as you know, it grew over time. They really liked the project and let us do our work. But, when it was finally released in 1985, they didn’t realize, and I didn’t either, that 3D screenings needed new projectors in theaters. Also, the screen itself has to be silver, not white. If it’s not silver, you have to apply a reflective coating to it, because the image is darker by about thirty-percent. So it has to have more reflection, or else it’s too dark! Now, those two components are difficult for many theaters. In major cities, it’s not so hard, but everywhere else it caused a problem. Sometimes the new projectors didn’t work, or they didn’t prepare the screen correctly. So there were a lot of technical distribution problems. And then, two months later, Atlantic was sold to another company, and the new owners went bankrupt. Chapter Eleven! And a lot of filmmakers sued them, so Starchaser didn’t have a proper support.

7. No Margin For Error

|

TR: Did you use rotoscoping at all when animating Starchaser?

SH: No, no. We didn’t use any rotoscoping. I was working with Ralph Bakshi as a subcontractor, and he’d made films like Wizards with some rotoscoping. So I got to learn exactly what it actually does on the screen. But there’s no rotoscoping in Starchaser.

JS: That’s what made it so much more difficult to create. Steven’s animators were hand-drawing human characters and getting them to move realistically. It’s the most difficult thing there is because we’ve all seen humans move and know exactly what they’re supposed to look like. There’s no margin for error. But we’ve never seen Porky Pig in real life, so Porky can squash and stretch himself and do all kinds of things and we never question it.

8. Man-Droids and MacGuffins

|

TR: I’m a huge horror movie fan, so my favorite characters in your film are the half-human, half-machine Man-Droid creatures. They’re so wonderful and disturbing. Can you tell me about them?

SH: To you, disturbing is wonderful! (laughs) I thought they would be a very interesting addition to the story, so we added them. And I enjoy them, myself. They’re very creative.

TR: That scene is so effective because it happens as soon as Orin escapes from the mines at the very beginning. It’s an out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire moment.

JS: It becomes a be-careful-what-you-wish-for situation. He’d been told that there’s freedom up above, but what’s freedom? It’s a world that he doesn’t understand, and it’s so dangerous that now there’s a new level that he has to escape!

TR: Where did the idea for Orin’s mysterious blade come from?

JS: The blade was designed as an absolutely classic MacGuffin. Everyone’s after this thing, this blade. And a MacGuffin isn’t real. It’s useless. It just drives you forward. And that’s why I ultimately had the blade turn out to be nothing but Orin’s own psychic creation.

TR: It also hearkens back to the Excalibur legend.

JS: Yes, there’s a sword-in-the-stone element to it. But you know, these are the archetypical things that are just there so that people can better identify with them. When I was developing the plot, I wasn’t looking at any of those things individually and trying to work them in. My initial concept was, what would it be like to live under ground where the ceiling was so low that you could never stand up fully? That was my first idea. What kind of existence would that be? From there, I built all the rest. How would you find your way out? Well, you’d dig something up! My favorite line in the movie is “Never dig up, because up is Hell!” So I just reversed our own, standard religious viewpoint.

9. Rock and Roll Artwork

|

| Amazon |

TR: This may sound strange, but I noticed some visual similarities in Starchaser to the work of Roger Dean. He’s an artist known for the surreal album covers he painted for rock bands like YES and ASIA. Is there anything to that?

SH: Roger Dean? No, I don’t think I recall his name. But you know, I started planning the film over thirty years ago. We had a lot of artists on the project who were very dedicated.

JS: At the time I was writing the screenplay, publishers were producing very inexpensive art books filled with album covers and science-fiction landscapes. This was post-Star Wars. Well, I’d get those books as research material, and look at all the images to help color my imagination. And I’m sure that all the major rock artists, including Dean, were in those books somewhere. That kind of sci-fi psychedelic art was very popular.

TR: Changing gears for a moment, where were the voice actors recorded?

SH: They were recorded here in the US. I asked them to record in an ensemble as much as possible, because I wanted them to develop a relationship in their performance. We had rehearsals and then I recorded them. I had a lot of good help with casting the voice actors. They brought in a number of tapes for me to listen to. So we heard them all and I picked the right ones. Joe Colligan played Orin very well. And Carmen Argenziano as Dagg was an interesting character. They all worked so well together! I was very happy with the voices. The actors went beyond what I asked of them. They’d show up early and rehearse themselves, because they realized this was the first film of its kind in history!

10. Pushing the Envelope

|

TR: There are some surprisingly mature elements to Starchaser, particularly in regards to sexuality and violence. For a PG animated film, it pushes boundaries, especially in the scene where Silica, the female robot, is reprogrammed through her butt. Was this something you purposefully set out to do in the script?

JS: I wrote it as a live-action script. My viewpoint on Starchaser was just to write a good sci-fi epic. I had no consideration that I was writing animation. Basically, I wanted real characters in a live-action story. I pushed the envelope from a kid’s standpoint with a little sexual innuendo, but I didn’t write it just for kids.

TR: Did you get any notes back asking to tone it down?

JS: Well, I never got anything like that from the production side.

SH: The executives at Atlantic Releasing gave some advice, but it was always positive and encouraging. So we stayed within the PG boundary.

TR: Orin’s quest to free his people in Starchaser has a Moses-like aspect to it. I also noticed some subtle Christian elements throughout the film, including the moment at the end where Orin literally heals the blind by laying his hands on their eyes. Was religious imagery something that you deliberately added to the story?

JS: It wasn’t done overtly. I didn’t set out to add a Moses figure to the script, or any specific Bible imagery for that matter. I was just trying to tell a story. And at the climax, when the glowing figures arrive, what I was really saying was that we’re all spiritual beings. The scene where Orin heals his brother’s blindness was a similar thing. It was a way to show that there’s something going on beyond the physical realm. I admit it was a stretch. If I was to write the script today, I don’t know if I’d make his blind brother see again.

11. Where Are the Toys?

|

| Amazon |

TR: Was there any thought given to selling Starchaser toys? The ship and the characters seem like they’d lend themselves to merchandising very easily.

SH: Yes, we discussed it. However, Atlantic Releasing was going through Chapter Eleven, and then they were litigated. So everything stopped. I couldn’t do it myself, because I was running such a large crew in two countries. My hands were full and I was making creative decisions every day. Atlantic was very ambitious in the beginning, but they started to have financial strain and then bankruptcy. So, no toys.

TR: Aside from the DVD, the only other piece of Starchaser merchandise is the soundtrack CD. Who composed the score?

SH: Andrew Belling.

TR: He wrote the music for Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards, I think. How did you come to work with him?

SH: Through some sources, I don’t remember who. And he came to see me and composed some melodies and themes to make sure that we were in tune. The actual recording was done in London with ninety pieces.

TR: A ninety piece orchestra?

SH: Yes.

TR: Wow! That makes sense, because it’s a very symphonic score and really opens up the world of the film and lets it breathe.

SH: Belling’s music was very ambitious.

12. The Future of Starchaser

|

| Amazon |

TR: A few years ago there was talk of a live-action version of Starchaser. Is this something you’re currently working on?

JS: We’re still in the early planning stages.

SH: There were a couple of young writers who wanted to get the live-action rights to my film. I think they were working with the William Morris Agency. They said they would come up with a script within one year. Two years passed and still they had no script. After that, I said, okay, this may not be the right one. So we departed.

JS: Then we thought we’d just do it ourselves, rather than let someone else make it.

TR: The DVD release in 2005 was a gift to fans, but what about a possible Blu-ray release, or even a limited theatrical re-release? Any chance of that happening in the future?

SH: I have partners in Korea, and they’ve been working on a DCP of Starchaser. You know, a Digital Cinema Package. I’ve been there a few times to tighten and repair the film. After thirty years, there’s some dirt and things that needed to be cleaned. They’ve upgraded every frame. Back then, we didn’t have surround sound, so we added surround sound! That’s what we’re working on.

TR: A good DCP would allow you so much more freedom to screen the film in modern venues.

SH: Right. So we’re in the final phase of that restoration project. I think the film is very unique. There’s no other like it.

TR: What about other projects you’re working on together, beyond Starchaser?

JS: We’re in the development stage on two 3D animated features. One’s a Christmas movie about a young boy who ends up becoming Santa for a day. And the other is a teen romantic superhero story. We have half the financing in place, and are just trying to close the co-financing on it, and then get into production. I wrote both screenplays.

TR: I imagine after Starchaser, and all the lessons you learned on it, these new 3D productions would have to be a lot smoother.

JS: There’s no question about that!

TR: It’s been thirty years since Starchaser premiered. Looking back on the film now, what’s your overall memory of the project?

SH: I’d like to answer that in a different way. I learned two things on Starchaser. One, never spend your own money! (laughs) That’s important. And two, pioneers don’t always get the full fruit of their labor. By that I mean, if you go into the Amazon, it’s so difficult to carve your own path through the jungle. But then, the next person who comes that way just drives right through! You work hard to clear away the bushes and everything, and then the others just follow the road you created. And that’s what we did with Starchaser. We cleared a path for the future.

Previously by Matthew Chernov

10 Secrets From the Cast & Crew of the ’80s Rambo Cartoon

10 Revelations From the New ‘He-Man’ Soundtrack Producers

10 Things We Learned From the 1986 Transformers Movie’s Original Cast & Crew